Khalid “He is a patient and has the same right as any person who wants to get treatment.”Khaled Riham, wife of Khalid

Khalid, 36 years old from Gaza city, has end stage kidney failure. For 16 years, he has been dependent on weekly haemodialysis (a procedure to remove waste and water from the blood, to perform the function of healthy kidneys).

(a procedure to remove waste and water from the blood, to perform the function of healthy kidneys).

In late 2022, Khalid required referral out of Gaza for vascular surgery so that he would be able to keep having lifesaving haemodialysis. Despite repeated surgeries in Gaza, doctors were unable to establish the vascular access needed for the procedure. At Makassed Hospital in east Jerusalem, Khalid was to receive an artificial blood vessel graft.

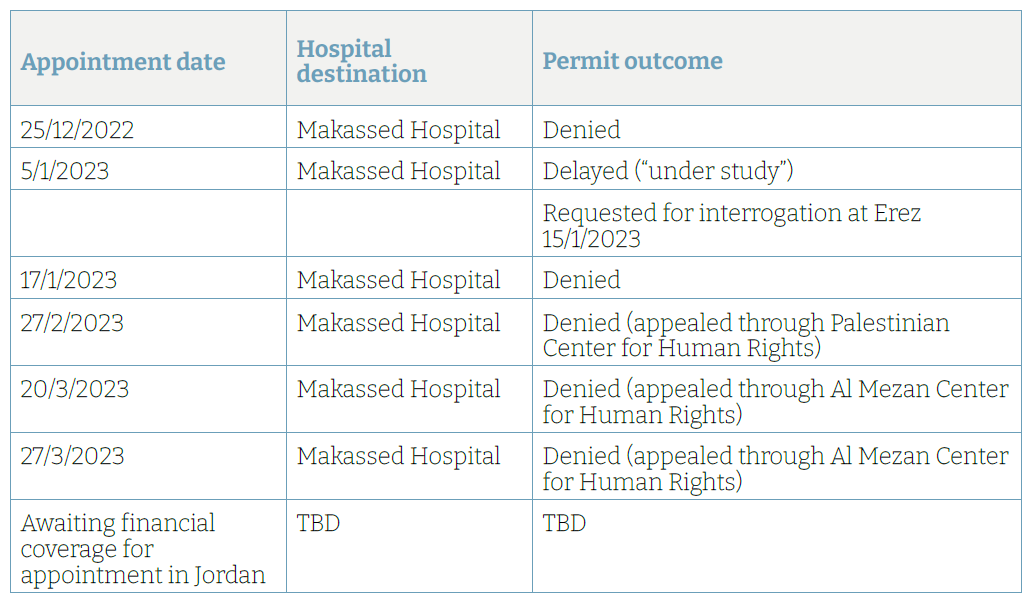

In total, Khalid made six permit applications to Israeli authorities. He was never approved a permit to reach Makassed Hospital but was instructed to change the destination and arrange a hospital appointment in Jordan after several appeals through human rights organizations and advocacy by the UN and partners. As of April 2023, Khalid was awaiting financial coverage from the Palestinian Ministry of Health for an appointment at a hospital in Jordan.

Table 1: Khalid’s hospital appointments, intended hospital destination, and permit outcomes

Amal “I don’t know why I am prevented. I have been waiting so long! I need to have this test so the doctor can make a clear diagnosis and give me proper treatment. I suffer and worry every day.”

Amal, 38 years old from Gaza city, was found to have a brain aneurysm (a potentially life-threatening ballooning of a blood vessel) in March 2022.

vessel) in March 2022.

On 5 June 2022, Amal was referred to An-Najah University Hospital in Nablus, in the West Bank, for brain catheterization and scan (angiography), a procedure not available in the Gaza Strip. She made one permit application for an appointment on 16 June that was delayed. Amal was approved a permit to travel on 3 August but following closure of Erez (Beit Hanoun) checkpoint by Israeli authorities on 2 August she was unable to exit the Gaza Strip to receive care.

Talking about the outcome of her first application, Amal said, “I don’t know why I am prevented, I have been waiting so long! I need to have this test so the doctor can make a clear diagnosis and give me proper treatment. I suffer and worry every day.

”Amal received a further hospital appointment at An-Najah University Hospital for 1 September. She was eagerly awaiting a text message from the Palestinian Health Liaison Office, hoping for a positive response, when WHO spoke with her the day before her appointment. She received the text at 5pm that day and called to ask, “I’ve just received a text message from the Liaison Office. It says under study. What does it mean?” After her initial disappointment, she received another message later that evening saying that she had been approved and could travel the next day.

Amal finally travelled and received the scan she needed. Doctors advised the best course of action would be to manage her condition with medicines, which she now takes daily. “I finally had the tests and I feel so grateful that I won’t need brain surgery after all. The doctors at An-Najah reassured me and prescribed me some medicines. They recommended that I will need follow up to keep an eye on things,” Amal said.

Table 1: Amal’s hospital appointments, intended destination, and permit outcomes

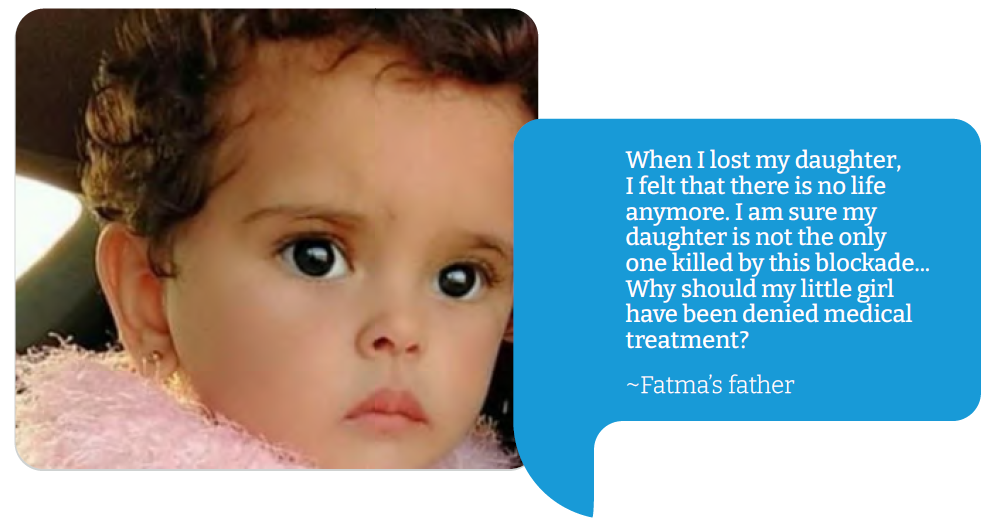

Fatma “When I lost my daughter, I felt that there is no life anymore. I am sure my daughter is not the only one killed by this blockade... Why should my little girl have been denied medical treatment?” Fatma’s father

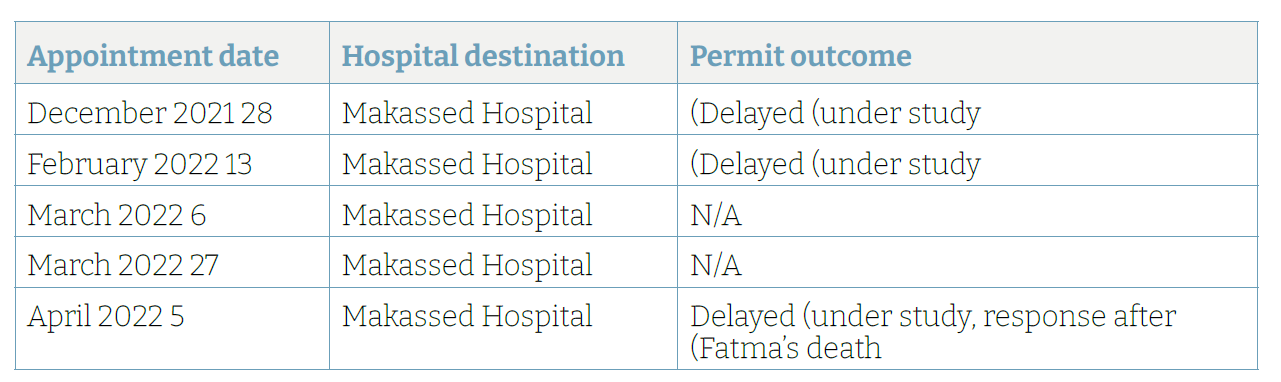

Fatma was a 19-month-old girl from Khan Younis in the Gaza Strip. She died on 25 March 2022 after she was delayed access to lifesaving cardiac surgery for nearly three months. Fatma was born with a congenital heart condition known as an atrial septal defect. She needed curative surgery at Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem and was required by Israel to obtain a permit to reach her hospital appointment. Her family applied three times for permits to reach hospital appointments on 28 December 2021, 13 February 2022, and 5 April 2022. She also received hospital appointments for 6 and 27 March, though at this stage no permit application was submitted by the Palestinian Health Liaison Office. Fatma’s father was told this was because there would not enough time for processing of the permit application.

lifesaving cardiac surgery for nearly three months. Fatma was born with a congenital heart condition known as an atrial septal defect. She needed curative surgery at Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem and was required by Israel to obtain a permit to reach her hospital appointment. Her family applied three times for permits to reach hospital appointments on 28 December 2021, 13 February 2022, and 5 April 2022. She also received hospital appointments for 6 and 27 March, though at this stage no permit application was submitted by the Palestinian Health Liaison Office. Fatma’s father was told this was because there would not enough time for processing of the permit application.

Since December 2021 and her first hospital appointment for heart surgery, Fatma’s health had been gradually deteriorating as her heart began to fail despite medical treatment and follow up by doctors in the Gaza Strip. “I was out the day Fatma died. My brother called and asked me to come home because Fatma was tired. They called an ambulance, which arrived before I got home. She died before she reached the hospital. We were in shock. I felt like I had died,” Fatma’s father said. “Everyone in the family loved Fatma dearly, she was so precious to all of us. Especially to my wife and me. She came to us after five years of fertility treatment. Our hearts are broken.” On 4 April, ten days after Fatma’s death, her family received a text message telling them that Fatma’s application for a patient permit remained under study.

Jalal, the father of Fatima added, “When I lost my daughter, I felt that there is no life anymore. I am sure my daughter is not the only one killed by this blockade. Of course, there are so many patients who have died. But why should my little girl have been denied medical treatment? Can anyone tell me why she deserved this? This killing must be stopped. This could happen to anyone who needs medical care.”

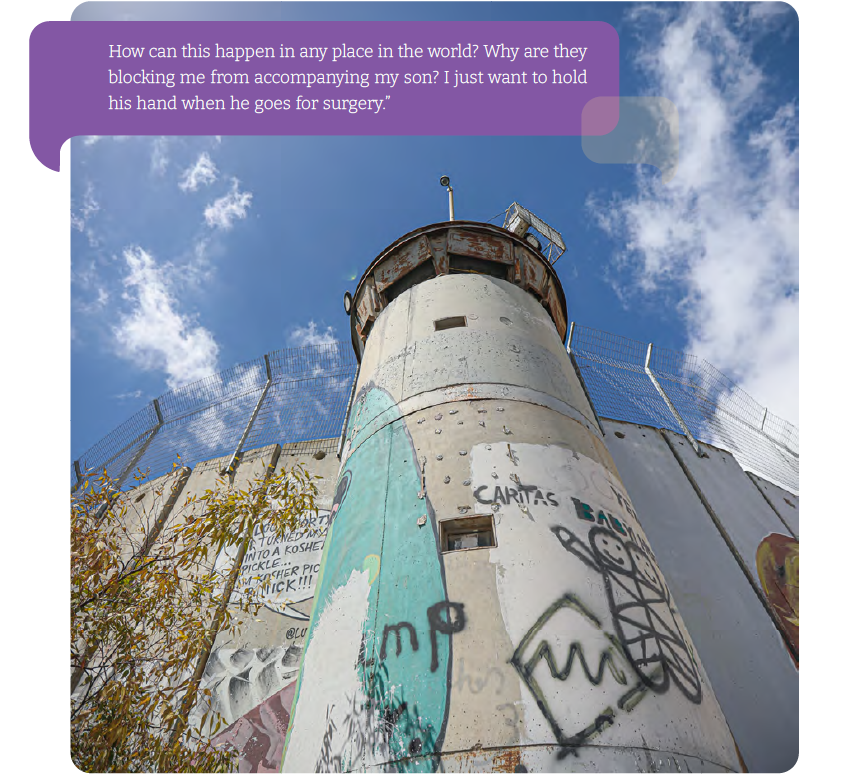

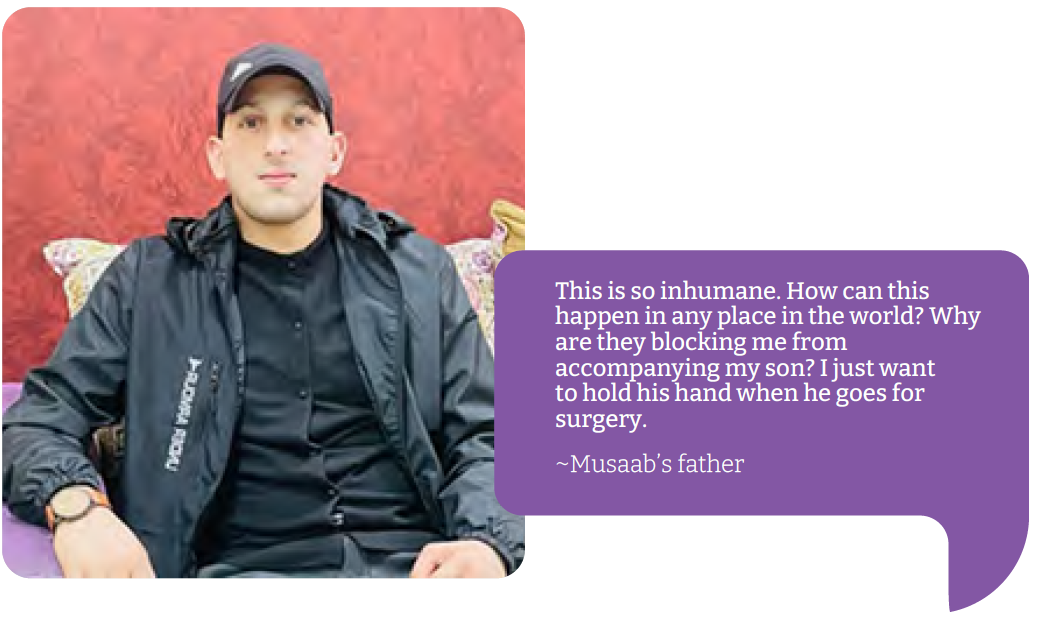

Musaab “This is so inhumane. How can this happen in any place in the world? Why are they blocking me from accompanying my son? I just want to hold his hand when he goes for surgery.” Musaab’s father

Musaab, 21 years old, was in the third year of his university studies in Nablus, in the north of the West Bank.

In the summer of 2022, he was diagnosed with a cancer called a synovial sarcoma in his left ankle. To confirm the diagnosis and to guide the best approach to his treatment, Musaab was referred to Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem for bone biopsy in June 2022, for an appointment on 6 July. Because of his West Bank ID, Israeli authorities required Musaab to obtain a permit to access East Jerusalem. He applied three times for a permit for his initial hospital appointment and was denied each time. The family were told that Musaab and his companions (different family members for each application) had been denied on security grounds. He eventually received a bone biopsy at Istishari Hospital in Ramallah, where he didn’t require a permit to reach his appointment.

Musaab was in Israeli prison from July 2020 to January 2021. It was during his detention that he started to feel pain in his left ankle. “He was given paracetamol, which didn’t help,” his father said. “He has been suffering a lot. He told me sometimes he felt as if his bone was being crushed.”

After his diagnosis, doctors considered to refer Musaab to Augusta Victoria Hospital, the major Palestinian cancer centre, in East Jerusalem. However, because he had been denied a permit to East Jerusalem previously, the doctors instead referred him to An-Najah University Hospital in Nablus, which meant he didn’t require an Israeli permit to reach care. Musaab received the chemotherapy he needed before he would undergo an operation. By November 2022, he was ready for surgery and his family applied for permits for him to reach Assuta Hospital in Tel Aviv. They wanted a private surgical consultation, to see the extent to which it would be possible to salvage Musaab’s leg. His three applications for a permit to reach two different appointments at the hospital were again denied.

Musaab’s father spoke with a doctor at Makassed Hospital to get advice on how to proceed. “He told me that repeatedly delaying surgery might cause bone erosion requiring leg amputation, God forbid.” The family had lost hope of obtaining a permit to access East Jerusalem, so Musaab’s father went to the Services Purchase Unit (SPU) of the Ministry of Health in Ramallah to request a change of destination to Jordan.

“Musaab and I travelled [to the Jordan border, the King Hussein Bridge] on 12 December. At the Bridge, we were asked to sit and wait. We waited about an hour, then an Israeli officer came out and asked us to go back to the West Bank. He said that we were both denied for security reasons. We refused to leave, and I requested to see the Mukhabarat [intelligence] officer. I insisted, telling them that my son has cancer and that he has the right to access health care. I asked them to let him go. After waiting another four hours, they decided to allow Musaab to cross to Jordan, but they made me return.” Although he crossed, Musaab missed his appointment at King Hussein Cancer Center in Amman, which had been for 12:30pm that day. The next available appointment was a week later.

“My son needs me beside him during these difficult times. We should see the doctor together so we can discuss the different options to help Musaab decide about the surgery.” Musaab’s father appealed through nongovernmental organizations Physicians for Human Rights Israel and Hamoked, as well as through a private lawyer, to get approval to travel to Jordan. He said, “This is so inhumane. How can this happen in any place in the world? Why are they blocking me from accompanying my son? I just want to hold his hand when he goes for surgery.”