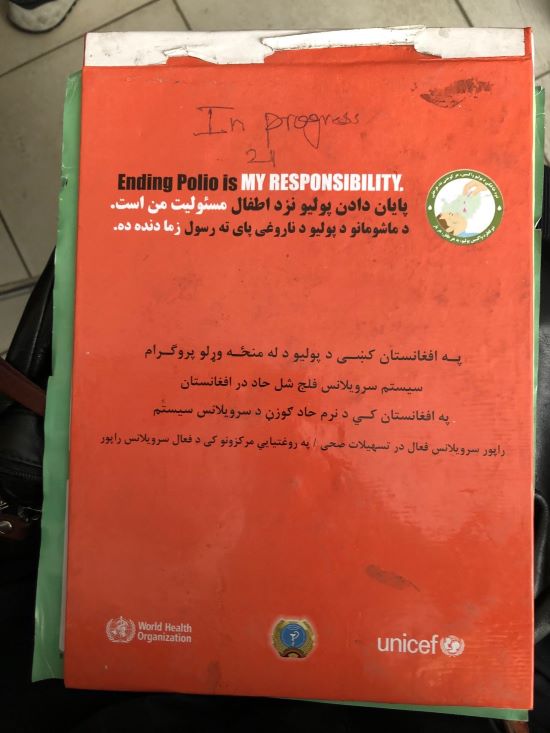

Details of all AFP cases are copiously recorded in Surveillance Registry books.

Details of all AFP cases are copiously recorded in Surveillance Registry books.

When a mother brought her young son to a clinic in Paghman, a town not far from the Afghan capital Kabul, Spogmai, a nurse on duty at the time, paid special attention.

“The mother was complaining that her son was weak and that the weakness had happened suddenly, so I examined his leg,” says Spogmai. “I saw that the limb was paralysed and immediately notified the clinic’s AFP focal point.”

AFP stands for acute flaccid paralysis. Surveillance for AFP - keeping an eye out for the signs of paralysis among children - is the cornerstone of polio eradication in one of the last countries where the virus is endemic. To eradicate polio, every last child must be vaccinated and, importantly, every last virus must be traced. A sign that the virus may be circulating in the community, every case of AFP is tested to confirm or rule out the presence of poliovirus.

Afghanistan is closer to interrupting polio transmission than ever before. In 2020, 56 children were paralysed by the virus; to date in 2022, the number has been reduced to 2. Vigilance is key and highly sensitive surveillance enables the polio programme to quickly detect the presence of polio and guides rapid targeted responses.

Like all staff at the clinic – doctors, nurses, cleaners, guards, administrative staff – Spogmai was trained to look out for signs of the virus.

“I had never seen a case of polio before, but I know how to watch out for it because I was trained to detect these things by the clinic’s medical officer. We have refresher training regularly to make sure we know.”

Orientation sessions for AFP surveillance are straightforward: they describe the signs of polio, what to look for and what to do next. Participants form part of a vast jigsaw of community-based surveillance across Afghanistan. Beyond the clinic’s doors is a network of more than 46 000 volunteers comprising religious leaders, hospital staff, private practitioners, staff at physical rehabilitation centres, mid-level health workers, community health workers, community volunteers, traditional healers, pharmacists, drug store staff and others working in health care, all looking out for signs of paralysis in children in their communities.

“Sudden onset paralysis in cases is more compatible with polio,” says WHO’s Dr Khushhal Khan Zaman, Medical Officer for Polio. “We don’t want any case of polio to be missed and spreading the virus. Every case of AFP is notified, investigated, followed up and documented.”

The local Provincial Polio Officer visits Spogmai’s clinic regularly to check on documentation and discuss cases with clinic staff. Details of all AFP cases are copiously recorded. Binders line the shelves of the surgery, holding details of cases going back more than a decade.

The scene in Paghman is repeated across the country in all of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, all part of the network of surveillance across the country. Spogmai’s clinic is a ‘CHC Plus’ clinic (a comprehensive health centre that provides additional services) and serves a large population in the district. Other health facilities such as basic health centres are smaller but regardless of their size, all staff are trained to look out for AFP cases and to report them to the designated focal point for further investigation.

Afghanistan’s AFP surveillance network was established in 1997 and the system is complemented by an environmental surveillance network consisting of 32 sites across the country. In June, the first review of the polio surveillance system in 6 years took place, with WHO hosting a 16-strong team of national and international experts who visited 76 districts across 25 provinces. The review determined the likelihood of undetected poliovirus transmission in Afghanistan to be low. Recommendations, including upscaling surveillance in the country’s south and south-east, are being implemented.

For Spogmai’s young patient, the next steps involved collecting 2 stool samples 24 hours apart which were sent to a WHO accredited polio laboratory for testing. The results were negative for polio and the young boy is living a healthy life with his family in the community, that same community that continues to ensure cases of AFP are spotted, recorded and tested.