Research article

N.A. Al-Sheyab,1 R. Gallagher,2 J.K. Roydhouse,3 J. Crisp 2 and S. Shah 4

جدوى تطبيق برنامج تثقيفي يرتكز على المدرسة عن الربو يقوده زملاء المراهقين في الأردن

نهاية الشياب، روبين قالقر، جاسيكا رويدهاوس، جاكي كريسب، سميتا شاه

الخلاصة: يستخدم برنامج العمل الخاص بالربو بين المراهقين (والمعروف اختصاراً بـ A A A) بنجاح في تعزيز المعارف، والوعي، وجودة الحياة لدى المراهقين الذين يعانون من الربو في أستراليا. وقام الباحثون بوصف إمكانية التطبيق والقبول والتكيُّف لهذا البرنامج التثقيفي حول الربو الذي أعد باللغة الإنكليزية، ويقوده الزملاء في مدرسة ثانوية للفتيات في شمالي الأردن. وأجرى البحث الارتيادي عمال صحيون يتحدثون باللغتين العربية والإنكليزية. وتم قياس الجدوى، والقبول، وإمكانية التكييف عن طريق معدَّلات المشاركة، والأسئلة المفتوحة الإجابات والتي استكملها القادة من الزميلات، ومجموعة بؤرية من الطالبات المستجدات، ومن الملاحظات اليومية. وقد استقبل العاملون والطالبات البرنامج استقبالاً حسناً، وبمستويات عالية من المشاركة. ونُظِرَ إيجابياً إلى أسلوب قيادة الزميلات. وأبلغت الطالبات أنهن استمتعن بالأنشطة التعليمية التفاعلية وفُرَص التمرين على اللغة الإنكليزية. وأبلغوا عن زيادة معارفهم ووعيهم بالربو، وأبلغت الطالبات المصابات بالربو عن تلقِّيهن مزيداً من الدعم من الزميلات. وخلص البحث إلى أن برنامج التثقيف حول الربو بقيادة الزملاء مجدٍ، ومقبول في سياق المدارس في الأردن.

ABSTRACT The Adolescent Asthma Action programme (Triple A) has been used successfully to promote asthma knowledge, awareness and quality of life in adolescents with asthma in Australia. We describe the feasibility and acceptability of an adaptation of this English-language, peer-led, asthma education programme in a girls’ high school in Northern Jordan. The pilot was conducted by bilingual health workers. Feasibility, acceptability and adaptability were measured through participation rates, open-ended questionnaires completed by peer leaders, a focus group for junior students and reflective journal notes. The programme was well-received by staff and students, with high levels of participation. The peer-led approach was viewed positively. Students reported that they enjoyed the interactive learning activities and the opportunity to practise English. The students reported increased asthma knowledge and awareness, with students with asthma reporting receiving more support from peers. A peer-led asthma education programme is feasible and acceptable in the Jordanian school context.

Faisabilité d'un programme d'éducation sur l'asthme en milieu scolaire mené par des pairs auprès d'adolescentes en Jordanie

RÉSUMÉ Le programme d'Action contre l'Asthme auprès des Adolescents (« Triple A ») a été mis en œuvre avec succès pour promouvoir les connaissances sur l'asthme et la qualité de vie auprès d'adolescents atteints d'asthme en Australie. Nous avons décrit la faisabilité et l'acceptabilité d'une adaptation de ce programme d'éducation sur cette maladie mené par des pairs en langue anglaise, auprès de filles d'un lycée du nord de la Jordanie. La partie pilote a été menée par des agents de santé bilingues. La faisabilité, l'acceptabilité et l'adaptabilité ont été mesurées au moyen des taux de participation, de questionnaires composés de questions ouvertes remplis par des camarades jouant un rôle d'animatrices, d'un groupe de discussion pour les élèves les plus jeunes et d'un cahier de notes de réflexion. Le programme a été bien accueilli par le personnel et les élèves, et les niveaux de participation étaient élevés. L'approche consistant à impliquer des pairs a été perçue positivement. Les élèves ont affirmé avoir aimé les activités d'apprentissage interactif et l'opportunité de parler l'anglais, et avoir accru leurs connaissances sur le sujet. Les élèves atteints d'asthme ont déclaré que leurs camarades les soutenaient davantage. Un programme d'éducation sur l'asthme mené par des pairs est réalisable et acceptable dans le contexte scolaire jordanien.

1Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery, and Health, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan (Correspondence to N.A. Al-Sheyab: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it )

2Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Health, University of Technology, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

3Sydney Nursing School; 4Primary Health Care Education and Research Unit, Primary Care and Community Health, Sydney West Area Health Service, School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Received: 13/10/10; accepted: 06/03/11

EMHJ, 2012, 18(5): 468-473

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of growth and development that promotes transition to adulthood but also increases vulnerability and risks for health-related behaviours [1,2]. Peer-led, school-based programmes, which utilize peers to serve as positive role models to encourage healthy behaviour, such as appropriate self-management of chronic diseases, have been used successfully in providing meaningful health education for adolescents [3]. Peer allies are usually trained to implement interventions that lead to a change in peers’ self-management behaviours, development of positive group norms, or improvement in adolescents’ ability to make healthy decisions [4,5].

The school setting is often used for adolescent health education programmes, as it enables programmes to reach large numbers of adolescents in the community, is familiar to students and promotes the opportunity to reinforce student knowledge through continuous social contact [6–10]. Compared with adult-led programmes, peer-led programmes are at least as effective in improving knowledge [11] and more effective in changing health behaviours and attitudes and promoting self-management in adolescents [12]. Adolescents with asthma are often difficult to access and tend to have greater difficulties in appropriate management and treatment [13], and therefore school-based programmes may be particularly appropriate for this group.

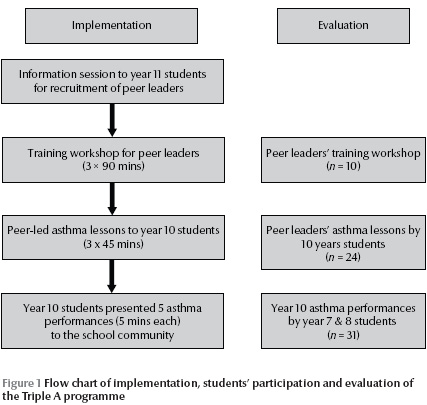

There is thus a need for such programmes globally, and particularly in Jordan where asthma is relatively common in adolescence and rates are comparable to some developed countries [14,15]. The aim of this study was to assess the feasibility in the Jordanian context of a peer-led, school-based asthma education programme which has improved health-related outcomes and knowledge in Australian adolescents [16]. The Adolescent Asthma Action (Triple A) programme uses a 3-step cascade process from senior to junior students to deliver asthma education (Figure 1) and has well-developed resources, including standardized training manuals, educational videos, asthma-related models and devices and first aid kits (http://triplea.asthma.org.au). Trained health-workers provide the initial training of the peer leaders and facilitate the steps of the programme.

The programme content covers management of asthma exacerbations, resisting pressure to smoke and asthma medication and triggers [17]. Programme delivery occurs through interactive teaching and learning activities, including role-play and group discussion, all of which are more effective than traditional didactic education for adolescents [18]. Importantly, Triple A is grounded in universally applicable theoretical concepts including peer leadership, self-efficacy [19] and empowerment [20,21], suggesting its potential for use in different cultural contexts.

Methods

Subjects

A private school for girls (n = 240) in a large city in northern Jordan, which is the second largest in the district was selected. Using the Triple A peer-training cascade, junior students from years 7 and 8 and more senior students from years 10 and 11 attending regular school classes were invited to participate.

Intervention

Prior to the programme, the lead researcher, who is a nurse in Jordan, received training from the developer of the Triple A programme in Australia. She then trained 2 research assistants from Jordan to co-facilitate the peer leaders’ training workshop. As the Triple A programme is delivered in English, this modification to the original programme was important to provide bilingual and bicultural health care providers who were familiar with the beliefs and practices of Jordanian adolescents and their families. Two teachers who were nominated by the school principal to act as liaisons were informed of the Triple A programme content and resources.

The Triple A programme was then implemented in 3 steps as outlined in Figure 1. Volunteers recruited to serve as asthma peer leaders were trained (step 1) to deliver asthma lessons to younger peers in 3 sessions. These sessions, conducted in both Arabic and English, focused on asthma knowledge, empowerment and leadership and participants received a standardized manual. Following this training, the asthma peer leaders conducted 3 asthma lessons for year 10 students (step 2). In steps 1 and 2, activities were introduced in English and then explained in Arabic to make sure that all health messages in all activities were understood by all students. Volunteers from year 10 developed key asthma and smoking messages to present to the school community (step 3) using songs, drama, poems and short acts; these messages were delivered in a 30-minute school assembly. Student participation involved a total of 14 hours over a 6-day period to deliver the programme: 10 hours for asthma peer leaders, 3 hours for year 10 students, and 30 minutes for the whole school.

Instruments

Asthma peer leaders’ perceptions of the programme effectiveness and acceptability were assessed by 3 open-ended questions in English developed for the original Triple A programme trial [16,22]. Students wrote their feedback in Arabic. Acceptability was also assessed by a focus group discussion conducted in Arabic with year 7 and 8 students, following the school assembly. Feasibility was assessed by the level of support, voluntary involvement and commitment of the teachers and students and recorded in field notes by the first author.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ministry of Education in Jordan and the ethics committee of the University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. As gaining parental consent is not a custom in Jordan, the consent form was signed by the students, a variation approved by both countries’ ethics committees.

Data analysis

Students’ responses to the evaluation questions and the researchers’ notes from the focus group were collated by the first and second authors and independently sorted into themes labelled using the students’ actual words.

Results

Staff and students enthusiastically participated in all steps of the programme. The school principal was supportive and committed to implementing the Triple A programme in her school, as were the 2 nominated teachers. The programme was widely accepted by the students with many volunteering to participate (Figure 1).

Programme evaluation

Evaluations were completed by the 10 asthma peer leaders (83%) following the training workshop and by 24 year-10 students (73%) following the lessons delivered by the asthma peer leaders. As the evaluation of both the workshop and lessons revealed very similar themes they have been combined to avoid repetition. The themes, outlined in Table 1, reflect improved awareness and knowledge of asthma and a positive reception to the peer-led approach among participating students.

As shown in Table 2, year 7 and 8 students gained increased awareness of and positive attitudes and beliefs towards asthma, as well as better understanding of the harmful effects of smoking. The researcher noted that the year 10 volunteers were confident and seemed to enjoy giving the performances, which were presented using poetry, drama, posters and songs. The information presented by the peer leaders in English was correct and Arabic words were appropriately substituted for English words when needed. Overall, the positive effects of Triple A noted in these evaluations were consistent with the overall educational aims and objectives of Triple A as illustrated in Table 3.

Discussion

A modified peer education programme about asthma was well-received, feasible and acceptable to students and staff in a Jordanian high school. Participating students, including peer leaders, gained a better understanding of asthma and its related management and the negative effects of smoking and developed more acceptance and support for students with asthma. This is the first study to test an English language peer-led school-based education programme in an Eastern Mediterranean region setting, The positive results of this study suggests that the peer education programmes can be successfully adapted and implemented in different contexts and that the influence of peers is powerful and potentially universal.

An unexpected benefit of the programme was students’ interest and increased confidence in using spoken English. This is promising for further dissemination of the programme in schools where the level of English may be lower and in other non-English speaking countries where English is a school subject. However, it is essential that bilingual local health workers are involved in the programme adaptation and implementation, and that participants’ level of English is considered and modifications made as necessary.

The positive reception for the peer-led approach is consistent with previous studies [22] and hypotheses about the importance of peer role modelling [23], and provides further support for the value of peer education programmes. The study findings also support the use of programme activities based on general theories and principles [19,20], and indicate that similar interventions should be theoretically based. In practical terms, the findings also point to the success of standardized training resources and training workshops, consistent with other research [24]. Having the programme conducted by bilingual health workers was also important [25–27], and the support and voluntary participation of the school principal and teachers was critical for programme delivery. Gaining school support and commitment required the lead researcher to explain the programme and the need for it.

A limitation of the study was that it was conducted in a single, private, girls’ school and so the findings may not be generalizable, particularly to schools where English is not studied extensively. Quantitative evaluation and longer-term assessment of the programme impact are essential, but were beyond the scope of the study. The lack of quantitative evaluation precludes a definitive assessment of the effect of the programme on adolescent knowledge and health outcomes, but the positive findings from the qualitative evaluation of feasibility and acceptability point to the suitability of undertaking a larger study with a quantitative evaluation component.

Conclusion

A peer-led asthma education programme developed in Australia was feasible and acceptable in the Jordanian cultural and linguistic context. These findings provide a positive message about the use of peer education, as well as support for further testing of the Triple A programme in Jordan. A randomized controlled trial is being conducted to examine the effect of the adapted programme on specific outcomes, including asthma-related quality of life and knowledge, and the ability to resist smoking.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participating students for their involvement and the school staff for their support. This work was supported by Jordan University of Science and Technology by a scholarship for the first author and provision of research assistant support.

References

- Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2005, 9:69–74.

- Paus T. Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2005, 9:60–68.

- Green J. Peer education. Promotion & Education, 2001, 8:65–68.

- Turner G. Peer support and young people’s health. Journal of Adolescence, 1999, 22:567–572.

- Bament D. Peer education literature review. Adelaide, South Australian Community Health Research Unit, 2001.

- Cohall AT et al. Overheard in the halls: what adolescents are saying, and what teachers are hearing, about health issues. Journal of School Health, 2007, 77:344–350.

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. Adolescent social networks: School, demographic, and longitudinal considerations. Journal of Adolescent Research, 1996, 11:194–215.

- Ennett ST et al. School and neighborhood characteristics associated with school rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1997, 38:55–71.

- McCann DC et al. A controlled trial of a school-based intervention to improve asthma management. European Respiratory Journal, 2006, 27:921–928.

- Valeros L, Kieckhefer G, Patterson D. Traditional asthma education for adolescents. Journal of School Health, 2001, 71:117–119.

- Cuijpers P. Effective ingredients of school-based drug prevention programs. A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors, 2002, 27:1009–1023.

- Mellanby AR, Rees JB, Tripp JH. Peer-led and adult-led school health education: a critical review of available comparative research. Health Education Research, 2000, 15:533–545.

- Sawyer SM, Shah S. Improving asthma outcomes in harder-to-reach populations: challenges for clinical and community interventions. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 2004, 5:207–213.

- Abu-Ekteish F, Otoom S, Shehabi I. Prevalence of asthma in Jordan: comparison between Bedouins and urban schoolchildren using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood phase III protocol. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings, 2009, 30:181–185.

- Al-Akour N, Khader YS. Quality of life in Jordanian children with asthma. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 2008, 14:418–426.

- Shah S et al. Effect of peer led programme for asthma education in adolescents: cluster randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 2001, 322:583–585.

- Shah S, Cantwell G. Triple A program: educator’s manual. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000.

- Ochieng BMN. Adolescent health promotion: the value of being a peer leader in a health education/promotion peer education programme. Health Education Journal, 2003, 62:61–72.

- Bandura A. Recycling misconceptions of perceived self-efficacy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1984, 8:231–255.

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, Continuum Books, 1970.

- Freire P, Reynolds R. Pedagogy of the city. New York, Continuum Books, 1993.

- Shah S, Mamoon HA, Gibson PG. Peer-led asthma education for adolescents: development and formative evaluation. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 1998, 8:177–182.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 1977, 84:191–215.

- Story M et al. Peer-led, school-based nutrition education for young adolescents: feasibility and process evaluation of the TEENS study. Journal of School Health, 2002, 72:121–127.

- Bronheim S, Sockalingam S, National Center for Cultural Competence. A guide to choosing and adapting culturally and linguistically competent health promotion materials. Washington DC, National Center for Cultural Competence, 2003.

- Simmons R et al. Health education and cultural diversity in the health care setting: tips for the practitioner. Health Promotion Practice, 2002, 3:8–11.

- Boyer CB et al. Youth united through health education: community-level, peer-led outreach to increase awareness and improve noninvasive sexually transmitted infection screening in urban African American youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2007, 40:499–505.

Volume 31, number 5 May 2025

Volume 31, number 5 May 2025 WHO Bulletin

WHO Bulletin Pan American Journal of Public Health

Pan American Journal of Public Health The WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health (WHO SEAJPH)

The WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health (WHO SEAJPH)