R.E. Morris,1 G.M. Gillespie,2 F. Al Za’abi,1 B. Al Rashed1 and B.E. Al Mahmeed1

التخطيط الاستـراتيجي الجازم لصحة الفم في الكويت: عَقْدٌ من النجاحات بعد الحرب

روبرت موريس، جورج جلسبي، فاطمة الزعابي، بدر الراشد، بدر عيدان المحميد

الخلاصـة: يناقش الباحثون التخطيط الاستـراتيجي وتنفيذ برامج رعاية صحة الفم والوقاية من أمراضه بعد حرب الخليج 1990/1991. وقد تمثَّلت الفكرة الأساسية في تطوير سُبُل إتاحة الرعاية والوقاية من الأمراض لجميع الأطفال الكويتيـِّين في رياض الأطفال والمدارس الابتدائية الحكومية، واستبعاد التـركيز على أعمال خلع وتـرميم الأسنان. وكانت الموارد قد عادت إلى مستويات ما قبل الحرب، ثم ازدادت. فأنشئت برامج وقائية تغطي نحو 000 150 طفل، كما زيدت الاعتمادات الوقائية من 7% إلى 20% من ميزانية صحة الفم، وزادت أيضاً نسبة أطباء الأسنان المهتمِّين بالوقاية من 9.7% إلى 28% من مجموع أطباء الأسنان. وأمكن وقف التـزايُد في اتجاهات التسوس، أو خفضها بنسبة بَلَغَتْ 36.8%. كما زادت نسبة الأسنان اللبنية الخالية من التسوس لدى الأطفال بمقدار 37.6%، وفي الأسنان الدائمة بمقدار 27%. وتـُوِّج ذلك بإنشاء كلية لطب الأسنان.

ABSTRACT: Strategic planning and implementation of oral health care and disease prevention programmes after the 1990/91 Gulf war are discussed. The key concept was to develop access to care and disease prevention for all Kuwaiti children in government kindergarten/primary schools and to eliminate emphasis on extractions and restorations. Resources were restored to pre-war levels and then increased. Prevention programmes for 150 000 children were established. Prevention funds increased from 7% to 20% of the oral health budget. Prevention-based dentists increased from 9.7% to 28.0% of staff. Rising caries trends were stabilized or reduced by up to 36.8%. Percentage of caries-free primary dentition in children increased up to 37.6%, permanent dentition up to 27.0%. A dentistry school was established.

Planification stratégique agressive de la santé bucco-dentaire au Koweït : une décennie de succès après la guerre

RÉSUMÉ: Cette étude décrit la planification stratégique et la mise en oeuvre de programmes de soins bucco-dentaires et de prévention des affections bucco-dentaires à l’issue de la guerre du Golfe de 1990-1991. L’idée maîtresse était d’ouvrir l’accès aux soins et à la prévention des affections bucco-dentaires à tous les enfants koweïtiens scolarisés dans les écoles maternelles et primaires publiques, tout en cessant de privilégier extractions et restaurations dentaires. Après un premier temps de reconstitution à leur niveau d’avant‑guerre, les ressources ont été augmentées. Des programmes de prévention s’adressant à 150 000 enfants ont été mis sur pied. La part du budget de la santé bucco-dentaire dévolue à la prévention est passée de 7 % à 20 % et la proportion de dentistes consacrant leur activité à celle‑ci est passée de 9,7 % des effectifs à 28,0 %. Après une première phase de stabilisation des caries, jusque là en augmentation, on a constaté un ralentissement de la tendance de 36,8 %. Chez l’enfant, le pourcentage de dentitions indemnes de caries a augmenté, atteignant respectivement 37,6 % et 27,0 % pour les dentitions primaires et permanentes. Une école dentaire a été créée.

1Ministry of Health, Kuwait.

2University College, London and International Foundations for Health Inc., Washington DC, United States of America (Correspondence to R.E. Morris:

Received: 21/06/05; accepted: 27/11/05

EMHJ, 2008, 14(1): 216-227

Introduction

The Kuwait government provides a national health care system to all residents. Medical care is provided in a planned system at well-equipped district polyclinics, regional hospitals and central specialist hospitals, with a minimal co-payment. Oral health services are similarly provided at polyclinics, regional hospitals, specialist dental centres and at kindergarten, primary and secondary government schools. An estimated 85% of health care is provided through this national scheme, the remainder is provided by the private sector or by referral abroad.

With an economy boosted by increased oil revenues in the 1970–80s, Kuwait was able to make major investments in the health care system in human resources, training and facilities. Growth in the medical sector slowed in the late 1980s, but kept pace with population growth. The oral health sector grew throughout the decade.

The invasion by the Iraqi armed forces and subsequent war of 1990/91 devastated the Kuwait national health care system. Health and training facilities were occupied, looted and destroyed by the Iraqi army. The College of Health Sciences, for example, was used as an ammunition dump. Equipment was stolen, personnel emigrated and programmes halted. In some cases, the subsequent air assault against the Iraqis by the allied forces damaged health facilities. Much of the infrastructure and critical mass of health professional staff that had been built up in the 1980s was lost [1]. In the oral health sector alone, there was a 60% loss of dentists, a 57% loss of clinic equipment, and a complete stoppage of special projects, training and continuing education activities in the Kuwait Ministry of Health. The population was similarly affected. The estimated population of Kuwait in the late 1990s was 2.27 million, similar to 1989 (35% Kuwaitis, 65% non-Kuwaitis and stateless Bedouins). Prior to the Gulf War the population was projected to reach 3 million by the year 2000 [2].

The dentist:population ratio post-war in 1991 was 1:6700, comparable to the 1984 ratio and well below the target of 1:3000. The dental hygienist:population ratio was 1:100 000, whereas the 1990 target was 1:20 000. There were 160 clinic units functioning in October 1991, an increase from 120 clinic units immediately after the war (March 1991), or 1.33 clinic units per 10 000 population, equivalent to the 1985 level. The Centre for Advancement of Oral Health Services, which was established in 1988 to consolidate and strengthen postgraduate education and training and to provide an introductory point for new disease prevention concepts, interrupted its programmes for 3 years (1991–94). The College of Health Science 2-year oral/dental hygiene training programme was halted from August 1990 to September 1991. This programme, which commenced in 1989, graduated its first 8 students in 1992. The 2 model school health projects for children, which commenced in 1986 and 1987, were destroyed, losing their equipment and professional staff. The Forsyth School Oral Health Project (in the Capital health region) restarted care in late 1991 but with greatly reduced working hours. The Danish School Oral Health Project (Ahmadi health region) was not able to provide school-based care until late 1992, with similar minimal working hours.

After the war health planners were seriously concerned about the limited organized care and lack of follow-up for children. Surveys in Ahmadi region in 1987, in Salwa district of Kuwait city in 1993 and the national survey of schoolchildren in 1993 indicated a continuing decline in the percentage of caries-free children since 1982 (when water fluoridation was discontinued), with an increase in caries and early childhood caries (Figures 1 and 2) [3–7]. Health planners were concerned that Kuwait would not meet the World Health Organization (WHO) goal for oral health by the year 2000 for 12-year-old children of ≤ 3.0 decayed, missing and filled permanent teeth (DMFT). In the light of an identified correlation between Gulf war-related stress and higher caries index in refugees [8], it was prudent to assume that these disease rates accelerated in Kuwait as a result of the war and its after-effects, and that children in Kuwait would suffer a disproportionate degree of oral pain and disease in the immediate future.

![Figure 1 Caries trends in children in Kuwait pre- and post-war between 1982 to 1993: decayed, missing and filled deciduous teeth/surfaces or permanent teeth index (dft, dfs, DMFT). Sources: [4,20] Figure 1 Caries trends in children in Kuwait pre- and post-war between 1982 to 1993: decayed, missing and filled deciduous teeth/surfaces or permanent teeth index (dft, dfs, DMFT). Sources: [4,20]](/images/stories/emhj/vol14/01/14-1-25-f1.jpg)

![Figure 2 Oral disease in children in Al Adan region pre- and post-war: mean untreated surfaces. Source: [6] Figure 2 Oral disease in children in Al Adan region pre- and post-war: mean untreated surfaces. Source: [6]](/images/stories/emhj/vol14/01/14-1-25-f2.jpg)

Following the liberation of the country in February 1991, the Ministry of Health consolidated and activated polyclinics and hospitals, recalled staff from abroad and made emergency purchases. Dental clinics were gradually reopened and foreign dentists recruited to fill the human resource gap. Until sufficient replacements arrived, substantial limitations existed in the availability of oral health services to the general public. The first post-war government budget (1991/92) projected a deficit of Kuwaiti dinar (KD) 18 billion (1KD = US$ 3.40), the first budget deficit in modern Kuwait history. The health sector budget was KD 187 million, an improvement on a per capita basis to budgets prior to the war, but this amount was primarily for recapitalization.

There was no strategic plan in place for long-term development. Within the context of the Kuwait war, the authors, in consultation with the senior Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance management, determined that a strategic plan targeting the oral health of children was urgently required.

Aggressive strategic planning and programme implementation for post-war reconstruction of the oral health sector

Developing effective strategies to gain optimal oral health demands close attention to the key dynamic factors that define the health challenge: population demographics, levels of disease in the community, and barriers to access of services [9]. Previous developments in oral health failed to recognize the population or disease priorities of the regions of the country. Oral health care in Kuwait was almost entirely directed to treating one disease—dental caries—through extraction and repair. Kuwait is not unique. In Africa only 20% of countries have a national oral health plan [10]. In the USA, the National Institute for Dental and Cranial Facial Research has only recently completed a strategic plan [11].

Strategic planning is only one element of the overall administrative functioning of health care planning and involves an organization’s choices of its mission objectives, strategy policies, programme goals and resource allocations [12]. Implementation of strategic planning requires an analysis of the situation concerning health status, human resources, facilities and achievements of prior and traditional programmes [13]. Our situational analysis included the experience of Kuwait with previous oral health programmes and problems that required solutions or improved approaches for the delivery of services. The analysis indicated the need for a targeted approach to the prevention of oral disease and for improving the oral health of young children to achieve significant caries prevention in the absence of water fluoridation. The methodology presented a number of challenges, such as avoiding parents’ absence from the workplace, keeping children in the school environment and providing a consistently positive experience related to oral health care. The Ministry needed to make available effective oral health education and information to all sectors of the community. Staff to provide those services for children needed to be recruited locally or abroad and trained. Equipment needed to be budgeted for, acquired and installed.

The results of the situational analysis showed that any disease prevention programme needed to be implemented rapidly. It had to consider alternatives to water fluoridation for caries prevention, the provision of easy access for children to preventive care, and education and curative services (not only emergency services) from kindergarten age onward. It also had to be developed within the context of available funds and preferably to utilize personnel living within the country. The development of services would need to assure services of a high standard, utilizing cost-effective, efficacious delivery systems. The 2 children’s programmes initiated prior to the war were to be maintained and upgraded through the use of modern technology. Communication and understanding needed to be developed with the schools and collaboration implemented between the Ministries of Health, Education and Finance. An innovative approach to financing a public–private sector partnership was needed, not only to expedite the availability of funds but also to provide for the employment of dentists and auxiliaries within the Ministries’ existing regulations.

The strategic actions noted here were designed to optimize oral health in the child population at an early age; to promote and maintain oral health and hygiene through the efficient use of human resources; to optimize cooperation and collaboration; and to maximize the effective use of financial resources. A strategic national oral health plan was submitted to the government in 1992 in order to initiate the implementation process [14]. Implementing the strategic plan would move the country to “health for all/oral health” through prevention of oral disease rather than through the existing repair/extraction-based system.

The key strategies of the plan comprised the following programmatic areas:

Development of disease prevention programmes targeting at-risk populations in Kuwait, with the emphasis on schoolchildren.

Development and utilization of an expanded oral health team, including hygienists, nutritionists and health and other educators.

Appropriate professional education of Kuwaiti nationals through a national dental school, the College of Health Sciences, and the Ministry of Health.

Establishment of health research and data analysis capabilities.

Development of a national oral health promotion programme.

Development of a mass caries prevention programme utilizing fluoridated salt.

Use of international expertise to complement national resources in a public–private partnership in order to introduce modern technology and expedite implementation of the programme

In an era of reduced funding and national deficits, the management of the oral health sector was pursuing an aggressive strategy to acquire funds and to move the oral health sector to a disease prevention base, which would reduce government expenses over the long term. Given the rising oral disease rates, the failure to stabilize or reduce these diseases, and the considerable financial resources available to Kuwait during the 1970–80s, the oral health sector was considered greatly underfunded and understaffed compared with the major industrialized countries (Figures 3 and 4).

![Figure 3 Oral health expenditure as a percentage of health expenditure, Europe and Kuwait, selected years. Sources: [21,22] Figure 3 Oral health expenditure as a percentage of health expenditure, Europe and Kuwait, selected years. Sources: [21,22]](/images/stories/emhj/vol14/01/14-1-25-f3.jpg)

![Figure 4 Dentists per 100 000 population versus per capita gross national product (GNP) for Europe, North America and Kuwait, circa 1990. Sources: [22–24] Figure 4 Dentists per 100 000 population versus per capita gross national product (GNP) for Europe, North America and Kuwait, circa 1990. Sources: [22–24]](/images/stories/emhj/vol14/01/14-1-25-f4.jpg)

The primary strategy in post-war Kuwait was expanding the school-based disease prevention programmes for children, with the goal of reaching all Kuwaiti children in government kindergarten and primary public schools by the year 2000. Research results from school- and community-based children’s oral health projects in the 1980s demonstrated that more curative and preventive care services had reached a greater population, and that the caries rates had been stabilized or reduced compared to the Ministry’s traditional polyclinic programmes [15]. The cost–benefit ratio was considered superior in these projects when compared to the existing health service. The management targeted the expansion of these programmes as an area for immediate activity.

In fiscal year 1992/93, a strategic action plan was implemented and international consultants were employed to plan and develop programmes for the remaining 3 underserved health regions of Kuwait (5 regions in total). In order to achieve mass caries prevention in the absence of water fluoridation, and to complement the strategy of school-based prevention, consultants were similarly retained to plan and budget a public–private sector initiative to introduce fluoridated salt to the public [16]. This particular initiative included a situation analysis, a feasibility study, determination of urinary excretion levels of fluoride in children, costing, equipment selection, installation, introduction and a cost analysis of fluoridated salt to the public. Prior to seeking alternative financing, utilization of existing national capability and resources was considered to finance this proposal.

The 3 additional disease prevention programmes would assure complete coverage of targeted children, coverage which prior to the war had reached only 2 regions or 20% of the eligible population. Now 100% of eligible children in government kindergarten and primary schools were to be targeted by 1999/2000.

Oral disease prevention strategies

The increase in funding for disease prevention programmes that targeted the most vulnerable population—the young child—represented a major shift in policy for the government. Evidence suggests that demand-side barriers are as important as supply-side factors in deterring patients from obtaining treatment [17]; here both demand- and supply-side barriers were addressed. Government spending on targeted oral disease prevention increased 3-fold from 1989/90 to 1994/95, in a period of declining revenues. The prevention strategy targeted all Kuwaiti kindergarten and primary school children in the public schools of Kuwait. The programmes included, among others, fluoride supplementation (lozenges), fluoride rinses and gels, plastic sealants, and stainless-steel crowns to reduce and prevent disease. If fluoridated salt (or water) became available to the public, the fluoride lozenges could be phased out. Distribution of fluoride toothpaste as a preventive agent was strengthened. Each programme in each district developed both area and national health promotion activities.

The oral health sector management team was able to procure these added resources in a period of declining financial resources by:

establishing national targets and goals;

presenting a complete, but simplified situation analysis to demonstrate to financial planners the urgency of instituting disease prevention programmes for the population most at risk in society—children;

comparing the results of the past decade with the results in more industrialized nations;

presenting budget documents that permitted the decision-makers to determine per capita costs for child care in these programmes, compared with the national health service, and providing the opportunity to select from competing alternatives.

Outcomes

Results of this aggressive strategic planning in children’s health have shown the following outcomes [18,19]:

Government spending on targeted oral disease prevention increased 3-fold in a period of declining revenues (1989/90 to 1994/95) (Table 1 ).

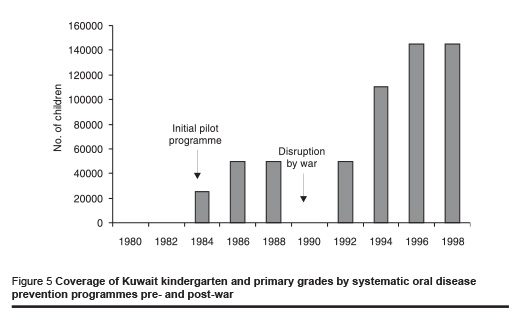

All Kuwaiti health regions now have a WHO type 3 systematic oral health programme for children (142 500 children enrolled, 95% of target) (Figure 5).

Caries prevalence has been stabilized or reduced in a minimum of 3/5 regions (Tables 2 and 3); caries intensity (dmft, DMFT indices for deciduous and permanent teeth) has been stabilized or reduced in the same regions (data not available in 2 regions) (Table 4).

Per child costs (programmes range from KD 13.7–18.0 per annum) are below the target of KD 25.0 per annum, and below Ministry of Health treatment costs of KD 26.5 per child (Table 5). While services have been scaled up, per unit treatment costs have been reduced.

Teams of oral health personnel have been trained at an international level of competence for specific tasks.

The distribution of dentists has changed, increasing the percentage working in children’s preventive programmes from 9.7% in 1982 to 28.0% in 1998.

The number of clinic units increased from 160 in October 1991 to 560 in 1998.

Dental school planning was completed for an integrated programme with the Faculty of Health Sciences, Kuwait University. The dental school graduated its first class in 2005.

The programmes for training dental hygienists and postgraduate general practitioners were re-established.

National protocols and manuals have been developed and implemented.

Intragovernmental and international cooperation has been strengthened.

A public–private sector partnership for oral health in Kuwait has been established.

Conclusions

Prime objectives for health promotion—access, development of personnel skills, cost-effectiveness, community participation, disease prevention and intersectoral collaboration—were achieved for oral health in the period 1992–2000. Demonstration of specific current and past disease data and of inadequate funding combined with the development of a national action-based strategic plan with key targets, led to substantial funding and staff increases in a period of declining revenues. In the post-war era, the health services management adopted an aggressive strategy that reoriented the focus of care for children from extraction and repair to primary prevention of diseases. A redistribution of dentists was achieved to reflect this philosophy and approach. While national programmes seldom have such an opportunity to reorient, Kuwait has demonstrated the success of strategic planning exercises to improve health.

Based on the experiences and results of this initiative, it would now seem appropriate for the Ministry of Health to review the impact of this planning and implementation process, and prepare new strategic plans for oral health services.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of Health, Kuwait funded this programme. The authors thank Mrs Maria Carmen for her patience in the preparation and typing of the manuscript.

References

- Behbehani EMH et al. After the war, oral health services in Kuwait. Proceedings of the International Conference on the Effects of the Iraqi Aggression on the State of Kuwait; 1994 April 2–6. Kuwait, Centre for the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, 1996:435– 47.

- Statistical review, 21st ed. Kuwait, State of Kuwait Ministry of Planning, Statistical and Information Sector, Central Statistics Office, 1998.

- Babeely K et al. Severity of nursing-bottle syndrome and feeding patterns in Kuwait. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 1989, 17(5):237– 9.

- Glass RL. National dental health survey of children. Kuwait, Kuwait Dental Services, Ministry of Public Health, 1982.

- Murtomaa H et al. Caries experience in a selected group of children in Kuwait. Acta odontologica Scandinavica, 1996, 53:389–91.

- Oral health survey of school children—Al Adan Kuwait. Kuwait, Dental Services, Ministry of Public Health, 1987.

- Vigild M et al. Dental caries and dental fluorosis among 4-, 6-, 12- and 15-year-old children in kindergartens and public schools in Kuwait. Community dental health, 1996, 13(1):47–50.

- Honkala E, Maidi D, Kolmakov S. Dental caries and stress among South African political refugees. Quintessence international, 1992, 23:579–83.

- Crall JJ. California children and oral health: trends and challenges. Journal of the California Dental Association, 2003, 31(2):125–8.

- Myburgh NG, Hobdell MH, Lalloo R. African countries propose a regional oral health strategy: The Dakar Report from 1998. Oral diseases, 2004, 10(3):129– 37.

- National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research. Strategic plan—2003– 2008. Journal of the American College of Dentists, 2003, 70(4):43–55.

- Hernandez SR. Formulating organizational strategy. In: Fottler MD, Hernandez SR, Charles L, eds. Essentials of human resources in health services organizations. Albany, New York, Delmar Publishers, 1998:20–7.

- Below PJ. The executive guide to strategic planning. San Francisco, Jossey–Bass Publishers, 1987.

- Morris RE. A national plan for oral health services Kuwait. Kuwait, Ministry of Health, 1992.

- Skougaard MR et al. The Danish dental health project in Kuwait. Tandlegebladet, 1991, 95:149–54.

- Gillespie GM. Proposal for an oral health programme in Mubarak Health Region, Kuwait. Kuwait, Report to Ministry of Health, 1992.

- Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health policy and planning, 2004, 19(2):69–79.

- Hawally school oral health programme. Kuwait, Report to Ministry of Health, Kuwait, 1998.

- Annual reports. Kuwait, Kuwait Ministry of Health, Division of Dental Services, 1994 to 1999.

- Kuwait national oral health survey. Oral health of 4, 6, 12 and 15 year old children in kindergarten and public schools in Kuwait. Kuwait, Ministry of Health, 1993.

- Annual reports. Kuwait, Ministry of Health, Finance Department, 1980 to 1995.

- Country profiles on oral health in Europe, 1991. Copenhagen, World Health Organization, 1992.

- Internal reports. Kuwait, Ministry of Health, Budget and Control Department, 1991 to 1998.

- Cohen LK, Gift HC, eds. Disease prevention and oral health promotion: socio-dental sciences in action. Copenhagen, Munksgaard Publishers, 1995.