Surayya, an HCV survivor, at Islamabad’s Civil Dispensary. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan 3 August 2025, Islamabad, Pakistan – “Hepatitis C is a deadly disease; everyone should get tested,” says Safina Saqib, a hepatitis C patient now fully recovered. She is one of the 30 000 patients from slum areas of Islamabad Capital Territory who have been tested, following protocols and guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO), at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary over the last 5 years.

Surayya, an HCV survivor, at Islamabad’s Civil Dispensary. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan 3 August 2025, Islamabad, Pakistan – “Hepatitis C is a deadly disease; everyone should get tested,” says Safina Saqib, a hepatitis C patient now fully recovered. She is one of the 30 000 patients from slum areas of Islamabad Capital Territory who have been tested, following protocols and guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO), at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary over the last 5 years.

Safina Saqib on her follow up visit to the Federal Government Civil dispensary after her recovery from hepatitis. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan Pakistan carries the heaviest burden of hepatitis C (HCV) globally, with 10 million cases out of 50 million globally. Every 20 minutes, someone in Pakistan dies due to HCV-related complications. Only 25–30% of those affected are aware of it, meaning the vast majority neither seek nor receive lifesaving treatment.

Safina Saqib on her follow up visit to the Federal Government Civil dispensary after her recovery from hepatitis. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan Pakistan carries the heaviest burden of hepatitis C (HCV) globally, with 10 million cases out of 50 million globally. Every 20 minutes, someone in Pakistan dies due to HCV-related complications. Only 25–30% of those affected are aware of it, meaning the vast majority neither seek nor receive lifesaving treatment.

WHO is partnering with Pakistan's Ministry of National Health Services and provincial health departments to strengthen hepatitis testing, screening, prevention and treatment protocols. The Organization is also supporting the National Hepatitis Strategic Framework and provincial hepatitis action plans, micro-elimination initiatives and biomarker surveys.

Hepatitis C is preventable and can be cured. However, if left untreated, it can lead to medical complications – including liver cancer – and death.

In Pakistan, the most common modes of transmission are unsafe procedures and materials used during blood transfusions – often due to unregulated private blood banks and a lack of universal screening, injections with re-used and non-sterile syringes and needles, surgical procedures, dental care, body piercing, tattooing and shaving – including at barber shops.

“For the prevention of this disease, consulting a doctor and receiving treatment is mandatory,” says Emanuel Masih, a hepatitis C survivor who urges others to seek medical attention, diagnosis and treatment.

Surayya, wife of Emanuel Masih and a hepatitis C survivor, also shared her story of recovery and how she is spreading awareness in her community. “I had hepatitis C and was worried because I couldn’t walk due to pain. Then I got treated at the facility and now I am doing well. Now, I tell everyone in my neighbourhood to get tested and treated.”

Safdar Masih, HCV survivor, at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary, Islamabad. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan To support patients like Emanuel and Surayya, WHO is providing technical support to the Prime Minister’s National Programme for the Elimination of Hepatitis C Infection, which aims to test 50% of the eligible population (82.5 million people aged 12 years and above) and treat 5 million people by 2027. “We must unite to spread the message that eliminating hepatitis C is important for the prosperity of our country and its people,” says Safdar Masih, who recovered from the disease one year ago.

Safdar Masih, HCV survivor, at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary, Islamabad. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan To support patients like Emanuel and Surayya, WHO is providing technical support to the Prime Minister’s National Programme for the Elimination of Hepatitis C Infection, which aims to test 50% of the eligible population (82.5 million people aged 12 years and above) and treat 5 million people by 2027. “We must unite to spread the message that eliminating hepatitis C is important for the prosperity of our country and its people,” says Safdar Masih, who recovered from the disease one year ago.

Stories like those of Safdar, Safina and Surayya reflect a renewed sense of hope and determination to fight a silent killer that disproportionally affects the most vulnerable communities in Pakistan. The goal: ending hepatitis as a public health problem by 2030.

Staff member at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary performs a rapid medical test for hepatitis. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan

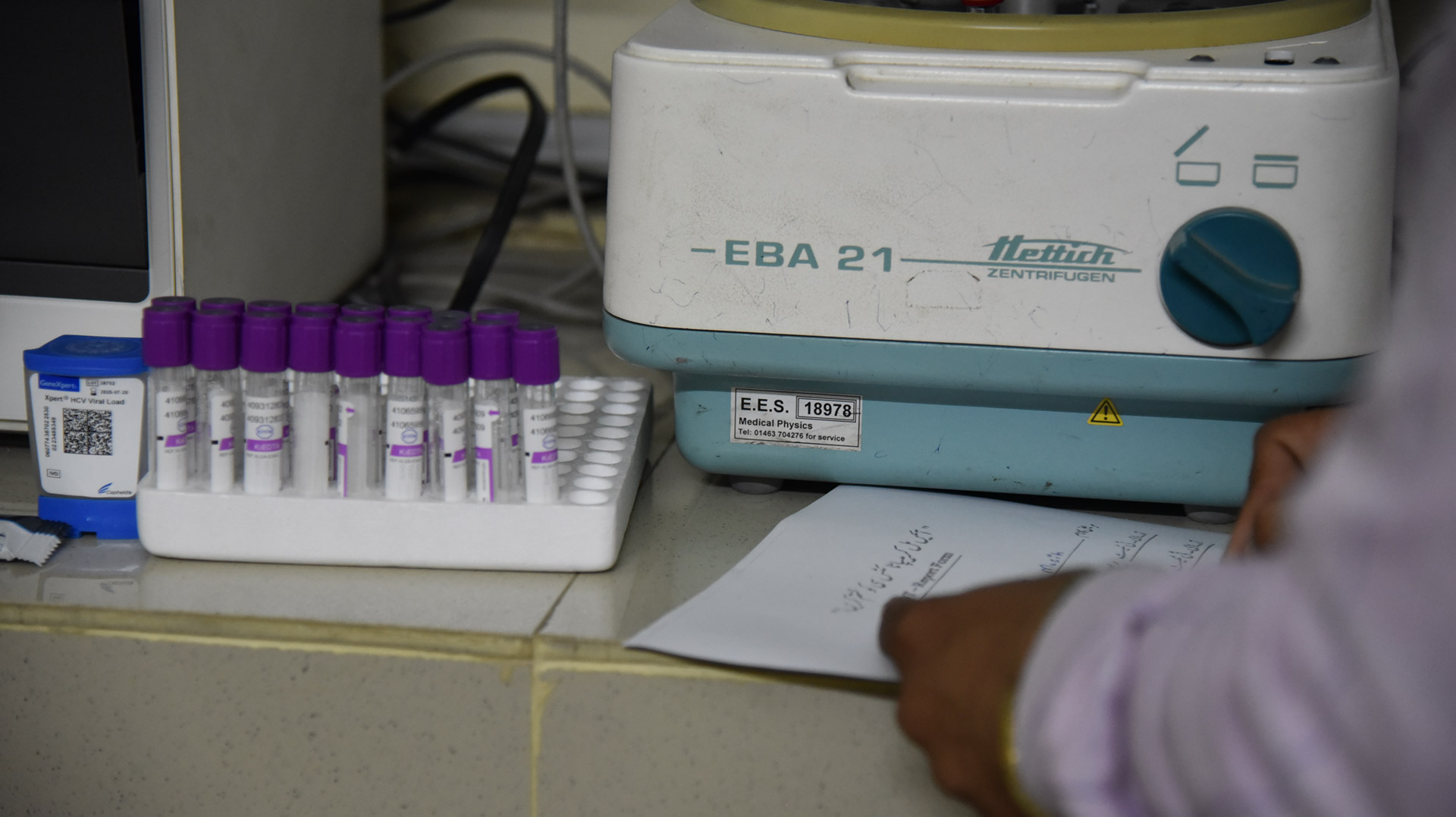

Staff member at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary performs a rapid medical test for hepatitis. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan  A specialist works at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary laboratory in Islamabad. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan

A specialist works at the Federal Government Civil Dispensary laboratory in Islamabad. Photo credit: Sara Akmal/WHO Pakistan Written by Sara Akmal

Edited by José Ignacio Martín Galán