N.S. Al-Sareai,1 Y.M. Al-Khaldi,1 O.A. Mostafa 2 and M.M. Abdel-Fattah 3

جسامة الإنهاك وعوامل اختطار الإصابة به لدى أطباء الرعاية الصحية الأولية في إمارة عسير في المملكة العربية السعودية

ناصرسعيد السريعي، يحي ماطر الخالدي، أسامة أحمد مصطفى، معتز محمد عبد الفتاح

الخلاصـة: يُعَدُّ الإنهاك المتعلق بالعمل من المخاطر المهنية التي يتعرض لها المهنيون في الرعاية الصحية. وتهدف هذه الدراسة إلى معرفة معدل انتشار الإنهاك والعوامل المرافقة له لدى الأطباء الذين يعملون في مراكز الرعاية الصحية في إمارة عسير في المملكة العربية السعودية، وهي دراسة مسحية مستعرضة طبَّقت استبيان مسلاش للإنهاك ذا الفياصل (الحدود الفاصلة) المعيارية. وتبين للباحثين أن %29.5 من المستجيبين قد أبلغوا عن نضوب عاطفي شديد، وأن %15.7 قد أبلغوا عن تبدُّد شديد في الشخصية وأن %19.7 قد أبلغوا عن إنجاز شخصي منخفض، وأن %6.3 قد حازوا أحرازاً عالية في الأبعاد الثلاثة جميعها. وقد ترابط النضوب العاطفي الشديد مع العمر الأقل، ومع الجنسية السعودية، ومع الرواتب التي تتراوح بين

000 15 و000 20 ريال سعودي. وكان الأطباء الذين يعملون في عدد أكبر من الأيام، والذين يقضون فترة أطول في الإجازات، أقل من غيرهم في احتمال الإبلاغ عن النضوب العاطفي. أما أحراز التبدد الشديد في الشخصية فقد ترابَطَتْ مع الجنسية السعودية، ومع العمل لمدة تتراوح بين 5 و15 عاماً، وبراتب يزيد على 000 20 ريال سعودي. ثم إن أحراز الإنجاز الشخصي المنخفضة قد ترابَطَتْ مع العمر المنخفض، والجنسية غير السعودية، والعمل لفترة تعادل أو تفوق خمس سنوات، وبالمزيد من الإجازات السنوية.

ABSTRACT Job-related burnout is an occupational hazard for health care professionals. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of burnout and its associated factors among physicians working at primary health care centres in Asir province, Saudi Arabia. In a cross-sectional survey applying the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) with standard cut-offs, 29.5% of respondents reported high emotional exhaustion, 15.7% high depersonalization and 19.7% low personal accomplishment, with 6.3% scoring high in all 3 dimensions. High emotional exhaustion score was associated with younger age, Saudi nationality and salary 15 000–20 000 SR. Physicians who had more working days and those who had longer duration of annual vacation were less likely to report emotional exhaustion. High depersonalization score was associated with Saudi nationality, working for 5–15 years and salary > 20 000 SR. Low personal accomplishment score was associated with younger age, non-Saudi nationality, working for ≥ 5 years and more annual vacation.

Ampleur et facteurs de risque du syndrome d'épuisement professionnel chez des médecins de soins de santé primaires dans la province d'Asir (Arabie saoudite)

RÉSUMÉ Le syndorme d'épuisement professionnel est un risque pour le personnel de santé. La présente étude visait à déterminer la prévalence de l'épuisement et des facteurs associés chez des médecins travaillant dans des centres de soins de santé primaires de la province d'Asir (Arabie saoudite). Dans une étude transversale utilisant l’inventaire d’épuisement professionnel de Maslach avec des seuils normalisés, 29,5 % des répondants ont déclaré éprouver un épuisement psychologique important, 15,7 % une forte dépersonnalisation et 19,7 % un faible accomplissement personnel. Au total, 6,3 % des médecins ont obtenu des résultats élevés pour ces trois aspects. Un score élevé pour l'épuisement était associé à un âge plus jeune, la nationalité saoudienne et un salaire compris entre 15 000 et 20 000 riyals saoudiens. Les médecins qui travaillaient pendant un plus grand nombre de jours dans la semaine et ceux qui avaient pris des congés annuels plus longs présentaient moins de risque. Avoir la nationalité saoudienne, être en activité depuis 5 à 15 ans et toucher un salaire supérieur à 20 000 riyals saoudiens étaient associés à un résultat élevé pour la dépersonnalisation. Un faible score pour l'accomplissement personnel était associé au fait d'être plus jeune, de ne pas avoir la nationalité saoudienne et d'avoir eu une durée d'activité supérieure ou égale à 5 ans et des congés annuels plus longs.

1Joint Programme of Family Medicine, Asir, Saudi Arabia;

2Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia.

3Research Unit, Al-Hada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia (Correspondence to M. Abdel-Fattah:

Received: 22/01/12; accepted: 11/04/12

EMHJ, 2013, 19(5):426-434

Introduction

The term “burnout”, originally used for engine malfunction, was first applied to humans in the mid-1970s to describe a stress syndrome with reported symptoms including exhaustion, frustration, anger, carelessness and a feeling of ineffectiveness and/or failure [1]. Occupational burnout varies greatly in the presentation and severity of its manifestations [2]. An important element of the syndrome is a negative impact on job performance for professionals involved in people-oriented services, especially health care professionals [2–5]. It has been described as a state of physical and emotional exhaustion with a poor self-image, a negative attitude towards work and loss of concern or interest in patients [5]. Exhaustion from too much work or dissipation results in negative attitudes toward both others and oneself [6]. Emotional exhaustion is a chronic state of physical and emotional depletion that results from excessive job demands and continuous stress. Depersonalization is another component of the syndrome and is an anomaly of the mechanism by which an individual has self-awareness; it is a feeling of watching oneself act, while having no control over a situation [7].

The syndrome tends to occur in people who have excessive expectations of themselves and who feel they need to do everything right [8]. Symptoms of burnout were found to be significantly associated with a perception of stressful and unrewarding working conditions, as well as with a variety of other negative behaviours including lateness, absenteeism, use of tranquilizing drugs, physical illness and withdrawal from others [9]. The practical symptoms of job dissatisfaction are usually interpreted as mistakes at work, accident proneness and absenteeism [10].

Burnout has implications for the employing organization through absenteeism, staff conflict and high staff turnover, which lead to both short and long-term manpower instability, resulting in further stress. It is therefore important to examine the causes of burnout in order to determine coping strategies that may be followed to manage it [11]. The present study aimed to investigate the magnitude and risk factors of burnout among physicians working at the primary health care level in Asir province, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Study design and sample

A cross-sectional study was carried out from October 2010 to June 2011 in Asir province in Saudi Arabia. The province is located in the south-west of the country and has an area of 81 000 km² and an estimated population of 1 913 392. All physicians working at government primary health care centres (PHCCs) in Asir province were invited to participate in the current study. At the time of the study there were 235 government PHCC and 390 physicians working at these centres [12].

Data collection

After being given assurances of full confidentiality and anonymity of the data, physicians answered a self-administered questionnaire which included the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) as well as data on their demographic and professional characteristics (i.e. age, sex, nationality, salary, qualification, specialty, years of experience after qualification, duration of work at the health facility and number of working days per week).

The MBI has been found to be reliable, valid [13] and easy to administer. It is designed to assess the 3 components of the burnout syndrome—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment—using 22 items which are divided into the 3 subscales. The items are answered in terms of the frequency with which the respondent experiences these feelings, on a 7-point (from 0 “never” to 6 “every day”) [14]. The 9 items in the emotional exhaustion subscale (statements 1–9) assess feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s work. The 5 items in the depersonalization subscale (statements 10–14) measure an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one’s service, care, treatment or instruction. For both the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales, higher mean scores correspond to higher degrees of experienced burnout. The 8 items in the personal accomplishment subscale (statements 15–22) assess feelings of competence and successful achievement in one’s work with people. In contrast to the other 2 subscales, lower mean scores on this subscale correspond to higher degrees of experienced burnout [14]. The scores for each subscale are considered separately and are not combined into a single, total score, thus, 3 scores are computed for each respondent. If desired for individual feedback, each score can then be coded as low, average or high by using the numerical cut-off points listed on the scoring key [14]. We used the cut-off scores of ≥ 26 for high emotional exhaustion, ≥ 9 for high depersonalization and ≤ 33 for diminished personal accomplishment [15].

In the current study, the MBI was found to be a reliable instrument with sufficient coefficients of internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.74 for emotional exhaustion, α = 0.69 for depersonalization and α = 0.71 for personal accomplishment subscales).

Data management and statistical analysis

The collected data was analysed using SPSS, version 18.0. Percentages, mean and standard deviation (SD) were used as descriptive statistics. Bivariate analysis of mean burnout subscale scores with regard to independent variables were done by unpaired t-test (for comparison of the means of 2 groups) and ANOVA (for comparison of the means of more than 2 groups). Least significance difference test was used for post hoc comparisons of ANOVA (results are not included in the article). Variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment on the MBI scale were treated as the dependent variable in multivariate logistic regression analysis. The independent variables were: the demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, nationality, qualifications and salary) and professional characteristics (professional status, years of profession, specialty, duration of work in the current facility, number of working days per week, number and duration of annual vacations in weeks). Three multivariate logistic regression models were created, 1 for each subscale of the MBI scale.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Out of 390 questionnaires distributed to eligible physicians, 370 were returned, giving a response rate of 94.9%. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of physicians. Their age ranged between 26–60 years with a mean of 39.8 (SD 8. 9) years. More than half of them (54.6%) were aged < 40 years. The majority were males (81.9%) and married (91.1%). Saudi Arabian nationality physicians were 15.7%. The majority of respondents (86.8%) had an MB BCh qualification, while only 0.6% also had an MD qualification or Fellowship. The great majority (84.6%) had a monthly salary of < 10 000 Saudi riyals (SR) and 1.1% a salary of > 20 000 SR.

Professional characteristics

Table 2 presents the professional characteristics of the physicians. The great majority of them (98.1%) were residents and only 0.5% were consultants. Work experience ≤ 5 years was reported by 17.3% of the participants, while experience > 15 years was reported by 33.2%. Approximately 42.4% of physicians mentioned that they spent ≥ 5 years in their current PHCC. Most of the respondents were general practitioners (77.0%) and 17.3% were family physicians. Almost two-thirds of the physicians claimed that they had 5 working days/week (64.1%). Most of the physicians had between 5–7 weeks as an annual vacation (86.8%).

Prevalence of burnout

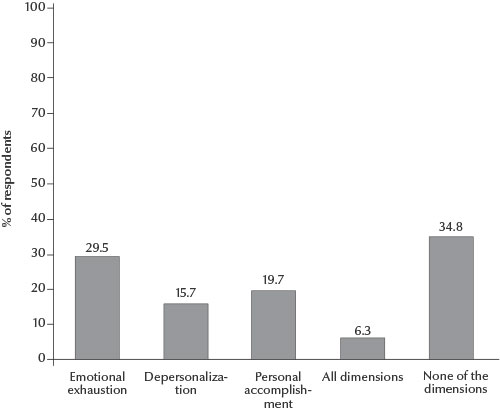

As shown from Figure 1 , 29.5% of the respondents had a high level of emotional exhaustion, 15.7% had a high level of depersonalization and 19.7% had a low level of personal accomplishment. Overall, 24 physicians (6.3%) scored high on burnout in all 3 dimensions. In addition, slightly over one-third of physicians (34.8%) had no burnout in any dimension.

Figure 1 Prevalence of burnout on subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians working at primary health care centres in Asir province, Saudi Arabia

Risk factors for burnout

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis for risk factors for emotional exhaustion are presented in Table 3. Older physicians were less likely to report emotional exhaustion than young physicians. Saudi nationality physicians had a 4-fold greater risk for emotional exhaustion compared with non-Saudi physicians (OR = 4.14; 95% CI: 1.66–9.75). Physicians who had more working days per week and those who had longer duration of annual vacation were less likely to report emotional exhaustion. Physicians who had salary between 15 000–20 000 SR were more likely to have high scores on emotional exhaustion than those who had salary < 10 000 SR.

The risk factors of depersonalization are presented in Table 4. Non-Saudi physicians were less likely to have high scores on depersonalization than Saudi physicians. Physicians who worked for a period between 5–15 years had an approximately 5-fold risk for depersonalization as compared to those who worked for < 5 years (OR = 4.96; 95% CI: 1.86–16.9). Physicians who had a monthly salary > 20 000 SR were less likely to report depersonalization as opposed to those who had salary < 10 000 SR.

The risk factors for low personal accomplishment are presented in Table 5. Physicians aged 40–49 years were less likely to have low scores on personal accomplishment than those who were ≤ 29 years. Non-Saudi physicians were more likely to have low personal accomplishment scores than Saudi nationals. Similarly, those who worked in their current PHCC for ≥ 5 years were more likely to feel a low level of personal accomplishment than who worked for < 5 years. Physicians with a longer duration of annual vacation were more likely to report a low level of personal accomplishment than those with a shorter duration of annual vacation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional survey to determine the prevalence and predictors of burnout among PHC physicians in Asir province, Saudi Arabia. Using the MBI we found that 6.3% of the respondents scored high burnout in all 3 dimensions, with 29.5% having a high level of emotional exhaustion, 15.7% a high level of depersonalization and 19.7% a low level of personal accomplishment. Though burnout rates can change depending on the organizational context and specific samples, many studies report high levels of burnout in doctors, with the prevalence of psychological morbidity (i.e. scores on all 3 subscales) ranging from 19% to 47%, compared with a rate around 18% for the general employed population [16]. Studies in Western European countries, including Switzerland, Italy and France, reported prevalences ranging from around 20% to more than 50% in some studies [17]. The data in the literature provide no consistent picture about which medical specialty has the highest rate of burnout. The reported prevalence in the different disciplines varies, but one study found rates ranging from 27% in family medicine to 75% in obstetrics/gynaecology [18]. For primary care doctors or general practitioners, a moderate to high degree of burnout was reported for one-third of them [19].

In Japan, a study of burnout among physicians engaged in end of-life care for cancer patients found that 22% of the respondents had a high level of emotional exhaustion, 11% had a high level of depersonalization and 62% had a low level of personal accomplishment [20]. The European General Practice Research Network Burnout Study Group (EGPRN) conducted research among family doctors in 12 European countries in 2006. The study showed that 43% of respondents had high scores for emotional exhaustion burnout, 35% high scores for depersonalization and 32% low scores for personal accomplishment, while 12% of physicians scored high burnout in all 3 dimensions [21]. In the current study, the proportion of physicians scoring high on individual and all 3 subscales were lower than that reported by the EGPRN study. In other studies of burnout in general physicians, high levels of emotional exhaustion (19%–53%), high levels of depersonalization (22%–64%) and low scores on personal accomplishment (13%–31%) were observed [22–32]. Again, our rates of burnout were relatively lower compared with those studies [21,32,33]. Most studies emphasize the interaction between personality and environmental factors as the most important cause of the development of burnout in medical practitioners [34].

Saudi Arabian nationals and physicians who had a monthly salary between 15 000–20 000 SR were more likely to report emotional exhaustion, and this could be related to their engagement in continuous postgraduate training. As seen in another study increased postgraduate requirements may lead to burnout [35]. Residents in our study had significantly higher scores on emotional exhaustion than specialists and consultants in bivariate analysis although this became insignificant in multiple logistic regression analysis. In one study non-specialists had higher burnout scores than specialists for both sexes [36]. Emotional exhaustion score was significantly higher in physicians who had qualifications in other specialties than that of general practitioners and family physicians.

Physicians who reported having more than 7 weeks of vacation annually had significantly lower scores for emotional exhaustion in our study, and this is similar to another study that found the most significant and common predictors of all burnout dimensions and job satisfaction were the number of vacations [36]. In accordance with our results, a study of transplant surgeons showed that less leisure time per month was the strongest predictor of emotional exhaustion [37]. Interestingly, older physicians and physicians who had more working days per week were significantly less likely to report emotional exhaustion. We might explain these findings by older doctors’ greater experience and familiarity with the system and/or patients or because many of them were about to retire. Also they may have been more likely to be working at rural areas where there is lower daily workload and less demanding patients.

The personal accomplishment score was significantly lower in physicians of Saudi Arabian nationality than in non-Saudi physicians. Low personal accomplishment is usually accompanied by high scores on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. In the bivariate analysis personal accomplishment score was significantly higher in specialists than consultants and residents, presumably because they were more recently graduated. However, this variable was not significant in the multivariate analysis. The personal accomplishment score was significantly higher among physicians aged ≥ 50 years, and those working > 5 years in the current PHCC. Surprisingly those working for 6 days/week had significant higher personal accomplishment scores than those working 5 days/week and again we can explain these findings by older physicians’ greater experience, being close to retirement and having rural practices. Physicians whose salary was > 20 000 SR/month and who had > 7 weeks of vacation annually had significantly higher score for personal accomplishment. In a large-scale survey of oncologists, the majority of respondents indicated the need for more vacation or personal time to alleviate burnout [38].

In the current study high depersonalization was reported among 15.7% of physicians. This rate is lower than that reported in another Saudi study conducted among orthopaedic surgeons (59.4%) [39]. The difference could be attributed to the difference in the quality of participants in the 2 studies. DP was significantly higher among physicians who practising for a longer duration, while it was significantly lower among non-Saudi physicians and those with high incomes. In a study conducted in Kuwait, general practitioners had high depersonalization (65.3%) compared with family physicians (27.6%) [40]. However, in the present study, the specialty of physicians was not a significant predictor or high depersonalization. Although it has been documented that female physicians report lower scores of depersonalization than do males [41], we did not show this in the present study.

An important limitation of our study was its cross-sectional nature and data collection method, which creates difficulties in ascertaining causality. The use of self-reported data collected at one point in time requires care in drawing conclusions about the effects of working conditions on burnout. However, we believe that the results of this study will improve our understanding of the psychosocial work climate of PHC physicians in Asir province. Production and sharing of scientific information on these issues is important and useful: many countries in Eastern Europe, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Central Asia, South America and even some developed countries, have been trying to transform their health care system and implement health care reforms in recent years [42].

Based on the results of this study, we can conclude that, generally, burnout is not uncommon among physicians working at PHCCs in Asir province, Saudi Arabia. Burnout was associated with a number of sociodemographic and professional determinants. We recommend the development of periodic (annually/with recruitment) screening systems to recognize early signs of impairment and distress of PHC physicians using the MBI questionnaire, as well practical strategies for avoiding burnout.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- Felton JS. Burnout as a clinical entity—its importance in health care workers. Occupational Medicine, 1998, 48:237–250.

- Allen J, Mellor D. Work context, personal control, and burnout amongst nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 2002, 24:905–917.

- Soler JK et al. Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Family Practice, 2008, 25:245–265.

- Lee I, Wang HH. Perceived occupational stress and related factors in public health nurses. Journal of Nursing Research, 2002, 10:253–260.

- Cilliers F. Burnout and salutogenic functioning of nurses. Curationis, 2003, 26:62–74.

- Azab HM, Mostafa OA, El-Sayed SH. Risk factors for work-related stress, burnout and coping among nurses of university hospitals. Medical Journal of Cairo University, 2006, 74:189–195.

- Hoffman AJ, Scott LD. Role stress and career satisfaction among registered nurses by work shift patterns. Journal of Nursing Administration, 2003, 33:337–342.

- Balevre P. Professional nursing burnout and irrational thinking. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 2001, 17:264–271.

- Kalliath T, Morris R. Job satisfaction among nurses: a predictor of burnout levels. Journal of Nursing Administration, 2002, 32:648–654.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Additional conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. Volume 2, behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2004:894–900.

- Brinkman A. Occupational stress in hospitals—a nursing perspective. Nursing New Zealand, 2002, 8:21–23.

- Primary health care: annual report. Abha, Saudi Arabia, Directorate General of Health Affairs, Asir province, 2010 [1431H].

- Rafferty JP et al. Validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for family practice physicians. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1986, 42:488–492.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 1981, 2:99–113.

- Truzzi A et al. Burnout in a sample of Alzheimer’s disease caregivers in Brazil. European Journal of Psychiatry, 2008, 22:151–160.

- Firth-Cohen J. New stressors, new remedies. Occupational Medicine, 2006, 50:199–201.

- Deckard G, Meterko M, Field D. Physician burnout: an examination of personal, professional, and organizational relationships. Medical Care, 1994, 32:745–754.

- Martini S, Arfken CL. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Academic Psychiatry, 2004, 28:240–242.

- Goehring C et al . Psychological and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional survey. Swiss Medical Weekly, 2005, 135:101–108.

- Asai M et al. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among physicians engaged in end-of-life care for cancer patients: A cross-sectional nationwide survey in Japan. Psycho-Oncology, 2007, 16:421–428.

- Soler JK et al. Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Family Practice, 2008, 25:245–265

- Graham J, Potts HW, Ramirez AJ. Stress and burnout in doctors. Lancet, 2002, 360:1975–1976.

- Smets EMA, Visser MRM, Oort FJ. Perceived inequity: Does it explain burnout among medical specialist? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2004, 34:1900–1918

- Kluger MT, Townend K, Laidlaw T. Job satisfaction, Stress and burnout in Australian specialist anaesthetists. Anaesthesia, 2003, 58:339–345

- Gundersen L. Physician burnout. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2001, 135:145–148.

- Thommasen HV et al. Mental health, job satisfaction and intention to relocate. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 2001, B47:737–744.

- Goehring C et al. Psychological and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional survey. Swiss Medical Weekly, 2005, 135:101–108.

- Truzzi A et al. Burnout in a sample of Alzheimer’s disease caregivers in Brazil. European Journal of Psychiatry, 2008, 22:151–160.

- Firth-Cohen J. New stressors, new remedies. Occupational Medicine, 2006, 50:199–201.

- Deckard G, Meterko M, Field D. Physician burnout: an examination of personal, professional, and organizational relationships. Medical Care, 1994, 32:745–754.

- Martini S, Arfken CL. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Academic Psychiatry, 2004, 28:240–242.

- Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2002, 136:358–367.

- Grassi L, Magnani K. Psychiatric morbidity and burnout in the medical profession: an Italian study of general practitioners and hospital physicians. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 2000, 69:329–334

- Potier G. Burnout in the medical profession: Causes, consequences and solutions. Occupational Health at Work, 2007, 3:134–140.

- Visser MRM et al. Stress satisfaction and burnout among Dutch medical specialist. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 2003, 168:271–275.

- Olkinuora M et al. Stress symptoms, burnout and suicidal thoughts in Finnish physicians. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 1990, 25:81–86.

- Ozyurt A, Hayran O, Sur H. Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians. Quarterly Journal of Medicine, 2006, 99:161–169.

- W hippen DA, Canellos GP. Burnout syndrome in the practice of oncology: results of a random survey of 1000 oncologists. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1991, 9:1916–1921.

- Sadat AM et al. Are orthopedic surgeons prone to burnout? Saudi Medical Journal, 2005, 26(8):1180–1182.

- Al-Shoraian GMJ et al. Burnout among family and general practitioners. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 2011, 47:359–364.

- Grassi L, Magnani K. Psychiatric morbidity and burnout in the medical profession: an Italian study of general practitioners and hospital physicians. Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, 2000, 69:329–334.

- Riley GJ. Understanding the stresses and strains of being a doctor. Medical Journal of Australia, 2004, 181:350–353.