|

Advocacy materials |

|

|

|

Communicable diseases |

|

|

Poliomyelitis eradication

Outbreaks of poliomyelitis occurred in the Syrian Arab Republic and Somalia. These were a serious blow to the progress of the global polio eradication programme and a threat to all countries. Indeed, the outbreak in Somalia, the result of importation from Nigeria, also affected neighbouring Kenya and Uganda. In response, the Regional Committee adopted a resolution on intensifying polio eradication efforts in the Region declaring the spread of wild poliovirus an emergency for all Member States of the Region and re-emphasizing the critical importance of stopping ongoing transmission of poliomyelitis in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In line with the resolution, comprehensive strategic plans were developed in coordination with national governments and partners to control the outbreaks. Multi-country outbreak responses were reviewed and phase II response plans developed, based on the evolving epidemiology and lessons learned.

In Somalia and Syrian Arab Republic a number of strategies were deployed to raise immediate population immunity and control the outbreaks, including use of the bivalent vaccine, short interval additional dose, permanent posts for vaccination in border transit areas, low profile vaccination teams, prepositioning of vaccine and expanding the age group for vaccination. The strong working partnership among all the partners was important in addressing the emerging issues and evolving epidemiological developments. Coordination between the WHO regional offices for Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean also had a positive impact in controlling the outbreak. Preventive vaccination campaigns were conducted in countries at particular risk, including Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine and Yemen, with special focus on refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons.

With regard to the two countries where poliovirus circulation continues, significant progress was made in Afghanistan, where transmission is well controlled in the southern endemic part of the country. Only one case was reported from the endemic area of the southern region. Other cases reported were from the eastern region, and genetic sequencing demonstrated a strong link with polioviruses in Pakistan. The primary challenge remains the inability to maintain high oral poliovaccine (OPV) coverage in the eastern provinces, especially Kunar. In Pakistan the situation deteriorated, largely owing to conflict, continuing ban by militants on immunization, insecurity and the continued killing of the polio workers in the field. Polio continues primarily in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and the neighbouring province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; of 93 cases reported by Pakistan in 2013, 66 were from FATA. The 2014 military operation in North Waziristan Agency of FATA has resulted in huge population migration to the neighbouring districts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The programme is continuously monitoring this movement and vaccinating at transit points, in camps and in the host community.

WHO provided additional human resources support to Afghanistan, Pakistan and Somalia, and to the Syrian Arab Republic and neighbouring countries. All national polio laboratories were accredited and rehabilitation services continued to be supported in Pakistan for children affected by polio. The Regional Director undertook advocacy missions to infected areas and a high-level Islamic Advisory Group was established. Cross-border coordination and interregional collaboration were strengthened, several emergency consultations were held to align partner support, and additional direct financial support was provided.

HIV, tuberculosis, malaria and tropical diseases

The number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the Region in 2013 is estimated at 280 000, of whom 17 000 are children. With an estimated 42 000 new HIV infections in 2013, the growth of the epidemic by far outpaces improvements made in terms of access to HIV prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment services. Coverage with antiretroviral therapy remains the lowest in the world, reaching almost 20% of those in need. This is attributed to an accumulation of gaps and weaknesses in the current HIV control strategies and programmes. The biggest gap lies in the ability to create and meet demand for HIV testing services, which is the primary gateway for access to treatment. In order to close these gaps political commitment, service delivery approaches and the health system all need to be strengthened, while persistent stigma and discrimination, including in health care settings, need to be addressed urgently.

In 2013, WHO launched the regional initiative to end the HIV treatment crisis, which aims at reaching universal coverage of 80% with antiretroviral therapy by 2020. Its immediate objective is to mobilize urgent action to accelerate access to treatment. For this purpose, WHO developed a guide and tools intended to assist countries in analysing gaps and lost opportunities along the continuum of prevention, testing, care and treatment in order to identify actions that may result in accelerating access. This is known as the HIV test–treat–retain cascade analysis, and, so far, five countries have carried out the analysis. WHO and UNAIDS developed a joint advocacy document which highlights the main reasons for low coverage of treatment in the Region and recommends key strategies and actions required to accelerate the scale-up of diagnosis and treatment.

WHO also developed consolidated antiretroviral therapy guidelines and 15 countries have updated, or are in the process of updating, their HIV treatment guidelines accordingly. Training modules were developed on basic HIV knowledge and stigma reduction for health workers and tested in two countries. WHO continued its support to countries and civil society organizations in collecting and analysing strategic information, developing national strategic plans and implementing effective evidence-based HIV prevention activities among key populations at increased risk of HIV.

During 2012[1], over 430 000 cases of all forms of tuberculosis were notified in the Region. Case detection for all forms of tuberculosis and for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) continues to pose a major challenge in the Region, and globally, as does the slow pace of decline in incidence. The regional case detection rate for all forms was 63% in 2012 (62% in 2011). Twelve countries achieved or exceeded the 70% target for case detection rate. The treatment success rate for new cases remained at 88% for the fifth consecutive year, and 13 countries reached or exceeded the global target of 85%. WHO support to countries focused on ensuring quality in tuberculosis care through technical support, monitoring of country programme implementation, in-depth review missions and capacity-building.

The situation with regard to MDR-TB is a major concern. Of 18 000 estimated cases, only around 2300 were detected in 2012. Of these 1602 cases were put on treatment; the treatment success rate for MDR-TB cases is around 56%. Adequate scale-up of MDR-TB control is prevented by the need to strengthen health systems and the allocation of financial resources specifically to address this growing problem. WHO worked with 10 countries to develop plans for ambulatory care based on the MDR-TB planning tool kit.

Eight countries in the Region reported local malaria transmission in 2013. In 2012, the total number of parasitologically confirmed malaria cases exceeded 1.3 million, which represents only 10% of the estimated cases in the Region. The reported number of deaths attributed to malaria was 2307, 84% of which were in South Sudan and Sudan (Table 1)[2]. The need to strengthen diagnosis and surveillance systems continues to be a major challenge in the high-burden countries, especially Pakistan, Somalia and Sudan. There were some improvements in Afghanistan and Yemen, in particular the expansion of the malaria information system. A malaria outbreak in Djibouti highlighted the urgent need to strengthen programme capacity and to strengthen epidemic preparedness, particularly regarding availability of diagnostics, antimalarial medicine and vector control commodities, as well as trained staff.

Table 1. Reported malaria cases in countries with high malaria burden

|

Country

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

|

Total reported cases

|

Total confirmed

|

Total reported cases

|

Total confirmed

|

Total reported cases

|

Total confirmed

|

|

Afghanistan

|

482748

|

77549

|

391365

|

54840

|

319742

|

46114

|

|

Djibouti

|

232

|

NA

|

25

|

25

|

1674

|

1674

|

|

Pakistan

|

4065802

|

334589

|

4285449

|

290781

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Somalia

|

41167

|

3351

|

59709

|

18842

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

South Sudan

|

795784

|

112024

|

1125039

|

225371

|

|

|

|

Sudan

|

1246833

|

506806

|

1001571

|

526931

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Yemen

|

142147

|

90410

|

165678

|

109908

|

149451

|

102778

|

Two countries, Islamic Republic of Iran and Saudi Arabia, are successfully implementing a malaria elimination strategy, despite the challenges they face in the border areas with Pakistan and Yemen, respectively. Population movement from malaria-endemic to malaria-free countries is increasing, resulting in more imported malaria and raising the risk of reintroduction of local transmission or occurrence of limited outbreaks of local cases as reported in Oman and Tunisia (Table 2). With WHO support, six countries conducted joint in-depth programme reviews involving key stakeholders and partners.

Table 2. Parasitologically-confirmed cases in countries with no or sporadic transmission and countries with low malaria endemicity

|

Country

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

|

Bahrain

|

186

|

0

|

233

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Egypt

|

116

|

0

|

206

|

0

|

262

|

0

|

|

Iraq

|

11

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

|

Islamic Republic of Iran

|

3239

|

1710

|

1629

|

787

|

1387

|

NA

|

|

Jordan

|

58

|

0

|

117

|

0

|

56

|

0

|

|

Kuwait

|

476

|

0

|

358

|

0

|

291

|

0

|

|

Lebanon

|

83

|

NA

|

115

|

0

|

133

|

0

|

|

Libya

|

NA

|

NA

|

88

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Morocco

|

312

|

0

|

364

|

0

|

314

|

0

|

|

Palestine

|

NA

|

NA

|

0

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Oman

|

1531

|

13

|

2051

|

22

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Qatar

|

673

|

0

|

708

|

0

|

728

|

0

|

|

Saudi Arabia

|

2788

|

69

|

3406

|

82

|

2513

|

34

|

|

Syrian Arab Republic

|

48

|

0

|

42

|

0

|

22

|

0

|

|

Tunisia

|

67

|

0

|

70

|

0

|

68

|

4

|

|

United Arab Emirates

|

5242

|

0

|

5165

|

0

|

4380

|

0

|

Access to anti-malarial treatment, insecticides and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) is improving in all endemic countries. Almost 11 million LLINs were distributed during 2011 and 2012 in endemic countries. In Afghanistan, the operational coverage in targeted high transmission districts is expected to be above 70% and in Pakistan, the operational coverage in targeted areas was 41% at the end of 2013. Access to malaria confirmation, whether by microscopy or rapid diagnostic test, continues to be a major challenge, although there is encouraging progress in Afghanistan and Yemen.

The WHO/GEF/UNEP project on sustainable alternatives to DDT for vector control proceeded with success in Islamic Republic of Iran, Morocco, Sudan and Yemen. National capacity for integrated vector management was strengthened in several countries

Remarkable successes were seen in the area of neglected tropical diseases. The number of cases of guineaworm disease in South Sudan decreased by 78% in 2013 (121 cases), compared to 2012, although three cases were identified in Sudan (South Darfur State) after almost 10 years without cases. Preliminary surveys suggest the reintroduction of the parasite from South Sudan. With regard to lymphatic filariasis, verification of the elimination of transmission was completed in Yemen and in 80% of the former affected areas of Egypt. It is still hoped to achieve similar success in Sudan. The largest schistosomiasis control programme currently operating worldwide entered its third year in Yemen with a record number of interventions in 2013 as approximately 40 million praziquantel tablets were distributed to about 13 million people. An impact evaluation assessment, conducted in selected sentinel districts, showed that infection levels have fallen by more than half since the beginning of the project. It is hoped the programme will continue to operate successfully and to achieve its goals, as well as to provide a case-study for other programmes in the Region, such as in Sudan, and beyond.

In the last quarter of 2013, data on leishmaniasis in the Region covering the past 15 years, together with interactive maps and graphs, were made available on the WHO Regional Health Observatory. Several countries developed national guidelines for leishmaniasis control and case management. In order to assess the impact of the WHO technical guidelines on leishmania, an impact assessment project was started in Morocco.

Immunization and vaccines

The main challenge for immunization programmes in 2013 was political instability and insecurity, which affected the implementation of mobile and outreach activities in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen and seriously affected routine immunization in the Syrian Arab Republic. The need to strengthen managerial capacity and commitment to routine immunization in addition to competing priorities are a challenge in some countries. The availability of financial resources also needs to be assured for implementation of supplementary immunization activities for measles and tetanus, introduction of new vaccines in middle-income countries and co-financing in GAVI eligible countries, as well as activities related to improving vaccination coverage in countries with low performance.

Despite such challenges, achievement of the regional expected results for routine immunization stayed on track for the vast majority of the indicators in 2013. Fourteen countries in the Region have achieved the target of 90% routine DTP3 vaccination coverage andYemen is close to doing so.

Eleven countries achieved at least 95% coverage with MCV1 (first dose of measles-containing vaccine) at national level and in the majority of the districts, and 21 provided a routine second dose of MCV with variable levels of coverage. To boost population immunity, nationwide measles immunization campaigns targeting a wide age range were conducted in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Syrian Arab Republic and Sudan and child health days in Somalia. Measles case-based laboratory surveillance is implemented in all countries. Despite the current challenges in the Region, six countries have reported very low incidence of measles (<5 cases/million population), with three of these continuing to achieve zero incidence and close to verifying measles elimination. The crisis in the Syrian Arab Republic resulted in outbreaks of measles in Iraq, Lebanon and Syrian Arab Republic, as well as Jordan which had been free of measles for 3 years. In response, measles supplementary immunization activities were conducted with strong support from WHO and in close collaboration with several partners. In line with consolidating the efforts to achieve the measles elimination target, the third regional Vaccination Week focused on measles elimination under the theme “Stop measles now”.

Elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus was documented in Iraq. Five countries have not yet achieved elimination (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen) and Djibouti has still to document it.

Progress with regard to the introduction of new vaccines was substantial. Hib vaccine is now in use in 20 countries, pneumococcal vaccine in 14 countries and rotavirus vaccine in 8 countries. These figures exceeded the target for 2013. Hib vaccine was introduced in Somalia, pneumococcal vaccine in Afghanistan and Sudan, and rotavirus vaccine in Saudi Arabia. Libya introduced pneumococcal, rotavirus, HPV and meningococcal vaccine and Sudan successfully implemented the second phase of the meningococcal A conjugate vaccine campaign (reaching more than 95% coverage).

In order to maintain achievements, WHO extended substantial support to countries. Comprehensive immunization programme reviews, reviews of vaccines surveillance networks, and assessment of effective vaccine management were conducted in several countries. Substantial support was also provided to countries preparing to introduce new vaccines. Capacity was strengthened in countries in regard to data quality, surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases, monitoring and evaluation, as well as laboratory surveillance for measles, bacterial meningitis, bacterial pneumonia and rotavirus. WHO continued to coordinate the external laboratory quality control system and accreditation of measles laboratories.

The implementation of vaccine regulation and production faces a number of challenges relating to the lack of human resources with appropriate skills, as well as a lack of financial resources. Regulatory capacity was strengthened in the five countries producing vaccines, especially in the area of vaccine pharmacovigilance, vaccine safety communication and vaccine licensing. In terms of post marketing surveillance, four countries – Islamic Republic of Iran, Morocco, Sudan and Tunisia – are currently contributing to the global vaccine safety initiative that was initiated in 2012.

Health security and regulations

The incidence of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases poses a perennial threat to regional health security. Substantial support was provided by WHO to manage outbreaks of hepatitis E in South Sudan, hepatitis A in Jordan and northern Iraq, dengue fever in Pakistan, meningococcal meningitis in South Sudan, yellow fever in Sudan and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In addition, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), the novel respiratory virus that emerged in 2012, continued to spread further geographically. Six countries in the Region have now reported laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV.

In 2013, WHO provided strategic and technical support for risk assessment, field investigation and detection of widespread outbreaks across many countries which resulted in limiting their spread and minimizing health impact. Field missions were conducted in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia for control of the outbreaks caused by MERS-CoV. Outbreaks of hepatitis A were effectively contained in Jordan and northern Iraq by the national health authorities following implementation of public health measures recommended by WHO after joint field investigations. Epidemic readiness measures were scaled up in all countries affected by the Syrian crisis through establishment of early warning surveillance systems for disease outbreaks in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syrian Arab Republic, as well as strengthening of laboratory diagnostic capacities for epidemic detection.

In view of the persistent threat from MERS-CoV virus, the sentinel surveillance system for severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) was expanded in several countries with a view to sustaining the capacity to detect diagnose, and respond to outbreaks caused by any novel influenza or respiratory viruses. Public health vigilance for MERS-CoV was maintained throughout the year through enhancing surveillance and improving other regional public health preparedness measures. Technical meetings, consultations and training courses were organized while strategic guidance and advisories were produced collectively with other national health authorities to improve regional preparedness for this novel infection.

Owing to the lack of representative data, the burden and magnitude of the resistance patterns of pathogens to different micro-organisms remains poorly understood in the Region. In response to Regional Committee resolution EM/RC 60/R.1, a set of strategic directions was developed through a consultative process to translate WHO’s six policy package on antimicrobial resistance into a framework for action on containment of antimicrobial resistance. A strategic framework was developed for early detection, diagnosis and control of zoonotic diseases. Progress was made also in developing a strategic framework for prevention and control of cholera and other epidemic diarrhoeal diseases, and a strategic framework for prevention and control of acute respiratory infections with epidemic potential.

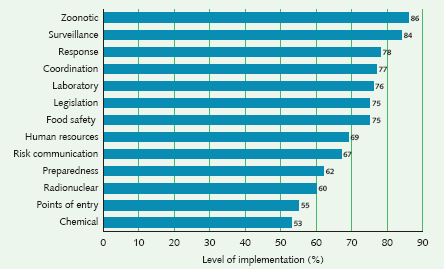

By June 2012, only one country (Islamic Republic of Iran) was ready for implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005); all other Member States obtained a 2 year extension for implementation to June 2014, except Somalia which was not able to meet the requirements. Despite progress in meeting the requirements (estimated at 70% across the Region by end 2013), particularly in surveillance, response, laboratory and zoonotic capacities, many remain a challenge. This is especially the case with regard to capacities to handle chemical, radiological and nuclear events and for points of entry and preparedness. This is due to the lack of supportive public health laws and other legal and administrative instruments; insufficient coordination among the different stakeholders at country level and with neighbouring countries; high turnover of qualified personnel; insufficient financial capacity to cover planned activities; and geopolitical instability in some States Parties. Fig. 2 shows the implementation level with regard to capacities across the Region by end 2013.

The emergence of MERS-CoV further highlighted the importance of the Regulations and that epidemic and pandemic threats are on the rise. WHO worked closely with States Parties to raise awareness about the Regulations and associated commitments and facilitated experience sharing between countries and with other WHO regions. Collaboration was strengthened with international organizations, United Nations agencies, nongovernmental organizations and WHO collaborating centres and networks of excellence to support countries to step up the implementation of the Regulations. Support for national authorities in their efforts to respond to outbreaks, including the MERS-CoV outbreak, was managed within the framework of the Regulations.

WHO continued to provide technical support to States Parties to review the status of implementation and to develop national plans to address the gaps in capacity requirements. It is expected that a considerable number of State Parties in the Region will request further extension to implement the requirements by June 2016.

Figure 2: International Health Regulations (2005): level of core capacity implementation in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2013

Source: Summary of States Parties 2013 report on IHR core capacity implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

[1] For tuberculosis case detection, WHO receives data a year later, thus case detection data relate to 2012 and treatment outcome data to 2013.

[2] South Sudan became a Member of the African Region in May 2013. |

|

|

Communicable diseases |

|

|

|

Communicable diseases are estimated to be responsible for around one third of all deaths and one third of all illnesses in the Region. Despite successes in eliminating and eradicating some of these diseases in some countries, the Region continues to suffer from a significant burden of communicable diseases which hampers socioeconomic development. The importance of communicable disease control has increased in recent years due to increased travel, trade, migration and emergence of new infections. In addition to the chronic challenges of weak health systems, inadequate commitment and financing for communicable disease control have resulted in delay to achievement of regional targets. Several countries are facing political instability, social unrest, ongoing conflict and insecurity, all of which have an impact on control of communicable diseases. In this section, we address four thematic areas: poliomyelitis eradication; HIV, tuberculosis, malaria and tropical diseases; immunization and vaccines; and health security and regulations.

Poliomyelitis eradication

The poliomyelitis eradication programme is a high priority initiative that is directly supervised by the Regional Director. All countries of the Region are free from polio except Afghanistan and Pakistan where poliovirus circulation has never been stopped. The remaining identified reservoirs of poliovirus in Pakistan are the Quetta block (Pishin, Kilabdella and Quetta) in Baluchistan, Gadap Town in Karachi and Khyber Agency in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), while in Afghanistan, Kandahar and Helmand provinces in the southern region are the main reservoirs. Persistent transmission in Pakistan and Afghanistan has held back global polio eradication, and is a threat to polio-free countries. Somalia and Yemen are considered at high risk because insecurity has led to low population immunity resulting in the circulation of vaccine-derived polioviruses. Djibouti, South Sudan and the Syrian Arab Republic are all being kept under close surveillance.

2012 witnessed major achievements. Pakistan reported 58 polio cases in 2012 compared to 198 in 2011 while Afghanistan reported 37 cases compared to 80 in 2011. Pakistan developed and implemented an augmented national emergency action plan, addressing the various challenges, including consistent government oversight, ownership and accountability at each administrative level. Significant efforts and initiatives were made by the programme, particularly the adequate and appropriate use of bivalent oral polio vaccine, introduction of short-interval additional doses, the development of comprehensive sub-district plans, introduction of a surge of support staff by WHO and UNICEF at the implementation level, improvements in the monitoring system through the use of lot quality assurance sampling and maintenance of a very sensitive surveillance system supported by a well-functioning regional reference laboratory. The Government of Afghanistan also developed a national emergency action plan which includes improving management and accountability, reducing inaccessibility, increasing community demand and strengthening routine immunization. Permanent polio vaccination teams and district immunization management teams were put in place in poorly performing districts to improve routine immunization services in 28 districts. Strong cross-border coordination is needed between both countries in order to: map children who have been missed and identify why they are being missed; reach and vaccinate each and every child across the border; and ensure continuous communication at the operational level and between the two governments. A management and accountability framework has been introduced in the high-risk districts of both Member States.

However, the programme in Pakistan is facing several new challenges, including a ban on vaccination in North and South Waziristan, and resistance from the militant factions in Karachi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and parts of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). Efforts are needed to de-link the programme from the disinformation being propagated around it and to present a neutral interface. In Afghanistan, conflict and inaccessibility hamper progress. These challenges are currently being addressed by strengthening the communications component of the programme, establishment of the Islamic Advisory Group and strengthening regional ownership of the polio programme. No country is completely immune from reintroduction of polio if transmission remains in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Support from other countries of the Region is critical to success. The Regional Committee pledged to unite for a polio-free Region and one of the challenges for 2013 is to translate that pledge into concrete action.

Somalia remains at high risk of a wild poliovirus outbreak due to the large pool of inaccessible and unvaccinated children if importation were to occur. The major challenge is reaching and vaccinating an estimated 800 000 target children in inaccessible areas due to insecurity. The vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outbreak in Yemen is indicative of the large population immunity gap which resulted from chronic low routine immunization coverage and lack of high-quality supplementary immunization activities. In response to the outbreak, Yemen conducted three national immunization days and one subnational immunization day. Oral polio vaccine (OPV) was also added to a measles catch-up campaign.

Ten polio-free countries at risk of importation (Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Islamic Republic of Iran, Jordan, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, South Sudan and Syrian Arab Republic) conducted subnational immunization days with a focus on geographic areas with high-risk populations and low routine immunization coverage, in an effort to boost population immunity of high-risk groups. Other vaccination opportunities, such as measles campaigns and Child Health Days, were used to deliver additional doses of oral polio vaccine (OPV) to help boost population immunity.

Key acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance indicators (i.e. non-polio AFP rate and percentage of adequate stools) at the national level are reaching international certification standards. However, at the subnational level, there are gaps, which are more significant for the countries that have been polio-free for many years. All the countries of the Region have maintained the expected non-polio AFP rate per 100 000 children under the age of 15 years except for Morocco, which is close to the expected rate. The percentage of AFP cases with adequate stool collection is above the target of 80%, except in Djibouti, Lebanon and Tunisia.

HIV, tuberculosis, malaria and tropical diseases

The HIV epidemic has continued to spread fast through the Region. The latest estimates show that approximately 560 000 people are living with HIV in the Region. Although the overall prevalence in the general population is still low, the proportion of newly infected people among all people living with HIV is the highest globally. AIDS-related deaths have almost doubled in the past decade among both adults and children, reaching a total of 38 400 in 2011. HIV treatment coverage is only 13%, the lowest among WHO regions. Lack of political commitment, inadequate access to health services for populations at higher risk, high stigma and discrimination, and weaknesses of health systems continue to challenge effective control and delivery of care.

WHO focused its support to Member States on the development of HIV testing and treatment guidelines and capacity-building in service delivery. Guidance was provided on service-delivery to populations at higher risk that are difficult to reach with conventional health services and countries were supported to develop novel service-delivery approaches, including through community-based organizations. Collaboration with the regional knowledge hub on HIV surveillance in the Islamic Republic of Iran was maintained to strengthen the institution’s role as a regional resource and training centre.

Concerned about the lack of progress in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the Region, WHO in partnership with UNICEF, UNFPA and UNAIDS launched a regional initiative to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV (eMTCT). The initiative adopts the overall global goals of reducing the number of new HIV infections among children by 90% by 2015, and reducing the number of AIDS-related maternal deaths by 50%, also by 2015. It promotes a comprehensive approach including preventing unintended pregnancies among women living with HIV; preventing transmission of HIV from HIV-infected pregnant women to their children; and providing treatment, care and support to mothers, children and families living with HIV.

In 20111, 11 countries achieved a tuberculosis case detection rate of 70%, 13 achieved 85% treatment success rate and 12 developed national strategic plans for 2011–2015. The laboratory network was expanded, especially for culture and drug susceptibility testing. Technical support was extended in drug management and promotion of prequalification of pharmaceutical companies. The electronic nominal recording and reporting system (ENRS) is now being used in five countries and the web-based surveillance system (WEB TBS) was introduced in several countries. Eleven countries received support in conducting surveys to assess the burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Review missions were conducted in five countries. Several countries received technical support in conducting surveys and studies to estimate the extent of underreporting of tuberculosis cases and burden.

An estimated 46% of the population was living in areas at risk of local malaria transmission in 2011. Countries reported a total of 6 789 460 malaria cases (see Tables 2 and 3), of which only 16.8% were confirmed parasitologically and the rest were treated based on clinical diagnosis. Six countries accounted for more than 99.5% of the confirmed cases in 2011 (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Yemen). According to 2010 data, the number of estimated malaria deaths was 15 000. Malaria control and elimination still face several challenges. Access to facilities for parasitological diagnosis in countries with a high burden of malaria is limited and the quality is poor. Resistance to anti-malarial drugs is growing in P. falciparum endemic countries. Malaria surveillance, monitoring and evaluation are weak and the compliance of private providers with national treatment guidelines is low. Insecurity, climate change and natural disasters are additional challenges for malaria control; for example the malaria situation in Pakistan has worsened since the heavy floods in 2010. Malaria-free countries also face the challenge of increasing imported malaria resulting from huge population movements, both legal and illegal.

Among the achievements made, Iraq was included among the non-malaria-endemic countries after three years with no reported local transmission. The Islamic Republic of Iran and Saudi Arabia achieved targets of more than 80% coverage of malaria control and elimination interventions. Other countries showed good progress in coverage with malaria interventions such as long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), but have yet to achieve the target of more than 80%. By the end of 2012, the operational coverage of LLINs in Sudan had increased to more than 50%. In Afghanistan, the proportion of households with at least one LLIN increased from 9.9% in 2009 to 43.4% in 2011. In the same period, the proportion of children under 5 years of age who slept under LLINs the night before the survey increased from 2% to 32%. WHO continued to support capacity-building of national programmes through regional trainings on malaria planning and management, microscopy and quality assurance, using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and elimination. Djibouti finalized a programme review, while the Islamic Republic of Iran, South Sudan, Sudan and Yemen are at different stages of such a review. Programme reviews were also supported in Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. With technical support from WHO at the country and regional level, countries succeeded in signing agreements for extending Global Fund grants.

Several activities were carried out to address vector-borne diseases in the Region. WHO focused its support on the implementation of the regional Framework for action on the sound management of public health pesticides, on demonstration studies for sustainable alternatives to DDT and on strengthening national vector control capabilities in Member States. Joint work was carried out with countries to develop a regional database on insecticide resistance. A regional consultation on insecticide resistance management was conducted and participating countries agreed to incorporate an insecticide resistance management component into the national integrated vector management strategies and continue to strengthen entomological surveillance.

With regard to neglected tropical diseases, human African trypanosomiasis remains a challenge in South Sudan. The decline achieved in the number of cases over recent years, and the consequently higher proportional cost of treatment per patient, is now making it difficult to get partners involved in control activities. Accessibility during the rainy season represents a major issue for several tropical disease programmes in South Sudan and Sudan.

A 50% reduction was observed in the number of cases of guinea-worm disease in South Sudan in 2012 compared to 2011 and only 179 villages remain endemic. The lymphatic filariasis elimination programmes in Egypt and Yemen completed the elimination phase and capacity was built to assess transmission for elimination verification. Onchocerciasis was certified as having been eliminated from Abu Hamad, the largest endemic focus in Sudan. Praziquantel distribution in the three schistosomiasis-endemic countries (Yemen, Sudan and Somalia) increased by 70% despite the challenge of insecurity. The enhanced global strategy 2011–15 for leprosy elimination and its operational guidelines were translated into Arabic and the strategy is being implemented. The rapid diagnostic field test for visceral leishmaniasis is now widely available and has shortened the treatment from 30 to 15 days.

|

Table 2. Reported malaria cases in countries with high malaria burden

|

|

Country

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

|

Total reported cases

|

Total Confirmed

|

Total reported cases

|

Total Confirmed

|

Total reported cases

|

Total Confirmed

|

|

Afghanistan

|

392 463

|

69 397

|

482 748

|

77 549

|

391 365

|

54 840

|

|

Djibouti

|

3 962

|

1 019

|

624

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Pakistan

|

4 281 356

|

240 591

|

334 589a

|

334 589

|

289 759a

|

289 759

|

|

Somalia

|

24 553

|

24 553

|

41 167

|

3 351

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

South Sudan

|

900 283

|

900 283

|

795 784

|

112 024

|

1 198 358

|

NA

|

|

Sudan

|

1 465 496

|

720 557

|

1 246 833

|

506 806

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Yemen

|

198 963

|

106 697

|

142 147

|

90 410

|

153 981

|

105 066

|

NA: not available

aConfirmed cases only

|

Table 3. Parasitologically-confirmed cases in countries with no or sporadic transmission and countries with low malaria endemicity

|

|

Country

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

|

Bahrain

|

90

|

0

|

186

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Egypt

|

85

|

0

|

116

|

0

|

206

|

0

|

|

Iraq

|

7

|

0

|

11

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Iran, Islamic Republic of

|

3 031

|

1 847

|

3 239

|

1 710

|

NA

|

532

|

|

Jordan

|

61

|

2

|

58

|

0

|

117

|

0

|

|

Kuwait

|

343

|

0

|

476

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Lebanon

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

115

|

0

|

|

Libya

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

88

|

0

|

|

Morocco

|

218

|

0

|

312

|

0

|

359

|

0

|

|

Oman

|

1 193

|

24

|

1 531

|

13

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Palestine

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Qatar

|

440

|

0

|

673

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Saudi Arabia

|

1 941

|

29

|

2 788

|

69

|

3 406

|

83

|

|

Syrian Arab Republic

|

23

|

0

|

48

|

0

|

42

|

0

|

|

Tunisia

|

72

|

0

|

67

|

0

|

79

|

0

|

|

United Arab Emirates

|

3 264

|

0

|

5 242

|

0

|

5 165

|

0

|

NA: not available

Immunization programmes in the Region are confronted by several challenges. The progress towards coverage targets continues to be affected by the security situation, particularly in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen. The global shortage of DTP and DTP-HepB and pentavalent vaccine also affected Egypt, Islamic Republic of Iran and Libya. Inadequate managerial capacity and commitment to routine immunization remained visible challenges in some countries in 2012. High-level support to routine immunization, especially in Afghanistan and Pakistan, is urgently needed. Inadequate financial resources, particularly for implementation of measles and tetanus supplementary immunization, introduction of new vaccines in middle-income countries and co-financing in GAVI eligible countries, and implementation of activities pertaining to improvement of vaccination coverage in countries with low coverage continued to be issues of concern. Allocation of government resources and the support of partners are needed to scale up the response against vaccine-preventable diseases. In this regard the Decade of Vaccines and the Global Vaccine Action Plan represent opportunities for resource mobilization which countries can make use of.

Technical support was extended to countries in a number of areas including: assessment of the different areas of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) and development of plans for improvement; ensuring an adequate logistics system; introduction of new vaccines; development of applications for support from the GAVI Alliance; strengthening surveillance; and monitoring and evaluation of EPI. Although vaccination coverage data for 2012 are not available yet, preliminary reports indicate that 15 countries in the Region continued to achieve the target of 90% routine vaccination coverage while Djibouti was close to achieving the target. Egypt and Tunisia were able to maintain high routine vaccination coverage above 95%, despite the challenges, and Somalia and South Sudan also saw an increase in coverage. However, the situation in the Syrian Arab Republic is alarming and vaccination coverage has dropped significantly. The third regional vaccination week was successfully implemented in April 2012 with the theme “reaching every community”.

Nine countries reported very low incidence of measles (<5 per million population) and are close to achieving measles elimination (Figure 4). Regarding implementation of the regional measles elimination strategy, fourteen countries achieved above 95% coverage with the first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) and a second dose (MCV2) is now being implemented in 21 countries following its introduction in Sudan and Djibouti. As for surveillance, all countries have implemented measles case-based laboratory surveillance either nationwide (20 countries) or as sentinel surveillance (Djibouti, Somalia and South Sudan). Local measles genotypes, which are necessary for validating measles elimination, were identified in 22 countries.

Figure 4 Incidence rate per million population of confirmed measles cases, 2012

Immunization and vaccines

Introduction of new life-saving vaccines made further progress in 2012. Hib vaccine is now in use in 20 countries and is expected to be introduced in the remaining countries soon. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is now in use in 11 countries and rotavirus vaccine in 7 countries. The first phase of a meningococcal A conjugate vaccine campaign in Sudan was implemented. Pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines are expected to be introduced soon in more countries thanks to the support of the GAVI Alliance. The main challenge facing new vaccines introduction is the unaffordability of the new vaccines for middle-income countries. WHO is working to enhance new vaccines introduction, particularly in middle-income countries through establishing a regional pooled vaccine procurement system, advocacy for allocation of more national resources and strengthening evidence-based decision-making and national immunization technical advisory groups.

Health security and regulations

In 2012, there was an unprecedented rise in the incidence of emerging and re-emerging communicable diseases, posing constant threats to regional health security. Outbreaks occurred periodically throughout the year affecting a large number of countries and causing some of the worst human misery ever seen in the Region. The outbreaks included avian influenza A (H5N1) in Egypt, cholera in Iraq and Somalia, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Afghanistan and Pakistan, diphtheria in Sudan, measles in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Somalia, nodding syndrome and hepatitis E in South Sudan, yellow fever in Sudan, West Nile virus infection in Tunisia and the influenza outbreak seen towards the end of the year in Palestine and Yemen caused by influenza A (H1N1). The emergence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Jordan, Qatar and Saudi Arabia with a high case fatality rate, on top of these outbreaks, was a stark reminder of the increase in epidemic-prone emerging diseases in the Region. While the looming threat of a pandemic from avian influenza still persists in the Region, the appearance of MERS-CoV in humans greatly underscored the vulnerability of the Region to the threat of emerging diseases. The ongoing conflicts and chronic humanitarian emergencies prevailing in many countries and resulting in large numbers of displaced populations are among the major risk factors for the spread of new diseases.

Early detection and rapid response to contain epidemic threats from emerging diseases remain the biggest challenge. WHO has continued to provide strategic technical support to countries to develop, strengthen and maintain adequate surveillance and response capacity to detect assess and respond to public health events of both national and international concern. As part of the ongoing efforts to improve the Region’s collective preparedness and response capacities, WHO invested in improving sub-regional and local capacities for epidemic intelligence and risk assessment for informed public health actions to contain epidemic threats. Pakistan received support in organizing an international conference on dengue fever which led to recommendations on surveillance, detection, management, vector control, behavioural interventions and emergency response in outbreaks.

WHO coordinated with its Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) partner institutions and WHO collaborating centres for the deployment of experts and laboratory resources for outbreak response and containment operations in a number of countries at risk of international spread of epidemics where the national outbreak response operations are not adequate to contain the threats of international spread given the size and magnitude of these outbreaks. These included yellow fever in Sudan, nodding syndrome in South Sudan, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Jordan, Qatar and Saudi Arabia and severe influenza in Palestine. In order to further strengthen the infection prevention and control programme in the Region, consultations were held to develop tools for surveillance of health-care associated infections and guidelines for preventing infections associated with health care from acute viral haemorrhagic fevers.

The International Health Regulations 2005 (IHR) are an international legal agreement binding on all WHO Member States. All State Parties in the Region, except the Islamic Republic of Iran, fell short of the implementation goals for June 2012. Requests for a 2-year extension supported by plans of implementation were submitted by 17 Member States. Three (Libya, Pakistan and United Arab Emirates) submitted only requests for extension and one country (Somalia) has not complied with the extension requirements. Countries have faced a number of challenges during the implementation of regulations. These include: lack of supportive public health laws and other legal and administrative instruments; insufficient coordination among the different stakeholders at country level and with neighbouring countries; high turnover of qualified personnel; and insufficient financial capacity to cover planned activities.

There was marked progress in developing and sustaining several of the requirements for implementation of the regulations in the Region, with regional implementation of the requirements estimated at 67%, based on data collected through the 2011 monitoring questionnaire. However, many requirements remain a challenge and need further work. These include: implementing the new legislation and national policies put in place to facilitate the implementation of the regulations; testing existing coordination mechanisms among the different stakeholders; evaluating the early warning function of the indicator-based surveillance; establishing event-based surveillance; and strengthening cross-border surveillance. Furthermore, programmes for protecting health care workers and monitoring systems for antimicrobial resistance need to be established. National preparedness and response plans need to be tested. Many requirements in the general obligations, as well as effective surveillance and response at points of entry also need to be fulfilled. Meeting the requirements for detecting and responding to foodborne disease and food contamination and in detecting and responding to chemical and radionuclear emergencies are other areas that need to be considered. Effective communications, coordination and collaboration among different sectors and enhancement of human resources are vital to efficient application of the regulations.

1 For tuberculosis case detection, WHO receives data a year later, thus case detection data relate to 2011 and treatment outcome data to 2012. |

|

Communicable diseases |

|

|

Poliomyelitis eradication

The global progress towards poliomyelitis eradication in 2014 was substantial. However, the disease remains endemic in the Region. Of the 215 polio cases reported globally in the second half of 2014, 213 (99 %) are from the Eastern Mediterranean Region (Pakistan 192 cases, Afghanistan 20 cases and Somalia 1 case). Iraq and the Syrian Arab Republic also reported poliomyelitis cases in the first half of 2014 (two cases and one case respectively).

Pakistan suffered from the highest levels of wild poliovirus transmission in more than a decade. It faced significant and unique challenges, including bans on immunization by militant groups in parts of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas which restricted access to children, and multiple deadly attacks on frontline workers during polio campaigns in several parts of the country. Health workers and volunteers continued to demonstrate great courage in carrying out immunization activities. In addition to access and security issues, governance, operational and communication issues hampered eradication efforts in endemic parts of the country.

In Afghanistan, both endemic transmission and importations of wild poliovirus from Pakistan occurred, and barriers to access and the inadequate quality of some campaigns hindered reaching every child with vaccine, particularly in the eastern and southern regions. Nevertheless, the national programme has continued to implement activities with great determination.

In 2015, if the trend continues, it is highly likely that Afghanistan and Pakistan will be the only two countries in the world with active wild poliovirus transmission. This transmission is currently the greatest threat to the achievement of global eradication. The spread of the virus from these reservoirs poses a significant risk to polio-free countries in the Region.

Pakistan is implementing a detailed plan of action for the low transmission season (December 2014 to May 2015), focusing on innovative strategies and on endemic transmission zones within the country. Afghanistan also has an emergency action plan which aims to ensure high levels of immunity for the whole population, while interrupting transmission in the remaining infected zones. Full implementation of these plans will be critical to making progress with eradication in 2015. Review of epidemiology during the first half of 20015 already demonstrates a positive trend with a substantial reduction of cases compared to 2014.

The challenge of the spread of poliomyelitis in the Region brought an unprecedented response from Member States. The multi-country response to the Middle East outbreak which began in late 2013 was swift, coordinated and of high quality and, despite the conflicts and population displacement in the affected countries and their neighbours, this averted a major epidemic. The Syrian Arab Republic has not confirmed a case since January 2014 and Iraq since April 2014. In the Horn of Africa, following a sustained multi-country outbreak response there is also evidence that transmission in Somalia is coming under control, with only 5 cases reported in 2014, the latest having onset in August 2014.

The polio partnership is enhancing its support to both endemic countries through multiple interventions. These include: deploying the best available professionals; mobilizing resources to comprehensively implement all the planned activities; developing strong coordination mechanisms under the umbrella of the emergency operation centres at the federal and provincial levels; monitoring progress closely through development of a comprehensive monitoring framework and regular programme review by the technical advisory group; and implementing a strict accountability framework to ensure a high level of staff performance.

In 2015, WHO will escalate its support to the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan to stop endemic transmission of poliovirus. WHO will continue to support other countries of the Region to enhance the sensitivity of the surveillance system and to improve the capacity to detect early and effectively respond to poliovirus importations. The mechanisms of the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) are being used in order to reduce the risk of the international spread of poliovirus and to ensure a robust response to new polio outbreaks in polio-free countries. Support will be provided to Member States in developing plans for phased withdrawal of oral polio vaccine and containment of wild and vaccine-derived polio viruses.

The Islamic Advisory Group established at the regional level and a national advisory group in Pakistan are promoting polio eradication and immunization in general. The scope of work of the Islamic Advisory Group will be expanded to help in addressing other key health issues in the Region.

HIV, tuberculosis, malaria and tropical diseases

The HIV epidemic is still growing despite the overall prevalence remaining low. Regionally, the number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) who are receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) increased from 32 000 in 2013 to 38 000 in 2014. Despite this progress, ART coverage has not increased significantly and at 10% still remains far from global targets.

Within the framework of the regional initiative to end the HIV treatment crisis, WHO provided technical and financial support to priority countries to revise their treatment guidelines and train health care providers. Thirteen countries now have national guidelines in line with the current WHO recommendations. Five countries received support to conduct HIV test–treat–retain cascade analysis, to establish evidence-based HIV testing and treatment targets and to develop treatment acceleration plans. Six countries developed national strategic and operational plans.

A regional viral hepatitis plan for 2014–2015 was developed and funds are being sought to enable implementation. The focus of activities is on the two high-burden countries, both of which developed national hepatitis strategies.

WHO is developing three related global health sector strategies for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections. Two regional consultations will be organized in the first half of 2015 to provide regional inputs to the HIV and viral hepatitis strategies.

During 2013 1 , over 448 000 cases of all forms of tuberculosis were notified in the Region. Nearly half of these were in two high-burden countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Still, 40% of estimated cases are missed or not reported in the Region. The treatment success rate was 87%, slightly higher than the global target of 85 %, and this has been maintained for 2 years.

10 countries have achieved or exceeded the 70% target of case detection and 9 countries have reached or exceeded the global target of 85% treatment success rate. There was slow but steady improvement in regard to management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Out of 17 000 estimated cases, only around 3687 were detected and 2013 were put on treatment. The treatment success rate reached 64%.

The current crises have had an impact on tuberculosis control. Population movements, the destruction of many health facilities, including tuberculosis facilities, and the deterioration of the economic situation have affected both patients and human resources. One of the implications of the current situation is the decrease in case detection (58% compared to 63% in 2012). Meanwhile, further scale-up of MDR-TB treatment is hindered by lack of proper infrastructure and financial constraints.

In response to the regional challenges, WHO developed guidance on control of tuberculosis in complex emergencies, as well as a package of tuberculosis services for cross-border tuberculosis and MDR-TB patients. The Green Light Committee supported countries to improve diagnostic capacity and scale up treatment of MDR-TB . Monitoring missions to seven countries reviewed the MDR-TB management situation and advised on challenges. Access to new diagnostics continued to increase in the Region, with 4% of tuberculosis laboratories now using LED microscopy. However, domestic financing for tuberculosis controls continues to be less than 30%.

Within the strategic direction to scale up planning for tuberculosis control, review missions were conducted in several countries in 2014. Countries were supported technically to ensure smooth access to better financing from the Global Fund.

In 2014, six countries had areas of high malaria transmission (see Table 1) while transmission is focal in Islamic Republic of Iran and Saudi Arabia. The number of deaths due to malaria in the Region has more than halved since 2000 (from 2166 deaths compared with 1027 in 2013). In 2014, Pakistan and Sudan accounted for over 90% of the deaths (67% and 24%, respectively). The number of confirmed malaria cases reported in the Region decreased from 2 million in 2000 to 1 million in 2013, with Sudan and Pakistan accounting for 84% of cases (57% and 27% respectively).

Table 1. Reported malaria cases in countries with high malaria burden

| Country Name |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

| Total reported cases |

Total Confirmed |

Total reported cases |

Total Confirmed |

Total reported cases |

Total Confirmed |

| Afghanistan |

391365 |

54840 |

319742 |

46114 |

290079 |

83920 |

| Djibouti |

25 |

25 |

1684 |

1684 |

NA |

NA |

| Pakistan |

4285449 |

290781 |

3472727 |

281755 |

3666257 |

270156 |

| Somalia |

59709 |

18842 |

60199 |

43317 |

NA |

NA |

| Sudan |

1001571 |

526931 |

989946 |

592383 |

1207771 |

NA |

| Yemen* |

165678 |

109908 |

149451 |

102778 |

70679 |

49336 |

* The estimated reporting completeness is 30% in 2014 due to current situation in Yemen

Seven countries (Afghanistan, Iraq, Islamic Republic of Iran, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Syrian Arab Republic) have achieved MDG6 and the targets of resolution WHA58.2 as related to malaria. Elimination programmes have been successfully implemented in Islamic Republic of Iran and Saudi Arabia, with only 370 and 51 local cases, respectively, reported in 2014 (Table 2). Iraq has not reported any local cases since 2009. However, it has been difficult to measure the progress towards MDG6 in five of the countries with a high burden of malaria owing to the weakness of diagnostic and surveillance systems. The limited WHO capacity at country level to ensure sustained technical support, as well as inadequate allocation of funds from national resources in priority endemic countries and dependency on external funds, have also affected progress.

Table 2. Parasitologically-confirmed cases in countries with no or sporadic transmission and countries with low malaria endemicity

|

Country

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

Total reported cases

|

Autochthonous

|

|

Bahrain

|

233

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Egypt

|

206

|

0

|

262

|

0

|

313

|

22

|

|

Islamic Republic of Iran

|

1629

|

787

|

1373

|

519

|

1238

|

370

|

|

Iraq

|

8

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

|

Jordan

|

117

|

0

|

56

|

0

|

102

|

0

|

|

Kuwait

|

358

|

0

|

291

|

0

|

268

|

0

|

|

Lebanon

|

115

|

0

|

133

|

0

|

119

|

0

|

|

Libya

|

88

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Morocco

|

364

|

0

|

314

|

0

|

493

|

0

|

|

Palestine

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Oman

|

2051

|

22

|

1451

|

11

|

1001

|

15

|

|

Qatar

|

708

|

0

|

728

|

0

|

643

|

0

|

|

Saudi Arabia

|

3406

|

82

|

2513

|

34

|

2305

|

51

|

|

Syrian Arab Republic

|

42

|

0

|

22

|

0

|

21

|

0

|

|

Tunisia

|

70

|

0

|

68

|

4

|

98

|

0

|

|

United Arab Emirates

|

5165

|

0

|

4380

|

0

|

4575

|

0

|

In 2014, in-depth programme reviews, updating of national strategic plans and development of insecticide resistance management strategies were supported in different countries. The global technical strategy 2016–2030 was developed through a comprehensive consultative process with all countries; seven regional consultations were conducted in 2014. A regional action plan to implement the strategy will be presented to the Regional Committee in 2015. The goal of this plan is to interrupt malaria transmission in areas where it is feasible and to reduce the burden by more than 90% in areas where elimination is not immediately possible, so that malaria is no longer a public health problem or a barrier to social and economic development.

Promising achievements have been made in schistosomiasis control and elimination, with Yemen an excellent example of how a strong partnership among national and international institutions can contribute to overcoming the most difficult challenges. In 2014, Yemen treated over 7.2 million children and adults with praziquantel and albendazole, despite the difficult security situation. Nationwide surveys have shown a sharp decrease in infection indicators and have indicated that schistosomiasis can be eliminated as a public health problem. In Sudan, 2.4 million people were treated with praziquantel following an increase in financial commitment by the Government and new partnerships.

Immunization and vaccines

Fourteen countries continued to achieve the target of 90% routine DTP3 vaccination coverage, but around 3 million children did not receive DTP3 vaccination, around 90% of which are in four countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia and Syrian Arab Republic). Thirteen countries achieved above 95% coverage with MCV1 (first dose of measles-containing vaccine) at national level and in the majority of the districts, while 21 countries provided a routine second dose of measles vaccine with variable levels of coverage. To boost population immunity, national or subnational measles supplementary immunization activities were conducted in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and Syrian Arab Republic. Measles case-based laboratory surveillance has been implemented in all countries, with 20 countries performing nationwide surveillance and 2 countries conducting sentinel surveillance. As a result, measles incidence was significantly lower than in 2013. Eight countries reported very low incidence of measles (<5 cases/million population) with two of these continuing to achieve zero incidence and scheduled to verify measles elimination in 2015.

2014 marked achievement of completing the introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccine in all countries. Rotavirus vaccine was introduced in the United Arab Emirates and rubella vaccine in Yemen as part of the measles/rubella vaccination campaign. Yemen is expected to introduce MR vaccine into routine immunization in 2015. Sudan implemented the first phase of a yellow fever campaign. Inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine (IPV) was introduced in Libya and Tunisia and all the countries using only oral poliomyelitis vaccine (OPV) are on track for introduction of IPV in 2015. Currently, pneumococcal vaccine is being used in 14 countries, rotavirus vaccine in 9 countries and IPV in 12 countries of the Region.

Achieving the various programme targets was constrained by several challenges. These included the current security situation that hindered access, as well as insufficient visibility of the immunization targets in many countries, inadequate managerial capacity and commitment to routine immunization, and lack of financial resources. In order to overcome these challenges, WHO intensified its support to countries, through comprehensive immunization programme reviews and assessment of effective vaccine management that were conducted in several countries. Support was also provided for development and updating of multi-year plans, resource mobilization, measles immunization campaigns, surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases, data quality, monitoring and evaluation, and introduction of new vaccines. Special attention was given to establishing and strengthening national technical advisory groups (NITAGs), which are now available in 21 countries. The Regional Office continued to provide technical and financial support to the regional surveillance networks for new vaccines introduction and measles/rubella surveillance in most countries.

WHO will continue to provide the necessary technical support and mobilization of resources for strengthening immunization programmes and achieving the targets. Priority activities for 2015 will include: ensuring access to high quality and safe vaccines through improving the procurement systems, support for comprehensive EPI reviews and updating of comprehensive multi-year plans (cMYP) in several countries; supporting proper planning and implementation of the reach every district (RED) approach in all districts with vaccination coverage below 80% in the low coverage countries, introduction of IPV in the 10 remaining countries, measles supplementary immunization activities, and hepatitis B serosurveys to document progress towards achieving the regional target; and strengthening EPI monitoring and evaluation. Advocacy for raising visibility of the EPI targets, especially measles elimination, and mobilization of high-level government support and commitment to routine immunization will be central.

Health security and regulations

The incidence of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases continues to escalate in the Region as evidenced by the fact that half the countries of the Region reported high incidence of emerging infectious diseases in the past year, sometimes with explosive outbreaks. These included avian influenza A (H5N1) in Egypt, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Afghanistan, Oman and Pakistan, dengue fever in Oman, Pakistan and Sudan, acute hepatitis A and E in Jordan, Lebanon and Sudan, and severe acute respiratory infection caused by influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus in Egypt and Pakistan. These events, apart from taking a huge toll of lives, have weakened the public health systems considerably. Infections caused by the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which emerged in the Region in 2012, continued to expand geographically, with persistent transmission, and cases have now been reported in 10 countries in the Region. Cases spiked in two countries last year owing, primarily, to secondary and nosocomial transmissions in health care settings and triggering heightened international concern for the emergence of a global public health emergency.

The ongoing humanitarian crisis in a number of countries has also weakened their public health systems, while displacing a large number of populations and exposing them to poor environmental health conditions and limited access to health care services. This provides ideal ground for proliferation of diseases and repeated outbreaks of epidemic-prone diseases have reported from these countries in crisis.

Towards the end of last year, the threat of introduction of Ebola virus disease (EVD) increased significantly owing to the connectivity of the Region with west African countries. The threat of importation of EVD into the already weakened and fragile health systems of countries affected by either humanitarian crisis or repeated epidemics, and the resultant public health implications, required public health preparedness and readiness measures across all countries to be stepped up in order to prevent any introduction of the disease and its spread in the Region.

In response to such frequent health security threats in the Region, WHO continued to work with the countries with a view to building, strengthening and expanding a sustainable public health system that is required under the International Health Regulations of 2005 to monitor detect, assess and contain acute and emerging health threats in the Region.

In response to Regional Committee resolution EM/RC/61/R.2, rapid assessments were conducted in 20 out of 22 countries to assess their capacity to deal with a potential importation of EVD. The assessments reviewed level of preparedness and readiness, identified critical gaps or areas of concern, and recommended urgent measures to mitigate risk of importation and spread. Following these assessments, a 90-day regional action plan was developed and implemented during the first half of 2015 to help countries address the critical gaps identified in the areas of surveillance and response, in order to be able to prevent, detect and undertake effective containment measures for control of EVD threats.

Because of the rapidly expanding threat from MERS-CoV, efforts continued to be made to support countries to improve public health preparedness measures, especially infection prevention and control in the health care environment. In view of the existing knowledge gaps regarding the mode of transmission of MERS-CoV, WHO provided support to finalize and implement a public health research protocol for understanding the risk factors that result in human infection. The results of this research initiative are expected, not only to unravel the mystery of the origin of this virus, but also to pave the way for preventing a human infection which is currently presumed to be of animal origin.

In view of the need to detect epidemic health threats in the countries that are affected by the ongoing crisis early, support was continued for scaling up and enhancing disease early warning systems and improving readiness measures for rapid and timely response to contain epidemics. The activities of WHO in the area of health security contributed significantly to accelerating progress in the implementation of the core capacities required under the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005). However, concerns remain for the countries that have yet to meet the deadline or achieve compliance with the requirements. By June 2014, which marked the expiry of the first two-year extension for IHR (2005) implementation, only eight States Parties in the Region had declared compliance with the requirements while the remaining 14 requested and were granted a second extension. With the expiry of the second extension due in June 2016, and in view of the recurrent health security threats in the Region, the sustainability, functionality and quality of the core capacities attained by the countries under the IHR (2005) are gaining increasing importance.

Also in response to Regional Committee resolution EM/RC61/R.2 as well as the recommendations of the IHR emergency and review committees, a set of strategic priorities at regional level, and a corresponding implementation plan, are being developed to plug the important gaps identified through the assessment of preparedness and readiness measures for EVD and to strengthen the required capacities. The third annual meeting of IHR stakeholders critically reviewed the gaps and the progress achieved so far and made pragmatic and targeted recommendations from a strategic perspective to push the IHR and global health security agenda forward. The strategic focus for country support under IHR now targets multisectoral coordination, legislative sufficiency, surveillance, response, infection control, zoonoses and food safety, all of which are key core capacity deficits that are common to States Parties.