A.H. Al-Nakash1 and D.K. Al-Rahal2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Al-Kindy Medical College, Al-Elweya Maternity Teaching Hospital; 2College of Medicine, Baghdad University, Baghdad, Iraq (Correspondence to A.H Al-Nakash:

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

).

Received: 04/08/04; accepted: 20/12/04

EMHJ, 2006, 12(3-4): 489-491

Introduction

Schistosoma haematobium is endemic in Iraq, constituting an important health problem in this country [1,2]. Boulanger in 1919 reported the geographical distribution of schistosomiasis in Mesopotamia [2]. More recent reports suggest that the reported incidence of schistosomiasis in the Iraqi adult population is 4.9% [3], and the incidence in autopsy materials in the Medical City Teaching Hospital in Baghdad is 4.4% [4].

Although S. haematobium usually affects the urinary system, involvement of the genital organs is not unusual in endemic zones, occurring via the vascular anastomosis between the bladder and the genital organs [5]. Aberrant nidation, spontaneous abortion and permanent sterility were the most reported complications of the genital schistosomiasis. It is also responsible for functional sequelae including pelvic ache and menstrual problems [6]. Other bilharzial species have also been blamed for genital organ diseases in the areas where they are endemic, producing comparable symptoms [7,8].

We report a case of bilharzial infection of a uterine leiomyoma with other genital organs unaffected.

Case report

A 34-year-old grand multiparous woman from Baladros, north-east Baghdad, presented with a lower abdominal mass that had been present for the last 2 years.

Her menstrual cycle was regular, but recently she noticed that her menstrual flow became heavier and associated with symptoms of congestive dysmenorrhea and deep dyspareunia. She had no urinary complaints and no previous history of haematuria.

Abdominal examination revealed a firm, smooth and partly fixed central pelvic abdominal mass of about 16 weeks gestation size. It was tender on deep palpation. There were no other physical findings. Pelvic examination showed an apparently normal vagina and cervix. On bimanual examination a firm mass was felt, involving the uterus and limiting its movement. Ultrasound showed an anterofundal uterine myoma of about 11×11 cm. Her other organs were normal.

Her husband and her 4 sons complained of urinary schistosomiasis and were on treatment, while her 4 daughters were symptom-free. In her district of Baghdad, schistosomiasis is endemic. However, blood tests on the woman were normal and repeated urinary analysis (3 times) showed no bilharzial ova.

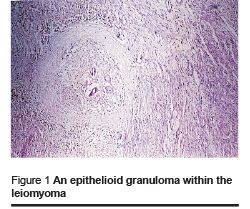

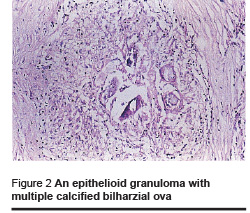

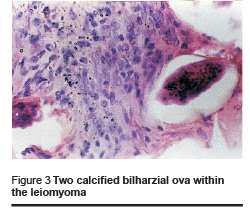

Total abdominal hysterectomy was performed (with the patient’s agreement) leaving ovaries of normal appearance. The specimen showed a uterus with distorted shape and two fallopian tubes, measuring 11×12×16 cm at the widest diameter. Sectioning showed a nodular mass measuring about 11 cm in diameter involving the antero-fundal area of the uterus, whitish-grey in colour, with a firm whorled cut section. Microscopically, the benign leiomyoma showed multiple epitheloid granulomas with calcified bilharzial ova within the leiomyoma. No bilharzial lesions were present in other parts of the specimen (Figures 1–3).

Discussion

The human is not the final host for the schistosome. It is the extreme inflammatory response to eggs deposited in the soft tissues that gives rise to chronic presentations of schistosomiasis [9,10]. Some of the eggs become calcified rather than resorbed and are generally surrounded by dense fibrosis which, as in our case, be seen long after the original infection.

This case of bilharzial infection of a uterine myoma surprisingly spared other genital organs. We cannot offer a clear explanation for this occurrence; fibroid tissue is known to be less vascular than other uterine parts, and it seems that certain vascular connections had played a role in this situation. The resultant granulomatous inflammation had possibly influenced the size of the fibroid, explaining its relatively large size in this patient.

Tawfikh et al. [2] reported on genital bilharziasis in Iraq, demonstrating distribution of the disease in the genital organs. The fallopian tube was the commonest site of involvement (71.2%), followed by the cervix (13.5%) and the ovary (9.6%). Uterine, vulval and vaginal involvements were less frequent. Infertility was the commonest presentation (38.5%) and the rate of ectopic pregnancy was 8%. These figures are not consistent with that given by Gouzouv et al. [6] who recorded the involvement of genital organs as follows: cervix (42%), ovary (21%), fallopian tube (16%) and vulva, vagina and clitoris (21%).

Unlike the other members of her family, our patient was free from the urinary manifestations of schistosomiasis, and her fertility was not affected. No anti-bilharzial treatment was given because it was evident that that the original infection had halted long before.

References

- Boulanger GL. Report on bilharziasis in Mesopotamia. Indian journal of medical research, 1919, (7):8.

- Tawfikh LE, Al-Wafa RO, Mukhlis GM. Schistosomiasis of the female genital tract in Iraq. Iraqi journal of community medicine, 1995, 1:37–42.

- Report of investigation of endemic disease. Baghdad, Iraq, Ministry of Health 1982.

- Al-Saleem T, Alsh N, Tawfikh LE. Bladder cancer in Iraq: the histological subtypes and their relationship to schistosomiasis. Annals of Saudi medicine, 1990, 10:161–4.

- Morice P et al. Bilharzoise tubaire. [Tubal bilharziasis.] Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction, 1993, 22(8):848–50.

- Gouzouv A, Baldassini B, Opa JF. Aspect anatomo-pathologique de la bilharziose genitale de la femme. [Anatomicopathological aspects of genital bilharziasis in women.] Medecine tropicale: revue du Corps de sante colonial, 1984, 44(4):331–7.

- Richard-Lenoble D et al. Bilharziose a Schistosoma intercalatum bilharziose recente et oubliee. [Bilharziasis caused by Schistosoma intercalatum, a recent and forgotten form of schistosomiasis.] La Revue du praticien, 1993, 43(4):432–9.

- Billy-Brissac R et al. Bilharziose genitale de la femme a Schistosoma mansoni: a propos de deux cas en Guadeloupe. [Genital Schistosoma mansoni bilharziasis in women: apropos of 2 cases in Guadeloupe.] Medecine tropicale: revue du Corps de sante colonial, 1994, 54(4):345–8.

- Helling-Giese G et al. Schistosomiasis in women: manifestations in the upper reproductive tract. Acta tropica, 1996, 62(4):225–38.

- Ricosse JH, Emeric R, Courbil LJ. Aspects anatomo-pathologiques des bilharzioses (a propos de 286 pieces histopathologiques). [Anatomopathological aspects of schistosomiasis. A study of 286 pathological specimens.] Medecine tropicale: revue du Corps de sante colonial, 1980, 40(1):77–94.

Volume 31, number 5 May 2025

Volume 31, number 5 May 2025 WHO Bulletin

WHO Bulletin Pan American Journal of Public Health

Pan American Journal of Public Health The WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health (WHO SEAJPH)

The WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health (WHO SEAJPH)