F. Rabbani,1,2 F. Qureshi2 and N. Rizvi2

ABSTRACT There is no adequate profile of domestic violence in Pakistan although this issue is frequently highlighted by the media. This case study used qualitative and quantitative methods to explore the nature and forms of domestic violence, circumstances, impact and coping mechanisms amongst selected women victims in Karachi. Violence was a continuum: all the women reported verbal abuse, often escalating into physical, emotional, sexual and economic abuse. The husband was the most common perpetrator. Women suffered in silence due to sociocultural norms, misinterpretation of religious beliefs, subordinate status, economic dependence and lack of legal redress. Besides short-term local measures, public policy informed by correct interpretation of religion can bring about a change in prevailing societal norms.

La violence familiale : une étude de cas à Karachi (Pakistan)

RÉSUMÉ Il n’est pas possible de dresser un tableau exact de la violence familiale au Pakistan, même si les médias accordent souvent une large place à ce problème. Dans le cadre de cette étude de cas, nous avons appliqué des méthodes qualitatives et quantitatives pour examiner la nature de la violence familiale et les formes qu’elle revêt, les circonstances dans lesquelles elle se produit, ses effets ainsi que les mécanismes d’adaptation chez un certain nombre de femmes victimes de violence à Karachi. La violence était omniprésente : toutes les femmes indiquaient qu’elles faisaient l’objet de harcèlement verbal, qui dégénérait souvent en violence physique, émotionnelle, sexuelle et économique. Le plus souvent, c’est le mari qui était l’auteur des violences. Les femmes souffraient en silence en raison des normes socioculturelles, d’une interprétation erronée des concepts religieux, de leur statut de subordonnées, de leur dépendance économique et de l’absence de réparation en justice. Outre des mesures locales à court terme, une politique gouvernementale inspirée par une interprétation correcte de la religion peut amener un changement dans les normes sociétales existantes.

1Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (Correspondence to F. Rabbani:

2Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

Received: 13/07/05; accepted: 09/03/06

EMHJ, 2008, 14(2): 415-426

Introduction

Domestic violence (a proportion of the total violence against women) may be defined as any act committed within the family by a family member, or behaviour that results in physical harm or psychological injury to an intimate partner or other member of the family [1,2]. Disparity in the definition and determinants of domestic violence across cultures makes comparative studies difficult. Globally, domestic violence and rape constitute 5% of the health burden for women in their reproductive years [2] and has been reported from countries as varied as the United States of America, Chile, Peru, Egypt, Papua New Guinea, India (dowry deaths), China (female infanticide) and Bangladesh [1–8]. In a study conducted in Pakistan, domestic violence emerged as an important public health concern, with 100% of men respondents admitting to verbal abuse, 33% to physical abuse and 78% to sexual abuse of their wives [9].

The social causes of domestic violence in developing countries stem from economic backwardness, insufficient protection by laws, low educational levels, a patriarchal society and the low social status of women [10–12]. In Pakistan, men are generally considered superior and women seen as chattels who are expected to be dutiful to husbands and children, especially as they lack economic security [13].

Apart from the physical dangers, the psychosocial consequences of violence are also grave. Victims are more likely to use marijuana and alcohol for coping, to have depression and to attempt suicide [14–16]. Domestic violence endangers women’s autonomy and social stability and drains their emotional strength and self-esteem. Frequently, there is an associated negative impact on women’s reproductive health [17].

For the woman, strategies for dealing with violence range from leaving the aggressor, accepting the violence or resorting to self-defence [11]. Recent studies are focusing on helping the victims deal with the consequences of partner violence [18].

Pakistan lags far behind most developing countries in women’s health and gender equity. The sex ratio is one of the most unfavourable to women in the world, a result of excess female mortality during childhood and childbearing. Lack of mobility, decision-making power and income, as well as prohibitions against seeking care from male providers, present serious constraints to women’s ability to use the limited services that are available [19].

Uneducated, tired from repeated childbearing and economically dependent, women are also vulnerable to crimes and violence. The latter can be attributed to different cultural, sociological and political factors. State legislations (not always bound by Islamic law) favour the traditional cultural bias against women with regards to age at marriage, choice of husband, rights to inheritance, divorce, etc. [20]. Poverty, ignorance, economic dependence and tradition exacerbate the situation. Pakistan’s national plan of action specifically recommends “...measures to deter and address incidence of domestic and sexual violence” [21].

The popular press has also highlighted issues related to this in the sociocultural perspective of Pakistani society. However, there is little local scientific evidence available in this area. Studies from other South Asian countries, with which Pakistan shares many sociocultural traditions, indicate that domestic violence is a grave problem in the region [7]. Except for one or two preliminary studies directly reporting on the issue [9,17], we did not find any published population data on domestic violence in Pakistan. Another study has indirectly probed the issue, looking at Pakistani obstetricians’ knowledge of the prevalence of domestic violence in clinical practice and their attitudes towards instituting screening protocols during routine antenatal care [22].

Our study therefore proposed an initial investigation of the nature and forms of domestic violence, the surrounding circumstances, the impact on victims and coping mechanisms used by victims in Karachi. The ultimate aim was to establish hypotheses for larger studies to establish the extent of the problem and cause–effect relationships so that appropriate preventive strategies can be recommended.

Methods

It is difficult to obtain reliable and accurate information through a representative large household survey on a sensitive and illdefined issue such as domestic violence. We therefore used the case study approach as a form of empirical enquiry. A case study investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context and is especially of use where the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context are not clearly defined [23]. Multiple sources of evidence are usually relied upon, with the data converging through triangulation. This approach benefits from the prior development of theoretical propositions, in this case the Duluth model [24]. This is a classic model of behaviour characterized by the misuse of power and control by one person over another. Initially conducted as part of an experiment in Duluth, United States of America, this programme has now become a model for use by other intervention projects.

Using a mix of qualitative and quantitative techniques, data collection was conducted in Karachi, Pakistan from 1999– 2001 by the Department of Community Health Sciences at Aga Khan University. Initially domestic violence was studied by interviews with key informants and opinion leaders and through focus group discussions (FGDs). Eight key informant interviews were done with people who were knowledgeable health care providers, opinion leaders and social workers. FGDs were used to gather knowledge regarding community perceptions of domestic violence, the magnitude of the problem, types of violence, causes, impact, coping strategies and the role of community leaders and the media. Of the 13 FGDs completed, 8 were with women and 5 with men. These discussions were conducted with representatives from the major ethnic groups of Pakistan (Balochis, Pathans, Punjabis, Sindhis and Urdu speaking people whose parents migrated from India). Both key informant interviews and FGDs lasted for about 2 hours each. FGDs were audiotaped, group dynamics were observed and notes were taken and transcribed later. Confidentiality was assured and external distractions were minimized. FGDs were organized either at the homes of community activists or at the Department of Community Health Sciences.

Key informant interviews and FGDs were edited, translated (where necessary) and transcribed by the team. Information from key informants and FGDs was used to develop a semistructured questionnaire with both closedand open-ended questions. As it was not practical to conduct a random survey on this issue, we used convenience sampling to identify 108 respondents (women victims) who had reported experiencing any type of violence from husbands and/or other family members and administered this questionnaire to them. These victims were identified with the support of human rights organizations, social activists and by field staff of the Department of Community Health Sciences working in Aga Khan University’s community-based health and development programmes. The majority of interviews (75) were conducted at the homes of the victims, community volunteers or activists, and community health centres. Urdu (the national language, understood by all) was used for interviews. The open-ended questions in the questionnaire were later back-translated into English and a complete profile of each case was written by the first 2 authors. This helped to develop detailed narrative accounts of circumstances surrounding the violent episodes and to highlight emergent themes. This structured questionnaire obtained information on key sociodemographic features, the perpetrator of violence, types of violence (verbal, physical, psychological or emotional, sexual, economic) and the duration, frequency, extent and severity of violence. The circumstances or events leading up to the occurrence, the impact and outcomes (adjustment, management, coping) were also explored.

Institutional ethical approval was obtained. The purpose of the study was explained and verbal consent taken from respondents. The latter were free to terminate the interview at will. All efforts were made to ensure the privacy, confidentiality and security of the interviewee. Data from these 108 cases were coded, edited and cleaned using Fox Pro version 2.6, then doubleentered in Epi-Info, version 6.04C. The error rate was under 1%.

Statement of consent to participate This is to verify that all persons on whom the research has been carried out have given their informed verbal consent prior to the start of the interviews. No information has been revealed in this study linking results to individual respondents. Moreover the Community Management Teams in all field sites of Urban Health Program, Dept of CHS, Aga Khan University, Karachi, consented to conduct of focus group discussions either on or off the field premises. The key informants were experts in the field and were contacted by appointment for their time to contribute their views on this study.

Results

There was a great concurrence of views obtained from the 3 techniques: key informant interviews, FGDs and case interviews. The team developed types and categories of abuse using the definitions of domestic violence quoted earlier. We also consulted the Duluth model of power and control to classify types of abuse [24]. Of the 108 women interviewed, 102 (94%) were ever-married while there were 6 women in our sample who had never married and were single. Of the ever-married women, 61 were currently married, 21 divorced (a relatively high proportion compared to the prevailing norm as these were specially selected cases), 17 separated and 3 widowed at the time of the interview. The mean age of respondents was 33 years. As judged by the ownership of assets, most families were reasonably well off with 64% owning a television and 69% reporting living in a family-owned house. Only 56% of the women were literate.

Nature and forms of domestic violence

Abuse was classified as “verbal” when there was use of bad or abusive language, loud tone, bullying, threatening (oral threats, intimidating behaviour, gestures, throwing or smashing things). All women (100%) reported being abused verbally and 58% reported psychological abuse (such as suspected or actual infidelity by the husband, emotional blackmail by the perpetrator, character assassination, social isolation or perceived neglect of basic needs by the husband) in combination with other abuse types. Physical violence occurred generally in combination with verbal and/or psychological abuse and was reported by 76% of women. It ranged from slapping, pulling hair, pushing or shoving, grabbing, hitting with an object and twisting the arms (mild forms) to kicking, punching, suffocating, intentional burns, hitting that resulted in fracture or injury to a vital organ (severe forms). Physical injury during pregnancy was also reported. Overall 12% of women reported some form of sexual abuse, nearly always in combination with other forms of violence. This included rape, forced prostitution and forced intercourse in marriage. On the whole, 39% women suffered some form of economic control. This included withholding money from the victim or refusal to meet household expenses, control of the woman’s wages or assets and stealing valuable assets such as personal jewellery or land, etc. Economic abuse also always occurred in combination with other forms of violence.

Perpetrators and frequency of abuse The husband was the most common perpetrator (88%) of violence, most often in combination with other members of his family. However in 58% of cases the husband alone was involved. Among the other perpetrators, the mother-in-law (15%) was the next most common abuser, in concert with her daughter(s) or other son(s). Mothers-in-law provoked or initiated violence against the victim by complaining to the husband. The mean duration of abuse was 11 years. Frequent abuse was defined as occurring every month, every week or every day. This was reported in 92% of cases.

Women’s response to abuse

In answer to a question as to what women did in response to abuse, individual victims reported a range of coping strategies. Most victims used more than one strategy. Initially most (90%) kept quiet or used strategies to minimize provoking factors; 58% resisted and either answered back or fought back; 56% talked to someone; 28% returned to their parent’s house, leaving the husband either temporarily or conditionally; 26% initiated some legal action for separation, divorce or for recovery of property; 17% reported that they went visit a friend or relative just to get out of the home environment and tension. Women actively reduced occasions that resulted in abuse: “I don’t ask for money anymore”; “I have found a job”; “I keep quiet now till he has cooled down, and express my views later”. Those who had poor family support systems (parents dead or very poor) were more likely to accept the situation and continue to live with the husband rather than return to their parental home.

Consequences of abuse

Physical abuse was reported by over two thirds of the women. The most common site of injuries was head, neck, face and arms. Bruises, aches, pains and local swelling were commonly reported, and victims resorted to home remedies and selftreatment. Less commonly there were cuts or more grave injuries such as fractures that required medical assistance. There was one case of burns (reported as unintentional injury to police) and the woman later died in hospital.

All forms of abuse had a psychological impact. Depression escalated into anger.

There were 10 suicide attempts by 9 women (6 ingested tranquillizers or insecticide, and 3 poured kerosene or petrol over themselves and set that on fire but were subsequently saved); 3 others reported suicidal thoughts. Women reported that they did struggle and fight back, but over time they were emotionally exhausted and their attitude became fatalistic. They blamed “fate” for their circumstances and expressed a sense of helplessness and despair.

No male victims of domestic violence were identified in this sample, but men in FGDs pointed out that marital discord definitely has a negative emotional impact on men too. Directly or indirectly, children were also victims. Interviewed victims reported a great deal of concern for and impact on their offspring.

Discussion

In Arab and Islamic countries, domestic violence is not yet considered a major concern, despite its increasing frequency and serious consequences. Surveys in Egypt, Palestine, Israel and Tunisia show that at least 1 out of 3 women is beaten by her husband [25]. The indifference to this type of violence stems from attitudes that domestic violence is a private matter and, usually, a justifiable response to misbehaviour on the part of the wife. This is in contrast to Islamic teachings. Marriage in Islam is a sacred act as stated in the Quran, “And one of His signs is that He hath created for you mates of your own species that ye may find comfort and rest in their company; and (with that end in view) hath put between you love and tenderness” (30:21). The Quran has clearly stated that women have rights even as they have duties, according to what is equitable, but men are a degree above them (2:228). The slight superiority is to be read in conjunction with another passage which states among other things, that men are trustees, guardians and protectors of women because men excel in physical strength and because men expend their means (4:34). Islam emphasizes that a person’s status in society is determined by their deeds and not by gender. In early Islam, women excelled in scholarship, medicine and warfare. However, with the passage of time, based on the Islamic teaching of tolerance and respect for other religions, the area that now comprises Pakistan absorbed much from the prevalent local cultures (Hinduism, Buddhism) and changed its view of women’s status [26]. Ironically, selective excerpts from the Quran are widely misinterpreted without regard to context in order to justify men’s supremacy over women. Polygamy (which is allowed in Islam, provided the husband is able to treat all wives with equality and justice) has also often been misquoted and used to promote promiscuity. Also women’s religious rights to remarry and divorce are disapproved by this society.

This discrimination against women is neither a new phenomenon nor restricted to Pakistan. From many perspectives women in South Asia (particularly Pakistan, India and Bangladesh) find themselves in subordinate positions to men and are socially, culturally and economically dependent on them [27]. In these Asian countries with agriculture-based economies, the historical tribal feudal system and patriarchal structures accord women a secondary role. As in other Muslim societies [28], in Pakistan women’s only close relationship with an unrelated male is with their husband. In Pakistan women are excluded from monetary transactions in markets for the goods they produce. Education for girls is thought to “spoil” and distract them from attention to household tasks. There is no value placed on girls attaining more than a primary education [29]. A girl child is considered only a “visitor” in the house where she is born and that eventually she has to go to her “real” or marital home. These cultural perceptions are related to the strong image of women as dependent/private wives and mothers [30]. In South Asian society women themselves consider that they are incomplete, insecure, ineffective and inefficient without males [26]. On the basis of this concept, the male member is dominant in society and the female members are expected to be docile. Men are able to exploit women’s weaknesses. In fact, every aspect of women’s lives is more highly controlled than for their male counterparts. It has resulted in a society in which women endure discrimination and violence simply because they are women.

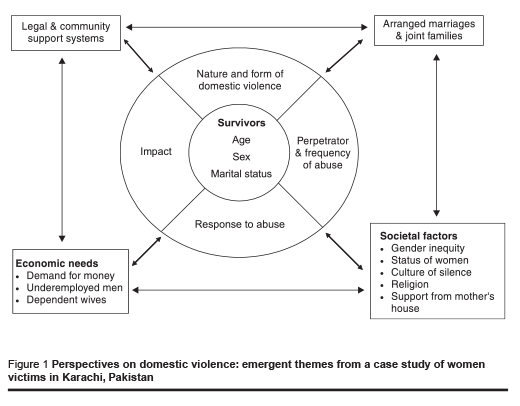

Given this cultural and religious context from Pakistan and other countries in the region, and based on various sources of data in our study, we present here a thematic analysis of circumstances surrounding domestic violence (Figure 1).

Thematic analysis

Violence is a continuum

Based on data from our study, violence seems to follow a sequential pattern. The sequence appears to start with verbal abuse, escalating into anger and then exploding into all forms of violence. Just as reported elsewhere [28], shouting or yelling is quite culturally acceptable. In this study, isolated episodes of violence were uncommon. Generally violence occurred in cycles: abuse was followed by a quiescent period lasting for various durations before restarting.

Arranged marriages and family formation patterns

All the customs governing marriage in Pakistan are highly male-oriented. In arranged marriages—the most common kind in Pakistan and in this sample too—and cousin marriages at a relatively young age, it is usually the husband’s family who sends out the proposal for marriage to the prospective bride’s parents. The feelings and preferences of the couple concerned are often not taken into consideration. The bride has to move to live in the husband’s home and is expected to make adjustments while the bridegroom continues to live in his ancestral home. Reporting on gender relations in South Asia, another study reports that the functioning of the “family unit” requires the subsuming of women’s interests and ignores the real-life experiences of women. It further adds that the notion of “family” is constantly undergoing change [31]. The majority of our victims lived in joint families with interference from in-laws. Usually minor differences and arguments between the couple exploded into various forms of violence upon incitement by in-laws. Victims reported that such a family system acts “like a matchstick which evokes a fire”.

Lack of economic resources

Arguments begin with verbal exchanges triggered by demands for money. At the time of our study, the average monthly household income in Pakistan was US$ 137 [32]. In this study many arguments began about the needs of the family and a lack of resources, and who decides how to use the resources. The husband usually either keeps the income himself or gives it to his mother. The majority of men are financially insecure with demands for money increasing with time. One woman victim said that “when a man cannot establish his authority intellectually or economically, he may do this physically”. This is in concurrence with theories that explain the prevalence and occurrence of violence. It is reported that males are considered as macho beings and aggression is an important trait. If men sense a loss of control—for example, if the woman somehow gets stronger educationally or economically—they try to regain control by battering or other forms of violence until she surrenders [26].

Declining social support from maternal home

After the death of parents, especially the mother, it is customary in Pakistani society for sons to inhabit the maternal home. It was observed in our study that the strong social support and integrated family system weakens with time and sisters-in-law (brother’s wives) do not usually welcome back the victim and her children if they try to return on the grounds that the latter has already had her share of the family inheritance in the form of a dowry at marriage and is an added burden to the family now. Brothers neither support financially nor accept the divorced sisters to work outside for wages as it would damage the family honour. As one woman in the study said “what choices do we have?” Thus the woman victim of violence has little option except to continue in the current relationship.

Lack of legal support system

In Islam, guardianship (especially for minors) for the purpose of marriage is allowed because of the necessity for a proper and suitable match, which may not always be available [33]. Guardianship extends to the father and grandfather and in their absence other relations. However, again this guardianship was reportedly misused (although few women victims in this study reported this) to marry women without respecting their choice or taking their consent. Later it was difficult to break out of the matrimonial bond because of the social stigma attached to divorce. Victims often said “this does not happen in our family”. The victims in this study stayed in abusive relationships, were reluctant to initiate legal action and even returned to their husbands because of their children. Khula or request for dissolution of marriage by wife, although allowed by religion, is comparatively rare. As one of our victims reported “if there is anyone to be blamed for breaking the bond it is quite usual that a fault is found in the woman; therefore I bear the violence”. The judicial system is not conducive to taking quick decisions in issues related to matrimony as they are publicly regarded as personal matters.

Woman viewed as an object

Besides complaints about the inability of a wife to take good care of household matters, her physical appearance—for example, not being up to accepted standards of beauty—was also the subject of abuse. In one of the FGDs with men it was pointed out that inspired by the media, young men usually demand a smart, pretty and dutiful wife, and when this expectation is not met they try to find fault in trivial matters. This often leads to arguments and evokes violent masculine behaviour.

Unmet needs for sex

Although not overtly reported, there were arguments about unmet needs for sex. A few women also reported undesired marital intercourse. Alcohol and substance abuse were not reported to be major triggers of sexual violence. However, they were reported in combination with other factors listed above, especially among a particular periurban community.

Culture of acceptance and silence

Women “accepted” abuse by husbands as normative behaviour, and believed that if adjustments have to be made, it is the women’s role to make the change. Other studies have also reported that victims may show little or no resistance so as to minimize the renewed aggression or injuries [28]. The women interviewed were very reluctant to share deeply personal and private issues of abuse with anyone, possibly because of shame (“people just laugh”), or helplessness (“what can anyone do anyway?”), and fear of causing distress to their families. The first ones to hear are probably close female friends or mothers but there is great reluctance to take any action.

Limitations

The cases in our study were specially selected to identify the nature and forms of domestic violence, circumstances around violent episodes and the impact and coping mechanisms used by victims. This case study was part of an initial assessment to generate hypotheses about possible determinants and factors associated with domestic violence. It is important to keep in mind that the study presents reported data of perceived abuse by the respondents only. No corroborating information was obtained from other sources or the husbands, but often neighbours, family or community members were aware of the discord and had identified victims for the research team.

Recommendations

In the absence of relevant appropriate information, population-based epidemiological studies should explore culturally appropriate means of identifying and responding to abused women in resource-poor settings such as Pakistan. The community health houses in the Islamic Republic of Iran, panchayat in India and union parishads in Bangladesh act as the focal point for facilities, personnel and service delivery and offer empowerment initiatives [19]. Short-term efforts in Pakistan could include community-based health and family planning clinics to put abused women in contact with support services, since they have ongoing contact with the population at risk. Proper training and protocols are required to sensitize lady health workers—who have access to households under the government programme—to the issue of gender-based violence. A focus on community support groups and gender sensitization workshops is required. Counselling support and advocacy, as well as the mass media, need to be organized to address the issue.

Conclusion

Violence against women is not inevitable. The success of efforts to combat violence against women depends on a change in prevailing societal norms and correct interpretation and communication of the rights conferred to women by Islam. As long as society accepts the dominant masculine role and tolerates violent treatment of women, domestic violence will remain a problem.

Moreover, domestic violence should not be seen as private; it is a social problem whose resolution will require public policies, including appropriate legislation and protection of women’s rights.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to the World Health Organization Centre for Health Development, Kobe, Japan for providing the funds to the principal investigator, Dr Asma Fozia Qureshi, to conduct this study under project ID number HQ/99/010793 (later reported in the WHO Centre for Health Development, Kobe, Japan’s International Public Health special edition as a part of a pilot research project on urban violence and health in 2001: ISBN 3-932136-82-9). We are thankful to our research assistants, Ms Fatima Sajan, Ms Anila Zaheeruddin and Zia Sultana, for assisting in conducting and transcribing the interviews. Ms Kausar S Khan, Drs Anwar Islam, Parvez Nayani and Riffat Zaman worked in the faculty research group. We thank the victim respondents for sharing their life circumstances with us and last but not least we must acknowledge our key informants, participants and staff of the Urban Health Programme, the Department of Community Health Sciences at Aga Khan University, and community activists for participating in this study.

References

- Tjaden P. What is violence against women? Defining and measuring the problem: a response to Dean Kilpatrick. Journal of interpersonal violence, 2004, 19(11):1244–51.

- Krug EG et al. eds. World report on violence and health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002.

- Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M. A global overview of gender-based violence. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics, 2002, 78(Suppl. 1):S5–14.

- Heise LL et al. Violence against women: a neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Social science & medicine, 1994, 39(9):1165–79.

- The world’s women 2000: trends and statistics. New York, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2000.

- Anderson JW, Moore M. Born oppressed: women in the developing world face cradle-to-grave discrimination. Washington post, 14 February 1993, Section A:1.

- Bates ML et al. Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International family planning perspectives, 2004, 30(4):190–9.

- Parish WL et al. Intimate partner violence in China: national prevalence, risk factors and associated health problems. International family planning perspectives, 2004, 30(4):174–81.

- Shaikh MA. Domestic violence against women—perspective from Pakistan. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 2000, 50(9):312–4.

- Xu X et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for intimate partner violence in China. American journal of public health, 2005, 95(1):78–85.

- Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Social science & medicine, 2002, 55(9):1603–17.

- Ellsberg M et al. Candies in hell: women’s experiences of violence in Nicaragua. Social science & medicine, 2000, 51(11):1595–610.

- Miller BD. Daughter neglect, women’s work, and marriage: Pakistan and Bangladesh compared. Medical anthropology, 1984, 8(2):109–26.

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Raj A. Adverse consequences of intimate partner abuse among women in non-urban domestic violence shelters. American journal of preventive medicine, 2000, 19(4):270–5.

- Otoo-Oyortey N. A battered woman needs more than biological help. IPPF medical bulletin, 1997, 31(3):5–6.

- Hou WL, Wang HH, Chung HH. Domestic violence against women in Taiwan: their life-threatening situations, post-traumatic responses, and psycho-physiological symptoms. An interview study. International journal of nursing studies, 2005, 42(6):629–36.

- Fikree FF, Bhatti LI. Domestic violence and health of Pakistani women. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics, 1999, 65(2):195–201.

- Arriaga XB, Capezza NM. Targets of partner violence: the importance of understanding coping trajectories. Journal of interpersonal violence, 2005, 20(1):89–99.

- Tinker AG. Improving women’s health in Pakistan. Human development network. Health, nutrition and population series. Washington DC, World Bank, 1998.

- Crime or custom? Violence against women in Pakistan. New York, Human Rights Watch, 1999.

- Nishtar S et al. The national action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases and health promotion in Pakistan—prelude and finale. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 2004, 54(12 Suppl. 3):S1–8.

- Fikree FF et al. Pakistani obstetricians’ recognition of and attitude towards domestic violence screening. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics, 2004, 87(1):59–65.

- Yin RK, ed. Case study research: design and methods, 3rd ed. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Volume 5. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications, 2002.

- Pence E, Paymar M. Education groups for men who batter: the Duluth model. New York, Springer, 1993.

- Douki S et al. Violence against women in Arab and Islamic countries. Archives of women’s mental health, 2003, 6(3):165– 71.

- Niaz U. Violence against women in South Asian countries. Archives of women’s mental health, 2003, 6:173–84.

- Changing gender relations in the household. In: Naryan D et al. Voices of the poor: can anyone hear us? New York, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Ahmed AM, Elmardi AE. A study of domestic violence among women attending a medical centre in Sudan. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2005, 11(1/2):164–74.

- Ibraz TS, Fatima A. Uneducated and unhealthy: the plight of women in Pakistan. Pakistan development review, 1993, 32(4):905–13.

- Ibraz TS. Cultural perceptions and the productive roles of rural Pakistani women. Pakistan development review, 1992, 31(4 Pt. 2):1293–304.

- Mukhopadhyay M. Gender relations, development practice and “culture”. Gender and development, 1995, 3(1):13–8.

- Household integrated economic survey 1998–99. Islamabad, Statistics Division, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistics, Government of Pakistan, 1999.

- Husain A. Muslim personal law: an exposition. Nawatu Ulama, Lucknow, India, All India Personal Law Board, Camp Office, 1989 (ASIN:B0007C24F0).