Select your language

Faces of health

Across the continents and cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean Region, remarkable individuals are transforming their communities with the support of WHO, one act of care at a time. Whether delivering life-saving vaccines or providing mental health support, these Faces of Health embody resilience, compassion and unwavering dedication. Their stories reflect a shared mission that transcends borders: achieving Health for All.

Farahnaz Rahmanyar

Hope and healing in Herat

For nearly 8 years, community health worker Farahnaz Rahmanyar has been a reassuring presence, commanding the trust and respect of the families she serves.

In the suburbs of Herat Province, where dusty roads divide modest homes, Farahnaz walks with purpose. House to house, day after day, she brings hope and healing, educating mothers and helping to ensure that their children thrive.

In the suburbs of Herat Province, where dusty roads divide modest homes, Farahnaz walks with purpose. House to house, day after day, she brings hope and healing, educating mothers and helping to ensure that their children thrive.

“I’m grateful for the trust people place in me,” says Farahnaz. ”And with that trust comes responsibility. Through our volunteer work, we are helping our communities take meaningful steps towards a healthier life.”

Farahnaz has attended WHO trainings on the management of acute respiratory infections, diarrhoea, malaria and other common communicable and noncommunicable diseases, gaining knowledge that she now shares with local communities.

“Thanks to the programmes organized by WHO, we learned about diseases that are common in our locality and are now able to provide better health services to our people, especially pregnant mothers and children under 5,” says Farahnaz.

As a result of her enthusiasm and hard work more pregnant women attend routine checkups, more children under 5 receive lifesaving vaccinations and mothers are gaining the knowledge they need to protect their children from malnutrition. Awareness has risen. Hundreds of people have received the right health care.

“Our efforts as volunteers staffing local health posts have contributed to a meaningful reduction in child and maternal mortality. Through disseminating health information and raising awareness we’ve been able to significantly lower maternal deaths in our communities.”

“Our efforts as volunteers staffing local health posts have contributed to a meaningful reduction in child and maternal mortality. Through disseminating health information and raising awareness we’ve been able to significantly lower maternal deaths in our communities.”

Each health post is staffed by a male and female community health worker who serve between 100 and 150 households, providing preventive and basic curative health care services, including health education, vaccination and treatment for common illnesses alongside maternal health care, family planning services and, when necessary, referrals to higher-level facilities.

Building trust. Talking health. Spreading hope. It’s what Farahnaz, and the many community health workers like her, do. She is a lifeline for the families she serves. A daughter of the community. One of the many faces of health.

A story of hope and healing in Herat, Afghanistan

From the heart of a far suburb in Herat, Afghanistan 🇦🇫, Farahnaz Rahmanyar walks every day from one doorstep to another to deliver health care, hope and education to hundreds of people. For eight years, she has devoted her life to one dream: a healthier community.

Her dedication and compassion have earned her trust and respect among her community. Thanks to Farahnaz:

hundreds of pregnant women are attending routine checkups

more children under five are receiving life-saving vaccinations

mothers have learned to protect their children from malnutrition

Amjad Al-Mahari

Courage and innovation

Bahrain has taken a historic step in the field of medical innovation with the successful treatment of Mr Amjad Al-Mahari, the first patient outside the United States to undergo CRISPR gene-editing therapy for sickle cell disease.

Sickle cell disease has long been a public health concern in Bahrain, requiring continuous efforts in both treatment and prevention. The introduction of CRISPR technology in the Kingdom reflects how investment in research, partnerships and innovation can bring tangible results for patients.

Mr Al-Mahari’s case is not only a personal success; it is a symbol of Bahrain’s commitment to advancing modern medicine. His recovery marks a milestone for the Kingdom.

The treatment process was long and complex. It required careful preparation, and great resilience on the part of Mr Al-Mahari who undertook the procedure fully aware of the challenges and potential risks involved. His successful recovery is due in no small part to Mr Al-Mahari’s determination and courage. It is the result not only of medical advances but of the patient’s strength and willingness to embrace this groundbreaking treatment.

The treatment process was long and complex. It required careful preparation, and great resilience on the part of Mr Al-Mahari who undertook the procedure fully aware of the challenges and potential risks involved. His successful recovery is due in no small part to Mr Al-Mahari’s determination and courage. It is the result not only of medical advances but of the patient’s strength and willingness to embrace this groundbreaking treatment.

The World Health Organization (WHO) works closely with the Ministry of Health and other partners to strengthen health systems and ensure that innovative treatments can be integrated into care. This aligns with WHO Bahrain’s focus on key health priorities, including the management of noncommunicable diseases, preparedness for health emergencies and the promotion of equitable access to advanced care.

Both the WHO Director-General and the WHO Regional Director for the Eastern Mediterranean highlighted Bahrain’s health innovations during their visits to the Kingdom. The visits underscored Bahrain’s leadership in adopting advanced health solutions, and it is notable that both met with Mr Al-Mahari.

While the journey of Amjad Al-Mahari – Bahrain’s nominee for the WHO Faces for Health campaign – exemplifies personal courage, it also stands as a testament to the Kingdom’s vision for the future of health care and the role of WHO Bahrain in supporting this vision, underlining how scientific breakthroughs can directly improve lives and inspire progress across the Region.

Arafo Daher Ainan

Building trust step by step

At dawn in Ali Sabieh, nurse anaesthetist Arafo Daher Ainan checks the cold box, confirms the day’s route and sets out with the outreach team. It is a familiar routine. For more than 11 years Arafo’s work has involved travelling long distances, in environments where health service delivery depends on trust.

At dawn in Ali Sabieh, nurse anaesthetist Arafo Daher Ainan checks the cold box, confirms the day’s route and sets out with the outreach team. It is a familiar routine. For more than 11 years Arafo’s work has involved travelling long distances, in environments where health service delivery depends on trust.

During Djibouti’s polio campaign, Arafo supported supervision in hard-to-reach peripheral areas, safeguarding the cold chain and helping teams prepare for the long trek on foot between scattered households. While the technical steps – temperatures recorded, vials counted, registers signed – are essential, the turning point often involves quiet conversations on shaded doorsteps.

Arafo is a good listener. She wants to know what worries her patients most, what they have heard. She answers questions clearly, respectfully, addressing hesitancy without judgment.

“Trust is built step by step, she says. When a mother feels heard, she will choose protection for her child.”

The Ministry of Health and WHO support Arafo’s and her colleagues’ work with microplanning, training, supportive supervision and evidence-based materials adapted to the local context. These resources help teams organize routes, maintain cold chain integrity and deliver messages that make sense to the families they meet.

The Ministry of Health and WHO support Arafo’s and her colleagues’ work with microplanning, training, supportive supervision and evidence-based materials adapted to the local context. These resources help teams organize routes, maintain cold chain integrity and deliver messages that make sense to the families they meet.

One afternoon, after a long discussion, a mother who had been unsure finally nods and holds her child close while Arafo prepares the oral drops. The scene lasted seconds. The effect will last years.

Arafo’s story reveals the practical side of WHO collaboration – logistics that work, messages that resonate and teams that are supported as they strive to overcome every hurdle in their quest to ensure no child is left behind. It also reflects the values – empathy, clarity and perseverance – that inform her work.

“Even if we walk for kilometres, she says, every child counts.”

‘Every child counts”. Three simple words with enormous impact. What they mean is that children are protected, and that families and communities across Djibouti are moving closer to a future free of polio.

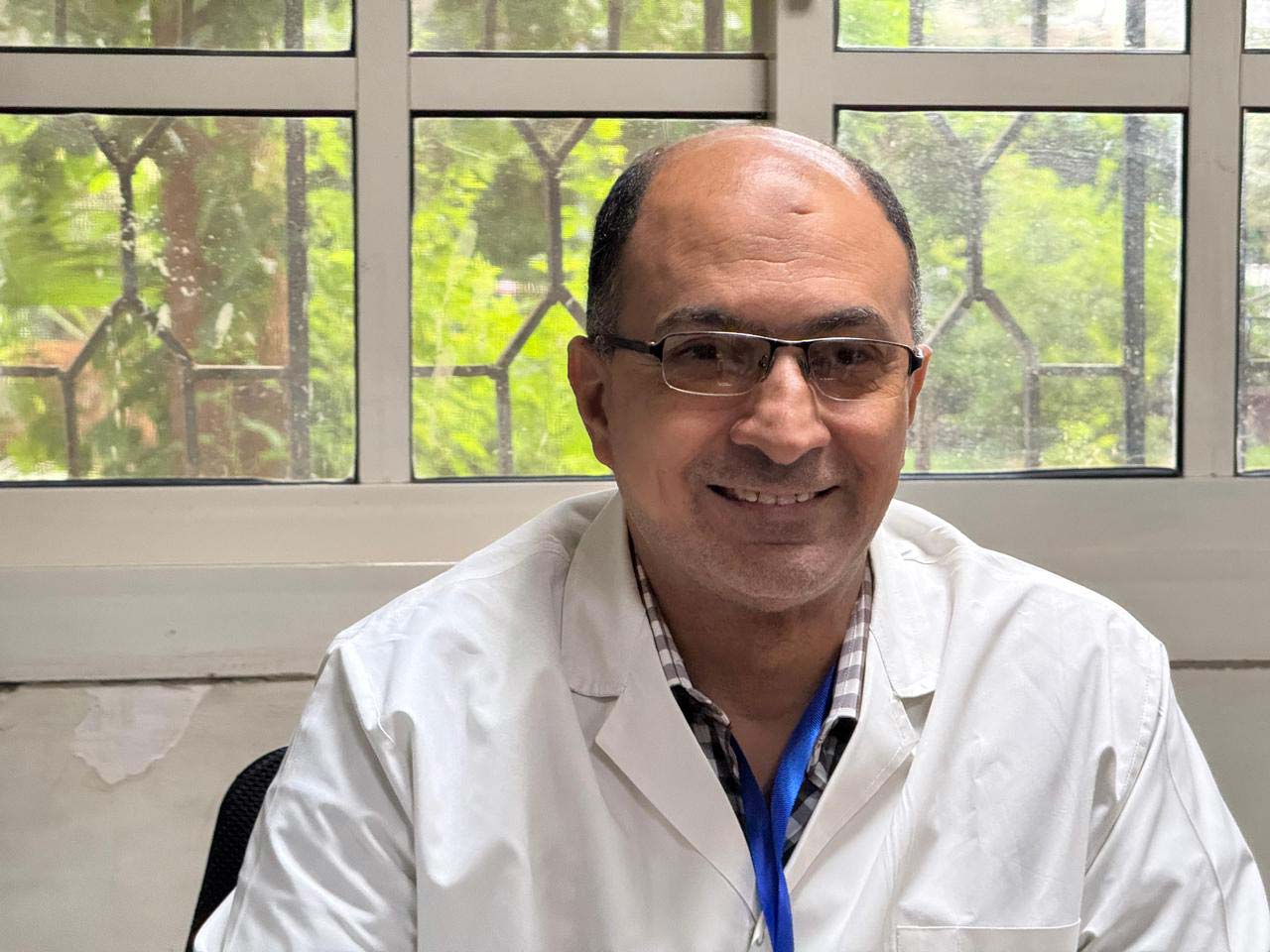

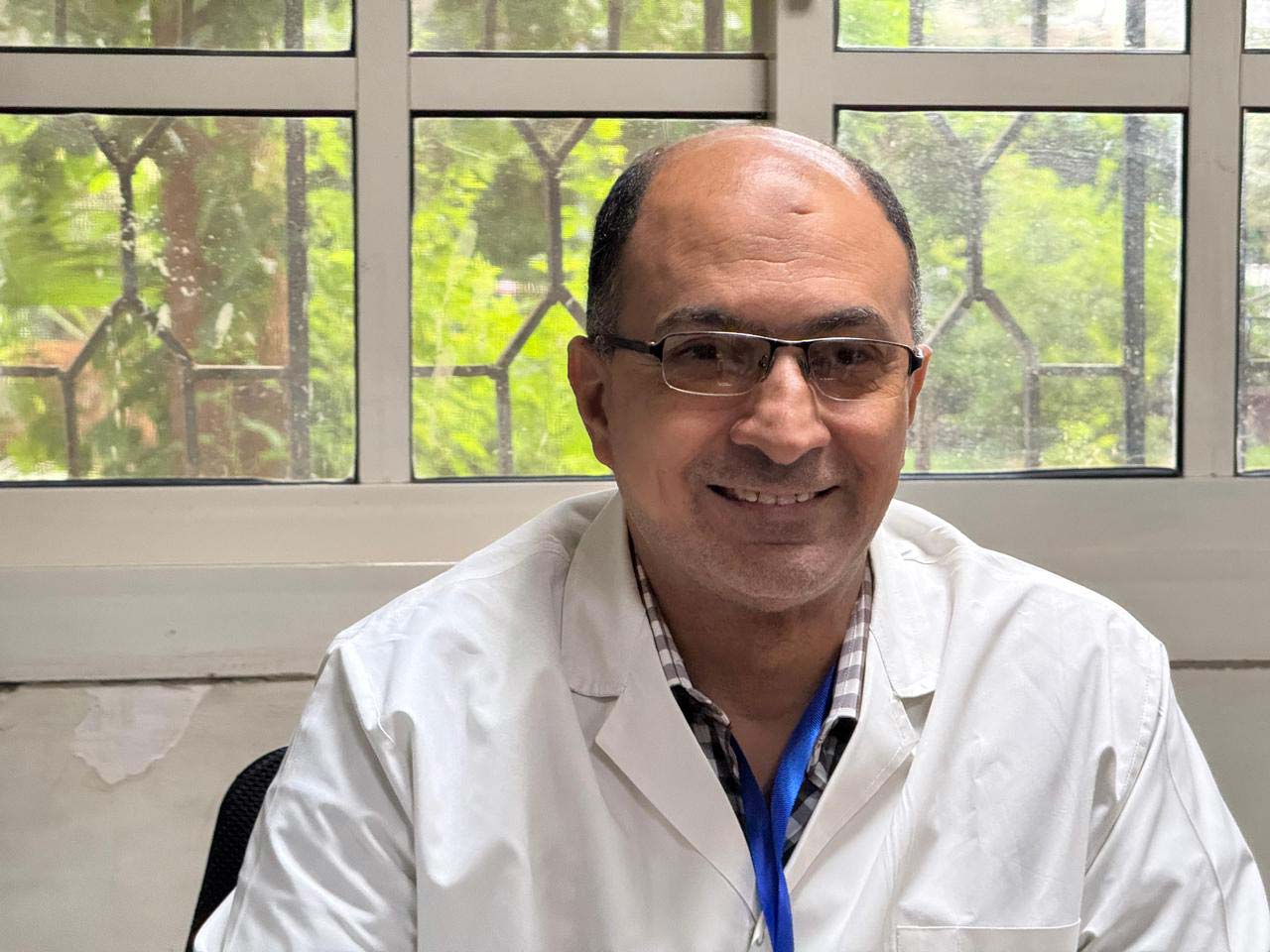

Dr Essam Hassan

Bringing relief to renal failure patients

Nephrologist Dr Essam Hassan is deputy manager at Al-Agouza Hospital in Giza. Each morning, he arrives at his office at 8 am, ahead of the dozens of patients who come seeking consultations every day.

Many of his patients are Sudanese refugees, others are Egyptian. He carefully reviews the laboratory results of each patient, adjusts their treatment plans if changes are needed and, more often than not, shares a light joke to ease the tension of the situation.

Many of his patients are Sudanese refugees, others are Egyptian. He carefully reviews the laboratory results of each patient, adjusts their treatment plans if changes are needed and, more often than not, shares a light joke to ease the tension of the situation.

Many of the Sudanese patients who visit Dr Essam cannot afford the expensive medications that are often needed to treat renal failure which is why a joint project between KSrelief and WHO Egypt, under the leadership of the Ministry of Health and Population, is so important.

The initiative provides free dialysis sessions and post-transplant medications for Sudanese patients, aiming to eventually reach 1000 people. So far, more than 150 patients are enrolled for dialysis and 250 are receiving medications, of whom 110 Sudanese patients are supported at Al-Agouza Hospital.

For Dr Essam, the impact of the project has become deeply personal.

“It makes a real difference to me to know that I am helping relieve the suffering of patients, and it brings me happiness to follow up with people who would otherwise not have the chance to see a nephrologist,” he says.

Hawraa Seifeddine

A social worker’s mission

In 2020, Hawraa Seifeddine graduated from the Lebanese University with a degree in health social work. Since then, her professional life has been shaped by her engagement with humanitarian and psychosocial support initiatives.

In 2020, Hawraa Seifeddine graduated from the Lebanese University with a degree in health social work. Since then, her professional life has been shaped by her engagement with humanitarian and psychosocial support initiatives.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Hawraa supported children and parents who were either quarantined or infected. Through group activities and therapeutic play she helped children cope with emotional stress and provided sessions on anger management, fear, stigma and grief counseling.

Hawraa has worked with the World Health Organization (WHO) in mental health and elderly care centres. Most recently, she has been supporting the lifesaving and limb-saving hospitalization programme. Her responsibilities include managing a medical hotline, helping to ensure each case is evaluated against programme criteria and follow up support is delivered.

The position brings her into close contact with people in urgent need of medical care. One recent case involved a 2-year-old girl who required urgent hospitalization. The child's family could not afford a medical consultation but thanks to Hawraa’s intervention the girl was examined by a UNICEF-affiliated doctor and subsequent treatment costs were covered by an NGO.

As well as direct case management, Hawraa supports families experiencing bereavement or facing health crises, providing guidance on how to access essential services, conducting well-being checks on parents and caregivers and working on injury prevention, particularly in homes where children or elderly individuals are at risk of falls and fractures.

Helping to ensure patients are treated with dignity is central to Hawraa’s work. She has contributed to simplifying procedures based on user feedback, minimizing the amount of documentation and paperwork required to access services.

Raising public awareness about the programme’s services is key to outreach efforts. Hawraa collaborates with social workers in schools, hospitals, NGOs and municipalities, increasing the programme’s visibility and expanding its reach across Lebanon.

During the early stages of the recent conflict, Hawraa helped maintain the continuity of services by staffing a round the clock hotline, coordinating support for hospitals and connecting patients with care providers. On top of everything else, she also volunteers with the Syndicate of Social Workers, regularly taking part in school visits and closely monitoring the needs of displaced families.

Salwa Al-Zaben

Building trust in East Amman

Health is a human right, not a privilege, says Salwa Al-Zaben. Born and raised in the community of Umm Al-Amad in East Amman, Salwa grew up surrounded by family and neighbours, people whose lives were deeply intertwined with her own.

Health is a human right, not a privilege, says Salwa Al-Zaben. Born and raised in the community of Umm Al-Amad in East Amman, Salwa grew up surrounded by family and neighbours, people whose lives were deeply intertwined with her own.

Health is a human right, not a privilege, says Salwa Al-Zaben. Born and raised in the community of Umm Al-Amad in East Amman, Salwa grew up surrounded by family and neighbours, people whose lives were deeply intertwined with her own. It is this bond with her community that has shaped Salwa’s working life, driving her ambition to ensure that every child receives lifesaving vaccines, regardless of background or circumstance.

Salwa began with midwifery and nursing. She then went on to complete a Master’s in disaster and crisis management and specialized training in field epidemiology. Since joining the Ministry of Health in 2016, she has worked across maternal and child health, vaccination programmes and emergency response. In 2019, she took on a new challenge, leading the mobile vaccination team in East Amman.

The area she covers spans four large districts, Al-Jeeza, Al-Muwaqqar, Al-Qweismeh and Sahab, home to diverse and often marginalized populations including Syrian refugees, Pakistani labourers, Bedouins, Kurds and Turkmen. Many of these communities live far from health centres, in temporary housing or agricultural camps.

The area she covers spans four large districts, Al-Jeeza, Al-Muwaqqar, Al-Qweismeh and Sahab, home to diverse and often marginalized populations including Syrian refugees, Pakistani labourers, Bedouins, Kurds and Turkmen. Many of these communities live far from health centres, in temporary housing or agricultural camps.

It is difficult for many families to access vaccines. Health centres are distant, the cost of transport high. Salwa and her team help bridge this gap. With vaccines packed in portable coolers, syringes and health education materials, they travel to remote villages and farms, holding 8 outreach sessions each month.

The key to Salwa’s success lies less in logistics than in trust. “Trust is everything,” she says. “Without it, people won’t open their doors, won’t listen and won’t let you vaccinate their children.”

Attending weddings and funerals, listening to people’s concerns and showing up exactly when she promises, Salwa has spent years building trust. Over time, community leaders, imams and youth influencers became her allies, helping gather families and spread the news. Salwa is coming today. Bring your children!

Communities once hesitant about vaccines now call her directly for advice.

For Salwa, this is more than a job. It is a calling rooted in love for her people and the belief that every child deserves protection and hope for a healthy future.

“When I vaccinate one child I am protecting a family,” says Salwa. “And when I protect families, I am building a more resilient community.”

Salwa Al-Zaban builds trust in East Amman

Meet Salwa Al-Zaban, the daughter of Umm Al-Amad community in East Amman who aims to make her community more resilient with vaccination efforts.

Salwa and her team travelled to remote communities to give children access to vaccines at the comfort of their homes, making sure no child is left behind. Some children may miss a dose because it’s challenging for their parents to reach distant health centres with expensive transport.

Sadiq Mohamed Baqir

Healing minds, healing communities

Psychiatrist Sadiq Mohamed Baqir is the Technical Director at Al-Qanah Centre for Social Rehabilitation. His interest in psychiatry began with a simple yet powerful observation – mental health is not given the attention it deserves.

Psychiatrist Sadiq Mohamed Baqir is the Technical Director at Al-Qanah Centre for Social Rehabilitation. His interest in psychiatry began with a simple yet powerful observation – mental health is not given the attention it deserves.

“During my early studies, I saw how individuals struggling with psychological disorders were often neglected or exploited by unqualified practitioners. This reality shaped my vocation. I decided to dedicate my career to psychiatry, offering care and professional support to those who need it most”, he says.

The stigma surrounding mental health is pervasive. Prejudices – from relatives, the public, even colleagues – create barriers between patients and physicians, compounding the suffering of people already in pain. In response, Mohamed focused on raising awareness, spreading knowledge and patiently building trust.

“Over the years, attitudes began to shift. Friends, relatives and even fellow doctors started approaching me for guidance – a sign that perceptions can indeed change.”

“I often hear the painful words: ‘Doctor, I wish I had any other illness than this’. Such expressions reflect both the depth of suffering and the weight of society’s judgment. Yet nothing compares to the joy of seeing recovery, watching patients gradually heal and knowing their families are also finding relief and hope.”

“Psychiatry,” says Mohamed, “has transformed not only my career but my character. It has made me more empathetic and patient. True healing comes from both medical knowledge and compassion.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) is working to strengthen mental health services in Iraq. Together with the Ministry of Health, WHO organized a training workshop on treatment protocol for addiction and psychosocial rehabilitation, bringing together doctors, pharmacists, nurses and mental health researchers.

Mohamed helped prepare and present the protocol, engaging in interactive sessions with participants.

“ These discussions helped empower professionals, equipping them with tools to improve mental health care across Iraq” , he says.

“ My message is simple but urgent. Mental health is just as important as physical health. Seeking help is not weakness, it is courage. By advancing mental health we not only heal individuals. We are building a more compassionate, resilient society.”

Bita Mesgarpour

How collaboration helped a nation through crisis

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr Bita Mesgarpour and her team at the Ministry of Health and Medical Education’s National Institute for Medical Research Development faced a perfect storm. They had to develop and evaluate vaccines under emergency conditions.

Working with WHO proved to be a lifeline. Dr Mesgarpour and her team were able to contain the crisis by collaborating with WHO to share data and expertise. WHO acted as a bridge, allowing the Ministry of Health to join multicentre studies and global health initiatives, opening the door to partnerships with leading research institutions and regulatory bodies.

Working with WHO proved to be a lifeline. Dr Mesgarpour and her team were able to contain the crisis by collaborating with WHO to share data and expertise. WHO acted as a bridge, allowing the Ministry of Health to join multicentre studies and global health initiatives, opening the door to partnerships with leading research institutions and regulatory bodies.

By participating in WHO-aligned studies "Iran was able to share its scientific capabilities and learn from others," creating a sense of global solidarity and resilience, says Dr Mesgarpour.

The stakes were high. Every choice had to be based on solid evidence. Partners were able to provide technical expertise in trial design and platforms for knowledge exchange. The team leveraged WHO-standard Request for Proposals (RFPs) to launch rigorous vaccine comparison studies. Reliable, standardized data allowed the Ministry of Health to compare vaccine efficacy and safety across populations. Decisions could be made based on the best available evidence.

"When data and analysis are reliable,” says Dr Mesgarpour, “then we are on the right track."

In the darkest moments, truth is the most powerful tool. By ensuring that every health decision was grounded in solid scientific evidence, Dr Mesgarpour and her team became a lifeline for millions of Iranians. They were able to move forward with confidence and make those final, critical decisions.

Guided by evidence, united by a common purpose, this is what lies at the heart of global health. It is a story of trust, collaboration and the quiet heroism of health care workers – from research teams that develop treatments to the people who administer them – and their shared determination that nothing be allowed to get in the way of saving peoples’ lives.

Mouna Laaroussi

Living with bipolar disorder

Mouna, who has lived through bipolar disorder, emerged from the experience stronger, wiser and ready to support others.

Mouna, who has lived through bipolar disorder, emerged from the experience stronger, wiser and ready to support others.

“I used to see things differently, she says. Not like they really were.”

It was her mother who first noticed something might be wrong. She took Mouna to see a psychiatrist. Initially, Mouna refused treatment. But then her life began to spin out of control.

Recognizing this – “I felt my soul was eclipsed or shut off,” says Mouna – she finally accepted treatment, only to find herself in a vicious cycle of studying and taking medication.

She was told by the psychiatrist that she had “mood swings”. “He didn’t want to tell me the name of my condition, which is bipolar disorder,” says Mouna.

What followed was a period of struggle. Mouna would see her doctor sporadically. She dropped out of college in the second year. She would change jobs, alternating periods of working with study.

In 2010, Mouna received a marriage proposal. She accepted, but after marrying found it difficult to strike a life-work balance. Juggling the responsibilities of running a household and looking after her husband, Mouna felt she was losing control and quit her job.

Deciding she wanted a child, Mouna spoke to her psychiatrist who discouraged her from becoming a mother. The advice compounded Mouna’s feelings of depression.

Seeing her daughter’s distress, Mouna’s mother took her to see a different psychiatrist who explained Mouna’s diagnosis and told her it was perfectly OK to conceive and become a mother. Mouna asked for further consultations and follow up and enrolled in a series of workshops. Her journey towards healing had begun.

“I joined expressive art therapy and self-esteem and self-confidence enhancement workshops and gradually started to get my life back on track.”

Noting Mouna’s improvement, her psychiatrist suggested she become involved with the centre’s peer support group.

“This involved assisting others as someone who has experienced bipolar disorder,” says Mouna. “I’m now helping others, benefitting myself and those in need.”

In Morocco, mental health is a national priority. With support from WHO, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection developed the 2023–2030 mental health action plan and created a mental health information system for improved service delivery. Despite continuing challenges such as workforce shortages, these efforts mark an important step towards improving the mental health system.

Bipolar disorder: A journey from “distress to being a beacon of hope”

Mouna, from Morocco, shares her journey of recovery from bipolar disorder– from being unable to function well to coping with her illness using various strategies she inspires us with how she turned her distress of into “a blessing”. Today, she is able to draw on her lived experience to help others as a peer supporter.

Mental health problems are among the top 10 leading causes of disease burden worldwide and are the single largest contributor to years lived with disability.

Dr Zeyana Al Habsi

Breaking the stigma around HIV

As Head of the AIDS, Sexually Transmitted Infections and Hepatitis Section at Oman’s Ministry of Health, many of the individuals Dr Zeyana Al Habsi supports face psychological and social challenges that go beyond their diagnosis.

As Head of the AIDS, Sexually Transmitted Infections and Hepatitis Section at Oman’s Ministry of Health, many of the individuals Dr Zeyana Al Habsi supports face psychological and social challenges that go beyond their diagnosis.

“My mission,” she says, “is to offer hope, to help them integrate fully into society and remind them they are not alone.”

"As a representative of the AIDS programme, I am deeply committed to supporting people living with HIV, not only medically but also emotionally and socially. At Al Nahdha Hospital, I witness firsthand stories that reflect both struggle and resilience, stories that deserve to be met with compassion, dignity and hope.”

Beyond the clinic, Dr Zeyana is passionate about raising awareness and breaking the stigma surrounding HIV. She actively engages with communities through women's societies, NGOs and media platforms to share messages of acceptance and empowerment.

“My role is not just to support individuals but to inspire communities to stand beside them, to fight discrimination and to embrace every person’s right to live a fulfilling and meaningful life."

Dr Zeyana is equally committed to raising awareness about the importance of early HIV testing, which is not only critical for the health and well-being of individuals but plays a key role in protecting others, including spouses, children and the wider community, by preventing further transmission.

“Through sharing messages of hope, promoting early testing and actively challenging stigma, I aim to empower people to take control of their health and live positively. My mission is to help build a society that is more inclusive, compassionate and supportive for everyone, especially those living with HIV."

Dr Zeyana is grateful to the World Health Organization for providing evidence-based guidelines and comprehensive training to support HIV/AIDS and syphilis programmes across Oman.

WHO’s strategic frameworks, she says, help support her advocacy to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis, reduce stigma and promote early testing nationwide.

By focusing on capacity-building to deliver holistic care, these trainings help ensure people living with HIV and their families receive vital medical, emotional and social support. In alignment with WHO’s global initiatives, Dr Zeyana contributes daily to a unified effort to foster inclusive, compassionate communities across Oman.

Ihab Abu Hatab

Supporting health care under fire

Ihab Abu Hatab is a Supply and Logistics Officer with WHO oPt. A husband and father of 5, he lives and works in Gaza. Each morning Ihab wakes with a single purpose – to serve his people, even as the world around them crumbles.

Ihab Abu Hatab is a Supply and Logistics Officer with WHO oPt. A husband and father of 5, he lives and works in Gaza. Each morning Ihab wakes with a single purpose – to serve his people, even as the world around them crumbles.

“Being a humanitarian during 2 years of conflict has been a relentless test of strength and faith,” says Ihab. “It’s not just about delivering aid, it’s about doing so with bombs and violence and uncertainty everywhere. The obstacles are endless, but my team never stops. People depend on us. That responsibility fuels me every single day.”

Ihab and his team have endured unimaginable hardship. One of the most lifechanging moments came during the military attack on the WHO staff guesthouse (21 July 2025) in which his family had taken refuge after their home was destroyed in March 2024.

“That day, I felt our lives hanging by a thread. The fear in my children’s eyes, the sound of attacks shaking the walls, the destruction of everything we owned... But instead of breaking me, it strengthened my resolve. I realized I couldn’t give up. I had to keep strong, for my family and for my people.”

Despite the hardships, Ihab’s work has brought moments of pride. One of the proudest came in May 2024, at the start of the Rafah incursion, when he and his team evacuated over 2000 pallets of critical medical supplies from warehouses in just 3 days, moving them to hospitals and another WHO warehouse.

Despite the hardships, Ihab’s work has brought moments of pride. One of the proudest came in May 2024, at the start of the Rafah incursion, when he and his team evacuated over 2000 pallets of critical medical supplies from warehouses in just 3 days, moving them to hospitals and another WHO warehouse.

“The supplies were a lifeline for countless patients and health facilities,” says Ihab. “The pressure was immense but we succeeded, under the direst conditions. That experience was a powerful reminder of why our work matters. It is a matter of life and death for the people we serve.”

For Ihab, WHO has been more than a workplace, it’s been a lifeline. “Together, we’ve strengthened the backbone of operations, ensuring the flow of medical supplies to health facilities and partners across Gaza.” Ihab says the support he received allowed him to grow, to lead and “to keep pushing forward whatever the circumstances”.

“I want the world to know that the true heroes of Gaza are ordinary people, with hopes, fears and families to protect.”

Masood Khan

From polio survivor to vaccinator in Peshawar

“I couldn’t walk because of polio, so my brother used to carry my bag to school every day. When other children were playing at school, I could only watch them and feel sad. It was very disappointing. That is why I took up the vaccinator course to help protect children from this crippling disease called polio.”

Growing up with a polio disability, Masood found strength and purpose in serving his community and protecting children from the disabling disease that has shaped his life. He is one of over 14 000 vaccinators supported by WHO as part of the Pakistan Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI). He has been working as a vaccinator for 10 years, providing routine vaccinations, including polio drops, to children at the Civil Dispensary in the Garhi Atta Muhammad area of Peshawar.

Masood’s job as a vaccinator is a central plank of Pakistan’s drive to eradicate polio in Peshawar, a poliovirus hotspot and hub of further transmission. His activities supplement the work of over 400 000 volunteer polio vaccinators who, multiple times a year, go from door to door immunizing more than 45 million children against paralytic polio.

Masood’s job as a vaccinator is a central plank of Pakistan’s drive to eradicate polio in Peshawar, a poliovirus hotspot and hub of further transmission. His activities supplement the work of over 400 000 volunteer polio vaccinators who, multiple times a year, go from door to door immunizing more than 45 million children against paralytic polio.

Masood navigates the narrow streets of Peshawar – and his daily work – with the help of family and friends who have been a solid support throughout his life. Since he cannot walk long distances, he works at a fixed EPI site. A friend brings him to work and drops him home every day on a motorbike.

Masood's job as a vaccinator is a central plank of Pakistan's drive to eradicate polio in Peshawar, a poliovirus hotspot and hub of further transmission. His activities supplement the work of over 400,000 volunteer polio vaccinators who go from door to door, immunizing more than 45 million children against paralytic polio.

“I am grateful to the communities that cooperate and bring their children for vaccination. I am also grateful to my family, who have always stood by me and supported me in my decisions,” says Masood.

At the Civil Dispensary, Masood vaccinates an estimated 3000 children every year. But his role goes beyond vaccination. He also serves as a powerful advocate for immunization. When parents hesitate or refuse vaccines for their children, Masood steps in, not just as a health worker but as someone who has endured the harsh reality of a preventable lifelong disease.

At the Civil Dispensary, Masood vaccinates an estimated 3000 children every year. But his role goes beyond vaccination. He also serves as a powerful advocate for immunization. When parents hesitate or refuse vaccines for their children, Masood steps in, not just as a health worker but as someone who has endured the harsh reality of a preventable lifelong disease.

“I encourage parents to ensure that their children are vaccinated on time so that they can prevent these diseases. Vaccine-preventable diseases sometimes have no treatment and can result in total disability or death. I give myself as an example: Look at me, I say, and the pain I endure. If you don't vaccinate, the same could befall your child, leaving their life incomplete.”

Masood Khan: From polio survivor to polio vaccinator

Masood Khan grew up in Peshwar, Pakistan🇵🇰, carrying the heavy burden of polio, a burden heavier than his school bag, which he couldn’t carry due to his weakened muscles and paralysis. But instead of letting the disease define him, Masood turned his pain into purpose. He enrolled in a vaccination course and became a vaccinator to protect every child from multiple diseases, including the one that had paralyzed him.

He persuades hesitant parents, reminding them that vaccination can spare their children the hardships he endured.

Dr Ahmad Al Mulla, Qatar

Fighting for a tobacco-free future

For over 20 years, Dr Ahmad Al Mulla has been at the forefront of Qatar’s tobacco control efforts. As Director of the Tobacco Control Centre at Hamad Medical Corporation, he has built one of the strongest cessation programmes in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. His approach is less about rules and policies, and more about people, prevention and a determination to fight what he calls “a quiet epidemic”.

For over 20 years, Dr Ahmad Al Mulla has been at the forefront of Qatar’s tobacco control efforts. As Director of the Tobacco Control Centre at Hamad Medical Corporation, he has built one of the strongest cessation programmes in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. His approach is less about rules and policies, and more about people, prevention and a determination to fight what he calls “a quiet epidemic”.

Tobacco control is about saving lives, says Dr Ahmad.

“Tobacco use is one of the leading preventable causes of disease. Every person we help quit, every life we save, reflects back on the health of the whole country.”

It’s the personal victories that keep him motivated. One of Dr Ahmad’s favourite memories is running into a former patient at a wedding – someone who had been smoke-free for ten years.

“ He introduced me to his family saying, ‘This is the doctor who helped me quit smoking’. He had become an ambassador for tobacco control without even knowing it.”

In a field where change often happens slowly, it is moments like this that keep Dr Ahmad motivated. From juggling limited budgets to combatting the relentless marketing of new tobacco products, his work has only grown more complex. Yet he is as determined as ever. He stresses how important it is to enforce existing laws, especially to protect young people, and tirelessly advocates for decision-makers to turn commitments into real action.

Under his leadership, the Tobacco Control Centre – a WHO collaborating centre – is shaping national and regional progress. The excellence of its work has gained international recognition, including the WHO Director General’s World No Tobacco Day Award in 2025 and multiple WHO accreditations. The certificates on the wall and trophies on display are a testament to years of dedication and innovation, and the results they achieve.

Lives changed, families made healthier, and the belief that every single person who quits tobacco use is a success worth celebrating: these are the things that underpin Dr Ahmad’s unwavering commitment to promote a smoke-free future.

Sabiriin Mohamed Noor

The midwife saving mothers and newborns in Mogadishu

Sabiriin Mohamed Noor works at Banadir Hospital, Somalia’s largest public hospital, where mothers arrive every day with life-threatening complications. At 25 years old, Sabiriin delivers babies, stabilizes women facing severe bleeding and gives newborns in distress a fighting chance at life. She does so with courage, compassion and skill.

Sabiriin Mohamed Noor works at Banadir Hospital, Somalia’s largest public hospital, where mothers arrive every day with life-threatening complications. At 25 years old, Sabiriin delivers babies, stabilizes women facing severe bleeding and gives newborns in distress a fighting chance at life. She does so with courage, compassion and skill.

“My decision to become a midwife came from a painful experience I witnessed as a young girl in form three”, says Sabiriin

“A pregnant woman in my neighbourhood went into labour. There were very few hospitals in Mogadishu at the time, and maternal services were extremely limited.”

“Most women preferred traditional birth attendants but the attendant the expectant mother trusted was not available that day, recalls Sabiriin.”

“I was the closest person to her, but I had no skills or knowledge to help. I called an ambulance and went with her to the hospital. Sadly, the baby did not survive and the mother’s uterus ruptured, leaving her unable to have another child.”

The experience shaped Sabiriin’s life. It was the moment she promised herself she would become a midwife and help mothers and children in Mogadishu.

It was a promise she kept. After graduating from university, Sabiriin began her journey. With training and support from WHO, she gained the confidence to act quickly in emergencies, and the supplies to provide safe, quality care.

“Today, she says, I am proud to serve my community.”

“IWhen a mother and her baby leave this hospital alive and healthy, that is the greatest reward for me.”

Sabiriin’s story reflects the resilience being built within Somalia’s fragile health system through the joint efforts of the Government, WHO and other partners. Banadir Hospital stands as a beacon of hope for thousands of families in Mogadishu and beyond, while dedicated health workers such as Sabiriin help to build safer and healthier communities.

WHO is indebted to all the health workers, community workers and partners who help deliver essential services to some of the most vulnerable people in the world. Such delivery depends on the dedication, compassion and tireless efforts that Sabiriin exemplifies. Her journey from determined student to frontline health hero serves as an inspiration to all.

Majid Al-Qahtani

Building a regional model of excellence

As Director of Healthy Cities Affairs at the Ministry of Health, Mr Majid Al-Qahtani has played a pivotal role in building integrated community health systems that contribute to achieving Saudi Vision 2030’s aspirations for healthier, more resilient and sustainable communities.

As Director of Healthy Cities Affairs at the Ministry of Health, Mr Majid Al-Qahtani has played a pivotal role in building integrated community health systems that contribute to achieving Saudi Vision 2030’s aspirations for healthier, more resilient and sustainable communities.

The Healthy Cities programme in Saudi Arabia integrates health promotion into all aspects of urban development and community life. Based on standards set by WHO for healthy cities, Saudi Arabia has built an integrated system focused on developing the urban environment, improving quality of life and encouraging communities to actively participate in adopting healthier, sustainable lifestyles.

With more than 12 years of experience in the field, Mr Al-Qahtani helped lay the programme’s foundations across the Kingdom’s cities, taking into account their diverse population structures and differing health challenges. His success is due to an exceptional ability to communicate effectively with provincial and city coordinators and build a cohesive network that supports the exchange of experiences and unifies efforts towards achieving common goals.

The accreditation process in Saudi Arabia began in 2018, when Diriyah was recognized as the first Healthy City in the Kingdom. Since then, 16 cities have been certified, including Jeddah and Madinah which became the first 2 Healthy Megacities in the Region, benefiting millions of residents. In addition, WHO recognized the Kingdom's Healthy Cities programme as a collaborating centre.

Mr Al-Qahtani’s frequent field visits to cities, followed by the preparation of detailed and comprehensive reports, has been central to building local capacities and strengthening institutional and community work. His focus is on empowering national staff, developing monitoring and evaluation tools and providing the necessary technical support for programmes implemented on the ground.

Evaluating the performance of supporting sectors; implementing annual action plans to ensure sustainability; preparing comprehensive descriptions of the unique characteristics of each Healthy City and training staff in international accreditation standards: the fruits of these efforts are evident in the tangible successes achieved by the cities participating in the programme.

Thanks to the balanced leadership and strategic planning overseen by Mr Al-Qahtani and his team, Saudi Arabia’s Healthy Cities Programme has become a national and regional model for health promotion and sustainable development.

Khaled Al-Hallaq

Protecting children in Idlib

Each morning, Amer fastens the straps on his vaccine cooler and sets out. While the destinations vary – a schoolyard, a tent in Al-Burj camp, a dusty side road – his goal is always the same. To make sure no child is left unprotected.

Each morning, Amer fastens the straps on his vaccine cooler and sets out. While the destinations vary – a schoolyard, a tent in Al-Burj camp, a dusty side road – his goal is always the same. To make sure no child is left unprotected.

Khaled is a vaccination supervisor at Al-Sham Paediatric Specialty Hospital. He oversees 2 teams. One is based at the hospital, the second is a mobile team covering the area between Batbu and Sarmada in Al Dana sub-district, Idlib.

“It’s not just about giving vaccines,” says Khalid. “It’s about building trust, raising awareness, reassuring anxious parents amid the uncertainty of displacement and making sure no child is left behind.”

In the early days, many parents were hesitant. “There were rumours and misinformation,” says Khalid Al-Hallaq. “Some had never heard of the vaccines before. Others were scared because of what they had read online or heard from neighbours.”

Week after week, team members spoke to families, patiently explaining the benefits of vaccination and answering questions. Over time, things started to change. “Now, parents call us when their child misses a dose. They know us. They trust us.”

Week after week, team members spoke to families, patiently explaining the benefits of vaccination and answering questions. Over time, things started to change. “Now, parents call us when their child misses a dose. They know us. They trust us.”

“We follow up with every child. If someone misses a dose, we go back. If they have moved, we try to find them again.”

“Our digital tracking system has been crucial. It allows us to check which families have missed appointments and support those who have lost their vaccine cards. We track each child’s doses to make sure no one is left behind.”

Khalid remembers one family in particular: displaced from Homs, they were living in Al-Burj camp. The father, Jameel, had 15 children, several of whom had missed their vaccines. “Once they settled in the camp, we visited them. We checked all their records and made sure each child was up to date.”

Khalid remembers one family in particular: displaced from Homs, they were living in Al-Burj camp. The father, Jameel, had 15 children, several of whom had missed their vaccines. “Once they settled in the camp, we visited them. We checked all their records and made sure each child was up to date.”

Khalid smiles at the memory. “Every dose we give is a promise,” he says. “A promise of protection, of possibility. And a step towards rebuilding trust – not just in health care, but in the future.”

The services provided by the team are part of a joint effort involving the Ministry of Health, UNICEF, WHO and health partners, with support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Gates Foundation. In Idlib and Aleppo, more than 80 immunization centres and outreach teams operate with this collective support. As Syria starts to recover from years of instability, these locally led efforts mark an important step towards a more integrated and nationally supported health system. At its heart are people like Khaled.

Remembering Dr Leila Hamdal-Nil – a true Hero of Health for Sudan

As Head of Response at the Federal Ministry of Health, Dr Leila Hamdal-Nil led Sudan’s emergency response through two and a half years of conflict. She carried this responsibility not just as a duty, but with passion, courage, and deep personal commitment.

As Head of Response at the Federal Ministry of Health, Dr Leila Hamdal-Nil led Sudan’s emergency response through two and a half years of conflict. She carried this responsibility not just as a duty, but with passion, courage, and deep personal commitment.

At the very start of the conflict, she returned to Sudan at great personal risk to serve her people. She traveled tirelessly across all accessible states, coordinating life-saving responses for host communities and displaced families alike.

Dr Leila was also a steadfast supporter of WHO’s emergency operations. She personally followed up on critical approvals, secured passage for shipments, and made sure supplies reached the right place at the right time. She understood that every box of medicine, every timely delivery, meant lives saved.

She was more than a Director. She was a “Kandaka” - a woman of strength and dignity. A passionate, compassionate leader. A true Face of Health for Sudan.

Dr Leila will be greatly missed, but her legacy lives on in the countless lives she protected and the health workers she inspired.

Thank you to every single person working tirelessly to support the health of the people of Sudan.

Mohamed Habib

Acting to save lives

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), the leading cause of death in Tunisia, account for more than 30% of annual mortality. While tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity and high stress levels contribute to the problem, traditional health campaigns have often struggled to inspire long-term behavioural change.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), the leading cause of death in Tunisia, account for more than 30% of annual mortality. While tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity and high stress levels contribute to the problem, traditional health campaigns have often struggled to inspire long-term behavioural change.

In a bid to put culture at the heart of health promotion, Tunisia has adopted a new, collaborative approach. With support from WHO, and within the framework of the HEARTS project, the Ministry of Health and the Directorate of Basic Health Care partnered with the Ministries of Culture, Education and Youth, civil society organizations and academic experts to co-design a community-based social and behavioural change programme.

By mobilizing theatre and cultural activities to raise awareness, promote dialogue and encourage healthier lifestyles, and by training youth and adult leaders as health-culture mediators, the initiative builds community capacity to take ownership of health.

Tunisian actor and director Raouf Ben Yaghlane leads the cultural component of the initiative, transforming health messages into engaging performances. The multisectoral partnership has staged workshops and plays in schools, youth centres and public spaces, strengthening inclusivity by reaching new audiences.

As a result of the programme, young actor Mohamed Habib Boujemaa has become a passionate advocate for public health. With the programme’s support, Habib helped create a play on tobacco addiction.

“Theatre made me aware of my role in society. I realized that I could influence behaviour and support healthier choices by using my talent on stage, says Habib.”

The recorded version of the play has reached more than 45 000 online viewers. By avoiding lectures and concentrating instead on the emotional and social dimensions of smoking, the messages contained in the performance resonate more strongly with audiences. “Art delivers the message, supports health and awakens people,” says Habib.

This is exactly the kind of ripple effect the Ministry of Health in Tunisia and WHO aim to achieve, empowering communities and amplifying young voices to help ensure health messages spread far beyond conventional platforms.

By integrating culture into health promotion, Tunisia is not only raising awareness of CVD. It is building sustainable, citizen-driven movements for well-being.

Nevien Attalla

Delivering hope to millions of people

Nevien Attalla is Operations Manager at the WHO Logistics Hub in Dubai. With a background in pharmacy, she moved from being a microbiological instructor to the retail field before joining the United Nations Humanitarian Response Depot (UNHRD) in 2012.

Nevien Attalla is Operations Manager at the WHO Logistics Hub in Dubai. With a background in pharmacy, she moved from being a microbiological instructor to the retail field before joining the United Nations Humanitarian Response Depot (UNHRD) in 2012.

“This is where I found my true passion – humanitarian response,” says Nevien. “Then, in 2015, the WHO Dubai Hub was established, providing me with many valuable experiences in the humanitarian sector.”

Humanitarian work, by its nature, involves working in unpredictable environments. Managing pharmaceutical supplies in such settings presents unique challenges, from sourcing from limited suppliers and maintaining proper storage conditions and temperature controls for every item to optimizing prepositioned supplies and navigating the logistics associated with countries’ different regulatory regimes.

“I have learned to be resilient and adaptable, to find creative solutions to problems while remaining focused at all times. Humanitarian response depends on collaboration with diverse groups, local authorities, governmental agencies and other humanitarian organizations within and outside the UAE. This taught me the importance of effective communication, cooperation and coordination to achieve common goals in a culturally sensitive and respectful manner.”

The COVID-19 pandemic response was a particularly challenging time for Nevien: “While many people were able to work remotely and stay safe at home, our team had to be physically present, and for longer hours, to ensure the timely delivery of aid. Our workload increased exponentially, in tandem with concerns about the health and the safety of our team.”

While being away from home for longer hours, facing increased personal risks, exposing her husband and 3 children to the same, compounded the stress of her work, Nevien’s determination never wavered.

“Seeing the WHO logistics hub in Dubai deliver hope to millions of people in need of health aid across all WHO regions, but particularly during the Gaza crisis, and witnessing the prompt delivery of lifesaving medicines to support WHO, UNRWA and other agencies” has taught her invaluable life lessons, says Nevien.

Among those lessons – perhaps the most important – is that you never, ever give up.

Faten Faraj Ba Mahysoun

“Every life is worth the rush”

Faten Faraj Ba Mahysoun heads the Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care Department at the Mother and Child Hospital in Mukalla, Yemen. Her role does not involve delivering babies or directly managing medical cases, though the people whose job it is to do those things depend on her.

Faten Faraj Ba Mahysoun heads the Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care Department at the Mother and Child Hospital in Mukalla, Yemen. Her role does not involve delivering babies or directly managing medical cases, though the people whose job is to do those things depend on her.

Faten’s role is to ensure that physicians and nurses are available when and where they are needed. To ensure that there is a supply of oxygen. To keep emergency pathways clear.

Faten’s role is to ensure that physicians and nurses are available when and where they are needed. To ensure that there is a supply of oxygen. To keep emergency pathways clear.

When a mother clutches her belly and is in need of lifesaving support, when a newborn stalls in taking its first breath, it is Faten’s voice that cuts through the chaos, that moves the needed resources in seconds not hours.

In the high-pressure environment of the Obstetric and Newborn Care Department, the margin for error isn’t razor thin. There is no margin. Not in a hospital where – like many facilities in Yemen – the electricity can fail, stocks run low and the flow of patients never stops.

Her job is about timing. When a delivery turns critical, when a newborn needs urgent resuscitation, there is no space for delay. She monitors incoming cases, escalates alerts. She keeps departments aligned, so they can act fast. Behind the scenes, she is the one who responds to pressure with precision.

Calm, focused, ready. These are the watchwords that guide her every move.

Faten’s impact isn’t measured in reports. How can it be? It is measured in the heartbeat of every child who leaves the hospital in its mother’s arms.

“You don’t forget the sound of a baby crying after a long silence, she says. That moment makes everything worth it.”

“Every minute matters. Every life is worth the rush.”

In a country facing some of the world’s toughest health challenges, Faten shows that health heroes don’t always wear scrubs. Sometimes they carry a radio and a clipboard, and run the rooms where lives are saved.