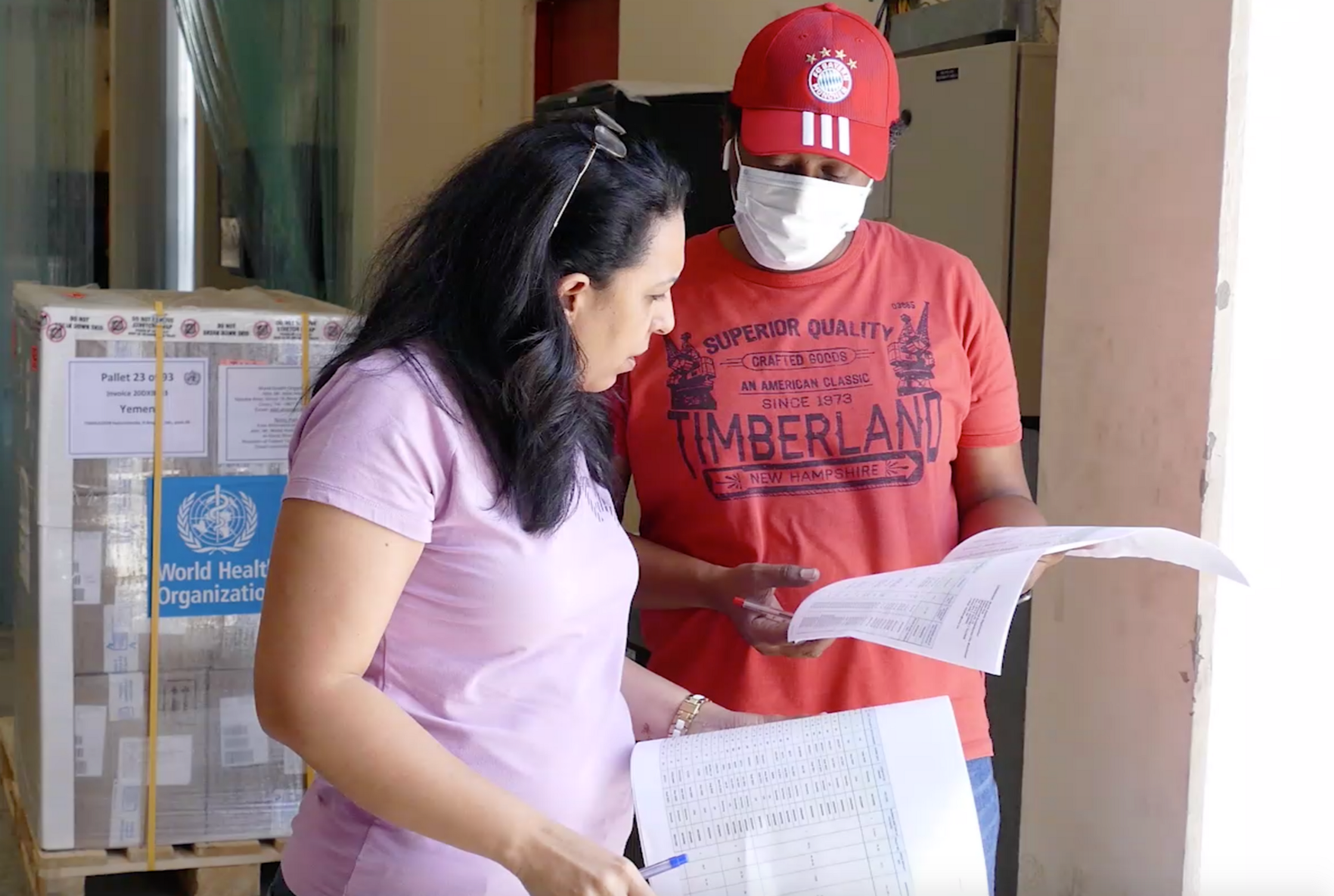

1 June 2020 – Nevien Attalla, a logistics expert for the World Health Organization, is used to coordinating massive shipments of medical supplies from WHO’s warehouse in Dubai to health facilities around the world. But in late May 2020, one particular shipment was a perfect storm: millions of dollars’ worth of lifesaving medicines, including COVID-19 laboratory tests and cancer medicine; delicate, sometimes dangerous supplies that required precise temperatures and ultra careful handling; airports shut down or running huge delays due to the pandemic; outside in Dubai, 40-degree heat. The destination: Yemen, a country wracked by war and complex to reach.

It was enough to affect anyone’s sleep, but Nevien wasn’t getting much anyways. She was busy fitting together puzzle pieces of the shipment ‒ packing the flammable items one way, waiting until the last minute to pack temperature-sensitive COVID-19 tests – and recalculating it all when a new surprise or delay hit.

During a whirlwind week, Nevien shared her experiences via voice and text messages.

Day one

Sorting through pages of shipping documents and long Excel spreadsheets, Nevien, a pharmacist, reviews the supplies. “This is the most complicated and expensive shipment so far,” she says. “It has all the complexities.” There are cancer treatment medicines, urine analysis kits, antibiotics, and reagents for laboratory tests that help diagnose COVID-19 and other diseases. The laboratory testing items must be kept below freezing.

The personal protective equipment (PPE) is easier from a shipping standpoint, but there’s a lot of it: masks, gloves, goggles. Then there’s the “DG” ‒ dangerous goods ‒ “laboratory stains and reagents,” she explains. “Mainly formaldehyde, ethanol gram stain kit ‒ the stain kit they are using in the laboratory to check the type of bacteria or the virus. It’s DG because it’s corrosive and easily inflammable.” Some of them must be kept in the dark.

Nevien has to figure out how to get all the supplies trucked to Dubai’s airport and then flown to Yemen, undamaged. And in some crucial cases, cold.

Day two

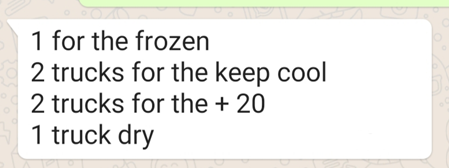

Signs are that the airplane might arrive tomorrow, so Nevien starts getting ready for loading day. She’s ordering trucks that will each be set at the requested temperature: -20 °C for items that must be frozen; 2–8 °C; 20–30 °C; and “dry” for items that won’t be damaged by high temperatures. There will be 6 trucks in total bringing the supplies from the WHO warehouse to the Dubai airport:

In particular, if the COVID-19 testing materials don’t stay cold, they might not be usable to test patient samples in Yemen. The enzyme that creates a chemical reaction needs to be below freezing or it will be inactivated.

If there’s a delay and the dry ice evaporates, the supplies get too warm and laboratories in Yemen won’t be able to confirm who has COVID-19 and who doesn’t.

Keeping this “cold chain” going, especially in hot countries, is an ongoing challenge for WHO’s medical logistics professionals.

Nevien keeps making calls. Meanwhile, a special company packs and labels the dangerous goods.

The day’s work is based on a best-case scenario ‒ that the plane will come as planned. The flight is a charter generously provided by another group, but it means WHO doesn’t have control over some of the timing.

Day three

In the morning, loading begins. Some of the shipment is made up of emergency kits, which contain things like antibiotics that don’t require as much special handling.

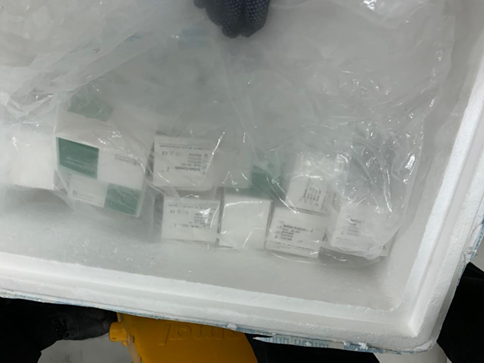

Meanwhile, Nevien and her colleague carefully open the warehouse freezers holding the laboratory supplies that help diagnose COVID-19 and other diseases. Moving quickly, they pack the items into Styrofoam containers and pour in dry ice.

They tape a special USB drive to the side of the box; it logs temperature, so when the box is opened in Yemen, health workers can plug the drive into their computers to see if there were temperature fluctuations that would affect the COVID-19 supplies.

In the middle of the dry ice packing, with the other loading already finished, Nevien gets a message from the group in charge of the plane. There’s an issue and the flight will be delayed for 2 days.

Everything has to go back into the warehouse.

“It’s so disappointing,” says Nevien. But her sigh is short. She’s already thinking ahead.

She takes another breath. “OK.”

Day four

Nevien works on another charter, also sending medical supplies to Yemen, but to another region there. “Plus other shipments are going and coming,” she says. An upcoming holiday will complicate things further. With many airports closed to passengers and cargo because of the pandemic, getting special permission for humanitarian supplies takes extra effort.

“What’s happening now, I’ve never seen it before,” she’d said earlier in the week. “With COVID-19, every day is a work day. Everything now is challenging.

“From January to December 2019, we did 92 shipments. It’s mid-May 2020, and we’ve already sent 180 shipments to 102 countries across every WHO region ‒ from the Americas to the Western Pacific.”

“In 4 months, we worked more than all of last year.”

Day five

“We’re on standby for the Yemen shipment,” says Nevien’s morning text. “Once we received confirmation on the land permit, I will ask the trucks and the ice to come again.” While she waits, she works on permissions for 10 other shipments related to COVID-19, including a flight sending PPE to Islamic Republic of Iran.

By noon, things are in motion for the Yemen flight.

But there’s an issue. “For transportation of the 2‒8 °C supplies, the truck came at a temperature of 14 °C. We waited for it to reach the range which we want, but unfortunately after 2 hours it wasn’t at the correct temperature,” she says. She asks the transport company to send another truck.

Meanwhile, “The minus” ‒ the truck carrying the frozen items ‒ “is already packed,” she says in a voice message. The beeping sound of trucks backing up is loud in the background.

By 17:30 Dubai time, the trucks are on the road.

Late that evening comes another voice message. “It’s postponed again, after the trucks were almost at the airport,” says Nevien. “We reached Sharjah airport and asked them to keep the trucks in their warehouses.

The worry now is how to keep the laboratory supplies , including the COVID-19 items, frozen. “The dry ice can stay as ice for 48 hours. If the plane comes tomorrow instead of today, and it departs tomorrow morning, there’s no need to do any repacking,” she says.

“But if it’s after tomorrow … after some hours it will completely evaporate, even if it’s inside the freezer,” she continues. “So we need to do a repacking if the cargo will not depart tomorrow.”

Day six

So: the plane. Where is it?

The earlier delay was more paperwork-related. This one’s due to weather ‒ thunderstorms and wind at high altitudes. All day, Nevien and the WHO warehouse team wait, plan, readjust.

Around 19:00, they get word that the flight should land in a few hours. The COVID-19 curfew for Dubai is 20:00. The WHO team sends a staff member to a supplier for 30 kilograms of dry ice. The WHO team spends the better part of 24 hours communicating with one another, local suppliers, freight forwarders, and airport staff.

The clock is ticking. There’s a COVID-19 curfew, too.

They get special permission to hand over the dry ice and finalize the repackaging just in time.

At 21:00, the long-awaited airplane lands.

Day seven

In the dark of night, the medical supplies are loaded onto the plane. The airport allows one of their staffers to take the dry ice and repack the items that need it, reports Nevien.

Sharjah Aviation Services often helps WHO with emergency shipments like this one; Nevien is grateful that the United Arab Emirates is so attuned to the health crisis and WHO’s role. They’re always helpful when WHO approaches them, she says. But with the COVID-19 crisis, “They’re not waiting for us to come to them. They’re coming to us saying, ‘How can we help?’”

Finally comes the text message that’s taken a week “The flight took off from Dubai!”

And then at 13:30 Yemen time:

Health workers in Yemen won’t have to wait much longer for the COVID-19 tests, cancer medicines, and protective gear they are running short of.

“When the plane takes off, I feel like all our hard work and effort has value,” says Nevien.

Week two

Everything begins all over. The next flight to another part of Yemen is complex too. Plus there’s Syria. And Myanmar. And Sudan.

WHO’s Dubai hub is on track to deliver 250 shipments within the first 6 months of 2020. It’s already delivered to 5 times the number of countries that it usually ships to. As of May 2020, it has sent over 16 million US dollars’ worth of medical supplies, representing more than 1200 metric tons, 4000 pallets, or as a WHO team member says, 200 African elephants’ worth of medical supplies to be used across Yemen.

The 6 other people on the WHO team are working the same long hours at the Dubai warehouse, sometimes sleeping there, getting the supplies out during the crisis. Teams on the receiving end are doing the same ‒ distributing lifesaving supplies to the far corners of the world.

“Alone I can’t do it. It really is teamwork,” says Nevien. “It is a stressful period, but we are glad to be at the core of WHO’s global response to the pandemic.”