Moaayd “These communities face a lot of violations… We should be providing health services at least three times a week, but we cover communities in three districts of the Jordan Valley and there is only so much we can do.” Moaayd

Moaayd is the driver of a mobile clinic for the Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS) operating in the Jordan Valley of the West Bank. He has been part of the team for 10 years, working with communities in remote areas that depend on mobile clinics for access to primary health care. The communities face obstacles to planning and development, demolition orders that make their lives and livelihoods precarious and uncertain, and the under-provision of basic services.

Bank. He has been part of the team for 10 years, working with communities in remote areas that depend on mobile clinics for access to primary health care. The communities face obstacles to planning and development, demolition orders that make their lives and livelihoods precarious and uncertain, and the under-provision of basic services.

“These communities face a lot of violations. The Red Crescent tried four times to assist with building six houses to provide emergency shelter, but each time the houses were demolished… We should be providing health services at least three times a week, but we cover communities in three districts of the Jordan Valley and there is only so much we cando. To reach all communities, the mobile clinic needs to serve two or three communities at a time. Here in Khirbet Al-Meiteh, some people need to walk half an hour from nearby communities to reach us,” Moaayd comments.

Khirbet Al-Meiteh is a community served by Moaayd’s team, located in Wadi Al-Maleh in the northern Jordan Valley, in the governorate of Tubas. The community of 300 people is situated in Area C, where Israel maintains civil and military control. It lies in an area designated as a firing zone, meaning severe restrictions on planning and development, including for roads, schools, and health facilities. Residents rely on agriculture and pasture for their livelihoods, which are threatened by land confiscations and expanding settlements in the surroundings. There is lack of adequate protection for the communities, who experience settler- and occupation-related violence and who face loss of livelihoods due to destruction of crops and attacks against livestock.

The nearest permanent primary care facility is in Tubas, which would be around 30 minutes away by car without unpredictable checkpoint delays. Many in Khirbet Al-Meiteh do not have a vehicle, so the mobile clinic serves as a vital lifeline for the community. However, the community remains underserved, with expansion of service provision and establishment of permanent facilities needed.

“The mobile clinic covers part of the needs for our community in Wadi Al-Maleh,” says Mahdi, a member of the community council. “However, we desperately need a permanent facility. We tried to build two rooms last year to use them as clinics, but Israeli forces demolished the rooms. We’ve been unable to build them again due to lack of funding.”

The PRCS clinic Moaayd works for covers Tubas, Nablus, and Jericho. Each community or cluster of communities served by the mobile clinic receives one or two visits a month. The clinic itself operates five days a week, providing primary health care on three days and services for women’s health on two days. The team consists of a driver, nurse and doctor, with a social worker joining the team on occasion. Recently, the PRCS community service programme was able to offer additional support to the communities in Wadi Al-Maleh, training youth in the provision of first aid to offer immediate support to injured persons and responding to the high numbers of casualties during demonstrations against settlement expansion.

experience too. When the community faced demolitions, I was there to help. Despite all our efforts, we need to do a lot more. I’m happy we can provide at least basic health services, but our communities deserve comprehensive health care like all people.”

experience too. When the community faced demolitions, I was there to help. Despite all our efforts, we need to do a lot more. I’m happy we can provide at least basic health services, but our communities deserve comprehensive health care like all people.”

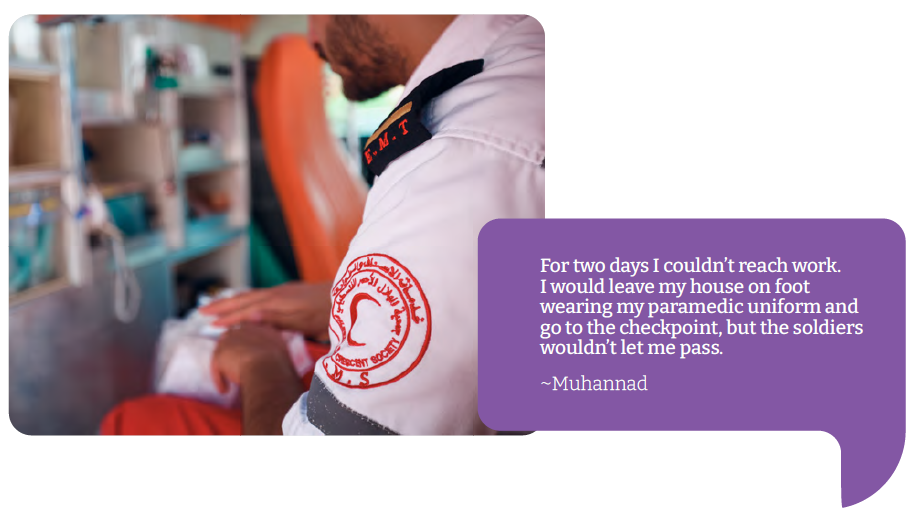

Muhannad “For two days I couldn’t reach work. I would leave my house on foot wearing my paramedic uniform and go to the checkpoint, but the soldiers wouldn’t let me pass.” Muhannad

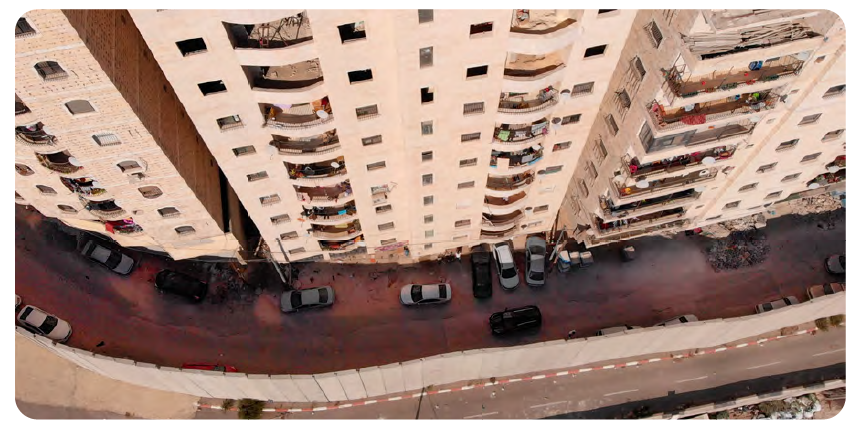

From 8 to 11 October, Israel enforced a near-complete closure of Shu’fat refugee camp and adjacent areas of Anata. The area, home to refugees and non-refugees in east Jerusalem, is surrounded by Israel’s separation barrier, which takes the form of an 8- to 9-metre-high concrete wall enclosing the camp. In addition to the existing checkpoint west of the camp, Israeli forces established a flying checkpoint to the east, controlling all movement in and out.

home to refugees and non-refugees in east Jerusalem, is surrounded by Israel’s separation barrier, which takes the form of an 8- to 9-metre-high concrete wall enclosing the camp. In addition to the existing checkpoint west of the camp, Israeli forces established a flying checkpoint to the east, controlling all movement in and out.

The closure of the camp resulted in severe restrictions on access to health care for the population of 130,000. Ambulances, patients, and health care workers were prevented passage at checkpoints. Muhannad, a paramedic with the Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS), was affected and unable to reach his place of work.

“For two days I couldn’t reach work. I would leave my house on foot wearing my paramedic uniform and go to the checkpoint, but the soldiers wouldn’t let me pass.”

With violence and confrontations inside the camp, Muhannad put his skills to use helping people as he could: “I have a paramedic bag from PRCS. I used to take my bag and go to help anyone who had been injured. Yet there was no way to transport them to hospital, the injured had to be treated inside homes or in small clinics. I was exposed when I was caught trying to provide medical assistance to some youth. Some soldiers came from behind and surrounded us. Even though I was wearing my vest and they could see I was holding a first aid kit I was targeted. I hid behind a piece of wood but we were still attacked with rubber bullets until a car came and helped me get out of the area.”

During the period, WHO documented the prevention of access of six ambulances attending to cases with seizures, an injury, chest pain, abdominal pain, a patient requiring kidney dialysis and a woman in delivery. There were an additional ten instances documented of severe delays in access for ambulances. Meanwhile, patients requiring access to primary care and outpatient care outside the camp were prevented from passage at checkpoints, along with health personnel requiring access to places of work.

Obstacles to movement affecting the camp are longstanding. The checkpoint to the west can only be used by residents of Shu’fat refugee camp with east Jerusalem residency. Individuals living in Shu’fat refugee camp with West Bank IDs and approved permits to reach east Jerusalem or Israeli hospitals for health care would have to exit to the east and enter the city via Qalandia checkpoint.

As well as obstacles to movement, residents of Shu’fat refugee camp experience chronic under-provision of municipal services and fragmented provision of health care. Lax building regulations mean that the area is very densely populated, with residents complaining about the quality of housing and overcrowding. Rubbish piles up in the streets due to infrequent refuse collection. Meanwhile, there is differential access to health care for residents with east Jerusalem IDs versus West Bank IDs, as well as for refugees compared to non-refugee residents. During a meeting with UN representatives at the time of the closure, community representatives called for stronger protection from the international community and an end to the severe restrictions on access to the camp.

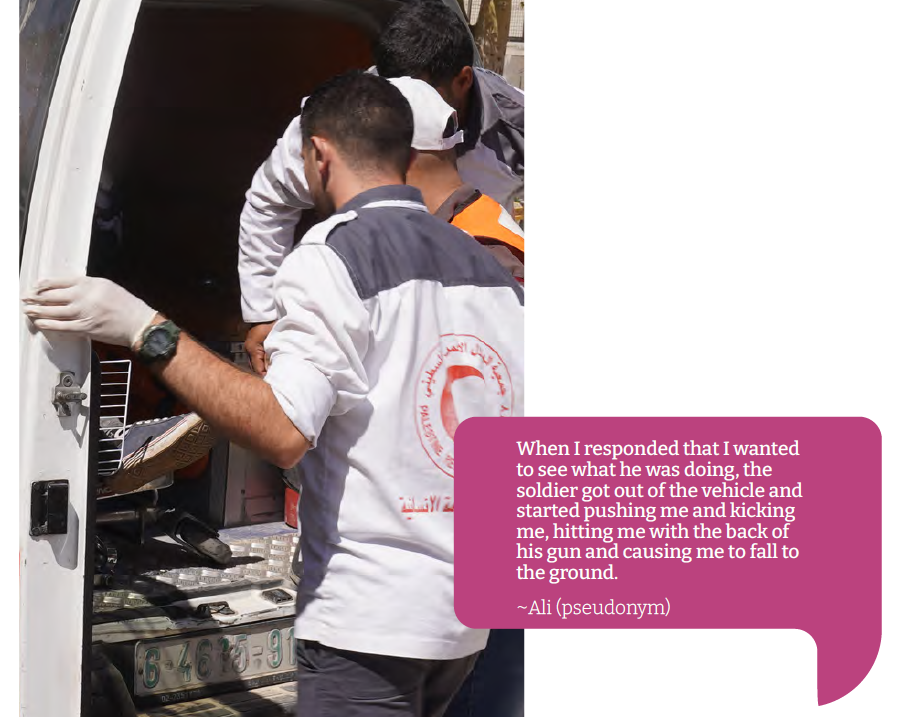

Ali “When I responded that I wanted to see what he was doing, the soldier got out of the vehicle and started pushing me and kicking me, hitting me with the back of his gun and causing me to fall to the ground.” Ali (pseudonym)

On 2 October 2022, a Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS) ambulance crew travelled to Beit Furik near Nablus, to provide first aid to persons injured during demonstrations against settlement expansion and incursions in the village, which is in the north of the West Bank.

aid to persons injured during demonstrations against settlement expansion and incursions in the village, which is in the north of the West Bank.

Ali was driving the ambulance, while his colleague Omar1 sat beside him. They crossed the checkpoint leading to Beit Furik without obstruction. However, as the ambulance approached the entrance to the village the crew was confronted with a temporary (flying) checkpoint comprising Israeli soldiers and border guards.

“The soldiers aimed their guns towards us and were shouting at us, ordering us to stop,” said Ali, the driver. “I was driving very slowly, as we are used to doing in situations like this, and stopped behind one of the military jeeps. A soldier came to the window and told me to turn the engine off and give him the keys. He was banging at the window with the back of his gun. I tried to explain that we had information that there were people injured and we needed to reach them.

“After switching off the engine, the soldiers insisted on searching the vehicle. I offered to go to the back of the vehicle with the soldier to open the ambulance for him, but he refused. We are used to going with the soldiers to open the door. They usually want us to be in front of them when they search a vehicle, but this soldier insisted on going alone. Because of this, I was afraid he might try to plant a weapon or a knife on the vehicle and make an accusation against us. I wanted to see what he was doing, but another soldier stood by my door, aiming his weapon at me, and preventing me from leaving the vehicle or seeing behind.

“The ambulance vehicle automatically locked when the soldier tried to open it. He then shouted towards me ordering me to open the backdoor, which I did. I left the ambulance and went towards the backdoor. At this point the soldier shouted at me again, asking why I was there. When I responded that I wanted to see what he was doing, the soldier got out of the vehicle and started pushing me and kicking me, hitting me with the back of his gun and causing me to fall to the ground.

“Omar came out of the vehicle and tried to help me. Another soldier beside the ambulance came and started pushing Omar, while a further 3 soldiers joined and were surrounding us and pushing us away from the ambulance.”

At the point that Ali and Omar had been pushed away from the vehicle, someone in the nearby demonstration began recording what was happening in a video on their phone. The video shows the soldiers pushing, kicking and beating the paramedics before they are both made to kneel on the ground.

“When we were on the ground, someone was trying to call me. I answered the call on speaker so that the person on the line would know we were in danger. That person contacted the Palestinian Coordination Office, who arrived on site shortly afterwards. Following negotiation, we were released. Another ambulance came to take Omar to hospital for treatment, while I provided information to the officer from the Coordination Office. I then drove myself to hospital.”

As a result of the attack, Ali sustained injuries to his leg including tear of a cartilage in his knee, requiring treatment for the pain and physiotherapy. He returned to work after 40 days.

“Even after my injury, I will go back to the field. Even if it means that something can happen to me, this is our duty. We were raised this way; this is who we are. It’s not the first time I was exposed to violence from soldiers. I worked during the Second Intifada, when we were fired at with live ammunition. We had a female patient in the ambulance at the time. The violations against us have continued all these years. We are still prevented from reaching injured people, pushed around by soldiers, and shot at. Our safety depends on the mood of the soldiers.”

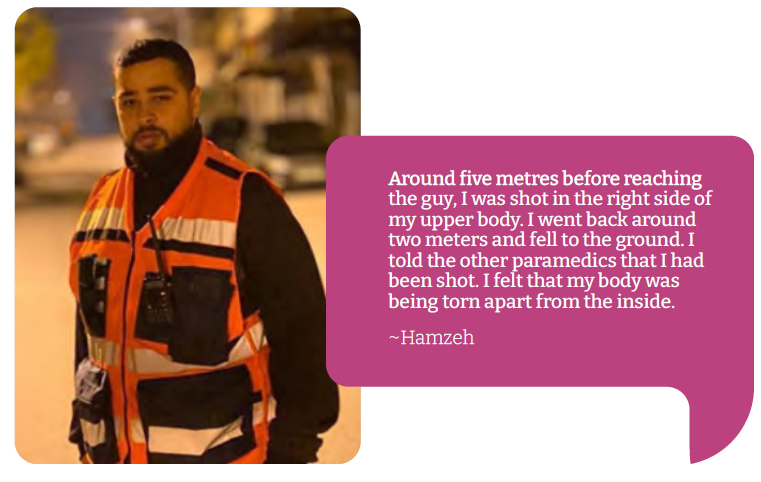

Hamzeh “Around five metres before reaching the guy, I was shot in the right side of my upper body. I went back around two meters and fell to the ground. I told the other paramedics that I had been shot".

27-year-old Hamzeh Abu Hajar is a volunteer paramedic with the Palestinian Medical Relief Society (PMRS).

In 2022, with increasing escalations across the West Bank, Hamzeh began volunteering as a PMRS first responder.

“Every time the Israeli forces would raid Nablus Old City, I would join the field team. PMRS cars would drive us to different locations where people were injured and needed our help. I always made sure to wear my vest before leaving the house, while PMRS made sure we were all wearing vests by the time we reached a location with injured people… At first, wearing the paramedic vests made us feel protected. However, as the confrontations increased the occupation forces stopped distinguishing between paramedics, journalists, and others. We all feel or show fear in different ways. Of course, I was scared when going into the field, but it wasn’t the kind of fear that would prevent me from going to help the people who depended on us.”

At around 8am on the morning of Friday 30 December, Israeli forces raided Nablus Old City. Hamzeh was called to the field to support treating the injured.

“I heard calls to help with an injury near my location. I immediately went to respond, and there were another two paramedics behind me. Around five metres before reaching the guy, I was shot in the right side of my upper body. I went back around two meters and fell to the ground. I told the other paramedics that I had been shot. I felt that my body was being torn apart from the inside. I was on the ground for several minutes until Al Razi ambulance [a private ambulance] reached me. A sniper had been shooting between the two ambulances on site and me.”

The second ambulance had been from the Palestine Red Crescent Society, which was obstructed from reaching Hamzeh. After Al Razi ambulance reached him, they transferred him to hospital. The ambulance tried to exit via the western route to Rafidia Government Hospital but was again obstructed by Israeli forces, which compelled the team to return and take a different route.

“I remember slipping in and out of consciousness. I vaguely remember being in the ambulance. I also remember my brother, doctors, some of my PMRS friends, and many other people surrounding me in the hospital. I was put in an emergency intensive care room when I reached the hospital and ten minutes later, I was transferred to the operating room.”

Hamzeh’s surgery took 4.5 hours. He stayed in the intensive care unit for 6 days, after which he was transferred to another ward for a further two days before being discharged home. The bullet had injured Hamzeh’s right lung and diaphragm, torn part of his liver and right kidney, and broken four of his ribs. He also suffered a bladder injury. After being shot, the bullet exited from his back, resulting in a tear of his muscle and an open wound around 20 to 25 centimetres in diameter. As a result of his surgery, Hamzeh had 40 stitches in his abdomen, while his back wound remains open and will require several months to heal.

Hamzeh is undergoing a slow recovery. He moves around the house and goes for follow up visits to the hospital every Tuesday. Because of his broken ribs he faces difficulties moving and sleeping. The injury of his lungs means he gets very tired whenever he tries to move around the house.

“Before my injury I witnessed some difficult cases working in the first response teams. I helped provide first aid to people who had very severe injuries. I even had to move people who had been killed. One of the hardest experiences was when I had to move a martyr who turned out to be my friend. I had been with him just a few hours before the raid. I was so shocked to see that it was my friend. Even these experiences didn’t prevent me from going back to the field. On the contrary, it gave me a stronger push to go and to support those in need, especially knowing that they depended on our help. I felt it was my duty to help them. After I fully recover, I plan to return. My mother is worried. She keeps telling me that she doesn’t want me to go back. She says the first time I was lucky, but we don’t know what will happen next time. Still, I plan to return.”