Research article

O. Nafi1

التهاب المعدة والأمعاء بالفيروسات العَجَلية لدى الأطفال دون سن الخامسة في الكرك، الأردن

عمر علي نافع

الخلاصـة: إن إدخال اللقاح المضاد للفيروسات العَجَلية rotavirus قد أبْرَزَ أهمية تحديد الحاجة إلى تطعيم مجمل السكان. وقد كانت الغاية من هذه الدراسة التي أُجريَتْ في الأردن في العامَيْن 2007-2008 تحديد معدل وقوعات التهاب المعدة والأمعاء بالفيروسات العَجَلية وملامحه السريرية في الأطفال دون سن الخامسة الذين قُبلوا في المستشفى بسبب الإسهال. وبلغ عدد هؤلاء الأطفال 148 طفلاً، كان لدى 59 طفلاً منهم (%39.9) اختبار إيليزا ELISA إيجابي للفيروسات العَجَلية (بمقايسة الممتز المناعي المرتبط بالإنزيم)، وكانوا في الغالب من المجموعة العمرية التي تقلّ عن سنتين. ولوحظ ارتفاع هامشي في نسبة حدوث الحمَّى في حالات الإصابة بهذه الفَيْروسات بالمقارنة مع الحالات التي تخلو منها، كما كان أخفض معدل للعدوى في الشتاء. ولم تُسَجَّل أيَّة وَفَيات بين المجموعة المصابة بعدوى الفيروسات العَجَلية أو المجموعة غير المصابة بها. ولم يكن اللقاح المضاد للفيروسات العَجَلية مستخدماً في الأردن وقت إجراء الدراسة.

ABSTRACT The introduction of a rotavirus vaccine makes it important to determine the need for vaccination in a population. This study in Jordan in 2007–08 determined the incidence and clinical features of rotavirus gastroenteritis among children aged under 5 years admitted to hospital with diarrhoea. Of 148 children, 59 (39.9%) were ELISA-positive for rotavirus in stool samples, predominantly in the age group < 2 years. There was a marginally higher rate of fever in the rotavirus cases than the non-rotavirus cases. The lowest rate of infection was in winter. No deaths were recorded among the rotavirus or non-rotavirus groups. Rotavirus vaccine was not in use in Jordan at the time of the study.

La gastro-entérite à rotavirus chez les enfants de moins de cinq ans à Al-Karak (Jordanie)

RÉSUMÉ En raison de l’introduction d’un vaccin antirotavirus, il est important de déterminer le besoin de vaccination dans une population. La présente étude réalisée en Jordanie en 2007-2008 a permis d’identifier l’incidence et les caractéristiques cliniques de la gastro-entérite à rotavirus chez les enfants de moins de cinq ans hospitalisés pour une diarrhée. Sur 148 enfants, 59 d’entre eux (soit 39,9 %) avaient un test ELISA positif pour le rotavirus dans les échantillons de selles, principalement dans le groupe d’âge des moins de deux ans. Le taux de fièvre dans les cas à rotavirus était légèrement plus élevé que celui des cas sans rotavirus. Le taux d’infection le plus faible se situait en hiver. Aucun décès n’a été enregistré dans les groupes avec ou sans rotavirus. Le vaccin antirotavirus n’était pas utilisé en Jordanie au moment de l’étude.

1Department of Paediatrics, College of Medicine, Mutah University, Karak, Jordan (Correspondence to O. Nafi:

Received: 27/01/09; accepted: 08/04/09

EMHJ, 2010, 16(10):1064-1069

Introduction

Diarrhoea diseases are the second most frequent cause of death among young children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region [1,2] and rotavirus disease is the single most important cause of severe gastroenteritis in children throughout the world [3–5]. Globally about 30%–40% of hospitalizations and deaths due to diarrhoea among children under 5 years old, and about 5% of all child deaths, are attributed to rotavirus infection [1,6]. It occurs as a sporadic seasonal form, even as severe gastroenteritis of infants and younger children, mostly in the first 2–3 years of life, with a peak at age 6–24 months [6]. National cause-specific mortality rates range from 439 per 100 000 (Sierra Leone) to less than 1 per 100 000 (50 countries) [6].

Gastroenteritis due to rotavirus is characterized by vomiting, fever and watery diarrhoea, and occasionally leads to severe dehydration and death in young children. Man is the only reservoir of infection, and transmission occurs by the faecal–oral route and can be attributed to poor standards of personal and environmental hygiene [7] in both developed as well as developing countries. Seasonal variation in the incidence of the disease has been noted, particularly in temperate climates where it peaks during the cooler months, while in tropical climates cases occur throughout the year [6].

Unfortunately, protective immunity against rotavirus infection is not completely understood, although serotype specific immunity is believed to play a major role [1]. The introduction of a rotavirus vaccine in some parts of the world makes it important to establish the impact of this organism in our population in Jordan to determine the need for vaccination. The study reported here from south Jordan is part of a national sentinel surveillance programme. The aims of study were to determine the incidence of rotavirus gastroenteritis among children aged under 5 years admitted with diarrhoea to Al Karak hospital and to map some of the clinical features associated with rotavirus disease (fever, severity of dehydration, vomiting and duration of illness).

Methods

A prospective hospital-based study was carried out over 1 year from 1 May 2007 to 30 April 2008. All cases of diarrhoea in children under 5 years old admitted to the department of paediatrics of Al-Karak general teaching hospital were recruited for the study. Patients were eligible if they were admitted for treatment of gastroenteritis and this was the primary illness; were aged ≤ 5 years; and had symptoms for 5 years; bloody diarrhoea; or symptoms ≥ 7 days duration. Patients with hospital-acquired gastroenteritis were also excluded.

Complete clinical examination was carried out and a questionnaire was filled for each child to collect data on demographic characteristics (e.g. age, sex) and clinical presentation (e.g. body temperature, vomiting, dehydration, duration of illness, date of admission). Fever was defined as body temperature ≥ 38 °C at the time of admission. Mild dehydration was diarrhoea and thirst; moderate and/or severe dehydration was depressed fontanel, sunken eyes, dry tongue and loss of skin turgor. The seasons of admission were recorded as: autumn (21/09–20/12); winter (21/12–20/03; spring (21/03–20/06); summer (21/06–20/09).

A stool sample was obtained from each child and analysed for rotavirus, using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (IDEIA rotavirus kit, DakoCytomation Ltd) and read with a photometer (Multiskan EX, Thermo Electron Corporation).

The data were analysed using SPSS, version 10. Data were presented as simple frequencies and percentages or means. The significance of differences between proportions or means were tested using the chi-squared or t-test respectively, with P < 0.05 as significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the whole group

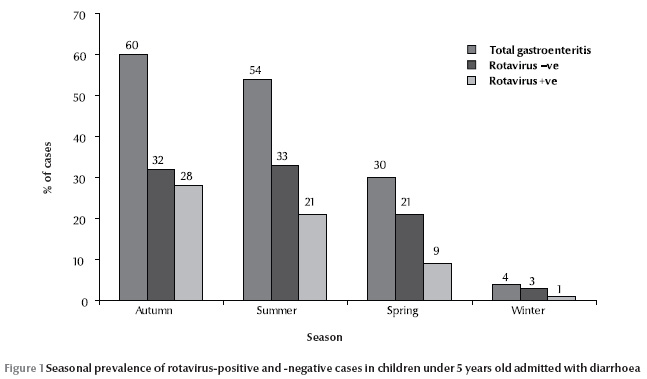

Data were collected for 148 children with diarrhoea, 87 males (58.8%) and 61 females (41.2%) (Table 1), a male to female ratio of 1.4:1. The age range was 0–60 months, with mean age 12.4 [standard deviation (SD) 11.5] months. The highest number of diarrhoea cases was during the autumn (60%) and the lowest in winter (4%) (Figure 1).

Out of 148 cases with diarrhoea 97 (65.5%) children presented with fever and 51 (34.5%) without fever. (Table 2) The mean age of children with fever was 13.8 (SD 13.0) months and without fever was 9.8 (SD 7.5) months.

A high rate of diarrhoea patients (107, 72.3%) presented with dehydration on admission; only 11 (7.4%) presented with severe dehydration, while the remaining 96 (64.9%) were considered to have mild dehydration. Patients with dehydration were significantly younger than those not presenting with dehydration [mean age 11.0 (SD 9.3) months versus 16.2 (SD 15.5) months] (t = 2.5, P = 0.013).

Demographic characteristics of children with rotavirus diarrhoea

We found 59 (39.9%) cases were ELISA-positive for rotavirus in their stool and 89 (60.1%) were ELISA-negative for rotavirus.

The great majority of cases of rotavirus diarrhoea (96.6%) were in children < 2 years old and 78.0% were among children aged < 1 year. A total of 39 cases (66.1%) were in males.

Children with rotavirus diarrhoea were significantly younger than children with diarrhoea caused by pathogens other than rotavirus [mean 8.8 (SD 6.3) months versus 14.8 (SD 13.4) months] (t = 3.205, P = 0.002). This inverse relationship between the age of children with diarrhoea and the incidence of rotavirus infection is shown on Table 1. The highest rate of rotavirus infection was found among patients aged ≤ 6 months (50.0%) and the lowest rate among those aged > 24 months (11.8%). In contrast, the highest rate of diarrhoea caused by pathogens other than rotavirus was among children aged ≥ 24 months (88.2%) and the lowest rate of non-rotavirus diarrhoea was in children aged ≤ 6 months (50.0%)(Table 1).

Rotavirus was detected at a higher rate in the stool samples of male (44.8%) than female patients (32.8%), a male to female ratio of cases of rotavirus infection of 1.95 to 1. However, there was no significant association between patient’s sex and rotavirus infection (χ2 = 2.14, P > 0.05)(Table 1).

Interestingly the seasonal pattern of diarrhoea, with a greater incidence in the autumn, was more pronounced among the children infected with rotavirus than those without. The highest incidence of rotavirus diarrhoea was during autumn (28%)(Figure 1).

Clinical characteristics of children with rotavirus diarrhoea

Out of the 59 rotavirus infection cases, 74.6% presented with fever, a significantly higher rate among children with diarrhoea due to rotavirus infection compared with the rate of fever (59.5%) in the 53 diarrhoea cases caused by pathogens other than rotavirus(Table 2). Fever occurred during rotavirus infection at a significantly younger age [8.8 (SD 6.3) months] than in diarrhoea cases caused by pathogens other than rotavirus infection [14.8 (SD 13.4) months] (t = 3.208, P < 0.05).

Severe dehydration was noticed in a slightly higher rate among patients with rotavirus infection, than diarrhoea cases caused by pathogens other than rotavirus (11.1% versus 9.6%); however this was not significant (Table 2).

The rate of vomiting was similar tin both groups (Table 2).

Outcomes

Most of the diarrhoea cases came for management during the first 7 days of illness with a mean duration of illness of 3.1 (SD 1.3) days. All the cases of diarrhoea were treated and cured within the first 15 hours with a mean of 3.1 (SD 2.3) hours. No deaths were recorded among either group.

Discussion

Diarrhoeal diseases remain a major cause of death in developing countries, especially in preschool children [1,7]. Children under 3 years of age may experience as many as 10 episodes of diarrhoea per year [7]. Rotavirus is among the most common causes of diarrhoea worldwide [7,8], accounting for 134 million episodes/year [7,9,10]. Although a vaccine has become available, rotavirus vaccine was not in use in Jordan at the time of the study.

Diarrhoeal disease is considered to be the most important cause of infant morbidity in Jordan [11]. Khuri-Bulos and Al-Katib in 2006 concluded that rotavirus was a significant cause of gastroenteritis in Jordanian children regardless of their social background [7]. In the present study the incidence of rotavirus diarrhoea among children in Al-Karak (39.9%) was slightly higher than in the north of Jordan (33%) as detected by Youssef et al. in 2000 [12]. This discrepancy can be attributed to differences between the populations, variations in the time of the study or to the laboratory tests used. We found a higher incidence higher than that detected in neighbouring countries: 24%, 37%, 35% and 37% in southern Iraq, northern Iraq, Islamic Republic of Iran and Turkey respectively [5,13–15]. The incidence was also considerably higher than 15% recorded in Spain [16]. In contrast, our rate was lower than the prevalence of rotavirus diarrhoea estimated in Saudi Arabia during 2004–05 (86%) [17] and in Turkey in 2005 (63%) [13]. It is also slightly lower than the prevalence of rotavirus diarrhoea in Kuwait (40%) [9]. This variation in the prevalence of rotavirus infection among different areas is probably due to the social habits of the population, e.g. personal hygiene, and/or environmental variations that may be related to growth of rotavirus pathogens particularly in contaminated water [7].

Although no significant association was detected between sex of patients and rotavirus infection in our study, the male to female ratio of cases with rotavirus infection was almost double (1.95:1), which is similar to another study in Jordan (1.85:1) [18], while a ratio of 1.5:1 was found in Bahrain [19]. The reason for this male predominance cannot easily be explained, although it may be due to social factors rather than a higher rate of infection in boys as parents in Arab societies may be more likely to take a male child to hospital than a female child. On the other hand a study in northern Iraq found no significant association between rotavirus infection and epidemiological characteristics, including sex [5].

The great majority of cases of rotavirus diarrhoea (96.6%) were in children < 2 years of age, and the mean age of rotavirus diarrhoea cases was significantly lower than diarrhoea cases caused by pathogens other than rotavirus (8.8 months versus 14.8 months). This age pattern is consistent with other studies from the region [9,12,13]. Children < 2 years may be more exposed to infection, or the older age group may have been exposed previously to rotavirus and acquired some immunity against infection [7]. Moreover, the mean age of children with rotavirus in our study [8.8 (SD 6.34 months] was lower than that found in northern Iraq [9.3 (SD 8.5) months] [5]. This early exposure of our children may be related to environmental factors such as water contamination [7]. We found an incidence of rotavirus among children aged < 1 year of 45.5% which is similar to the rates of 50% and 30% estimated in Kuwait [9] and Kurdistan respectively [5]. This difference could be related to breastfeeding and weaning times among populations in different areas or countries. There is evidence that breastfeeding has a protective role in rotavirus-associated diarrhoea [18].

We found that fever was significantly associated with rotavirus diarrhoea although we found no other studies with data on fever in rotavirus diarrhoea.

Our study demonstrated that the highest incidence of rotavirus diarrhoea was during autumn, followed by summer and spring, while the lowest incidence was during winter. This finding contrasts with other studies that found the highest incidence of rotavirus during winter in Islamic Republic of Iran, Pakistan, Oman and Tunisia (53%, 37%, 60.5% and 40.5% respectively [1]. Similarly in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia 50% of diarrhoea disease cases found during winter were caused by viruses, and 66% of these were due to rotavirus [20]. A 39.6% prevalence of rotavirus was found in northern Jordan during the summer (1992–93) [21]. In Spain 8% of rotavirus diarrhoea cases occurred during the winter months (January–March) [16]. The peak of rotavirus incidence in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Kuwait and Turkey was during winter [6,9,13]. In contrast to these studies, no seasonal variation was detected in Iraqi Kurdistan [5]. These differences may be due to environmental factors that may affect the survival rate of the rotavirus outside the body (temperature, humidity) and to contaminated water or its relation with level of chlorination of water, as rotavirus is inactivated only by chlorine, rather than other disinfectants [7].

Conclusions

This study in southern Jordan found rotavirus infection in 39.9% of children < 5 years old hospitalized with diarrhoea, predominantly in the age group < 2 years. There was a marginally higher rate of fever in the rotavirus cases than the non-rotavirus cases. The lowest rate of infection was in winter. No deaths were recorded among the rotavirus or non-rotavirus group.

Whether to introduce rotavirus vaccine to the national immunization schedule is now under discussion in technical health committees in Jordan.

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of a national sentinel surveillance that covered several sites in Jordan including our hospital. The surveillance system is financially and technically supported by VPI/DCD, WHO/EMRO. All the operating procedures, training of staff and supplies and equipment were provided by WHO/EMRO.

I am grateful to the Ministry of Health in Jordan, especially Dr K. Al Zain, to Dr S. Fa’ouri for his valuable review, to Dr N. Nawieshaa for statistical analysis and to Professor Dr W. Al-Kubaisy for her assistance.

References

- Teleb N. Update—EMRO surveillance network. Rotavirus Surveillance News, 2006, 1(3).

- WHO statistical information system (WHOSIS) [website] (http://www.who.int/whosis/en/, accessed 7 July 2010).

- Bahrdwaj A et al. Does rota virus infection cause persistent diarrhoea in childhood? Tropical Gastroenterology, 1996, 17(1):18–21.

- Zizdić S, Ridjanović Z, Masić. Novootkriveni serotipovi rotavirusa u cetverogodisnjem uzorku oboljele djece s dijarealnim sindromom [Newly discovered rotavirus serotypes in 4 years of collecting samples from children with diarrheal syndromes]. Medicinski Arhiv, 1992, 46(1,2):15–18.

- Ahmed HM et al. Molecular characterization of rotavirus gastroenteritis strains, Iraqi Kurdistan. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2006, 12(5):1420–1422.

- Estimated rotavirus deaths for children under 5 years of age: 2004, 527 000. World Health Organization [website] (http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/burden/rotavirus_estimates/en/index.html, accessed 7 July 2010).

- Khuri-Bulos N, Al Khatib M. Importance of rotavirus as a cause of gastroenteritis in Jordan: a hospital based study. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2006, 38(8):639–644.

- Communicable diseases: infections through the gastro-intestinal tract. Chapter 4. In: Gilles H, Lucas A, eds. Short textbook of public health medicine for the tropics, 4th ed. London, Hodder, 2003.

- Sethi SK et al Acute diarrhoea and rotavirus infections in young children in Kuwait. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, 1984, 4:117–121.

- Shukry S et al. Detection of enteropathogens in fatal and potentially fatal diarrhea in Cairo, Egypt. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 1986, 24:959–962.

- Annual report. Amman, Jordan Ministry of Health, 1989:97–99.

- Youssef M et al. Bacterial, viral and parasitic enteric pathogens associated with acute diarrhea in hospitalized children from northern Jordan. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology, 2000, 28:257–263.

- Özkana S et al. Water usage habits and the incidence of diarrhea in rural Ankara, Turkey. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2007, 101(11):1131–1135.

- Mohamood DA, Feachem RG. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of rotavirus and EPEC-associated hospitalized infantile diarrhea in Basrah, Iraq. Journal of Tropical Paediatrics, 1987, 33:319–325.

- Khalili B et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhoea in Iranian children. Journal of Medical Virology, 2004, 73:309–312.

- Gutiérrez-Gimeno MV et al. Nosocomial rotavirus gastroenteritis in Spain: a multicenter prospective study. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 2006, 25(5):455–457.

- Kheyami AH et al. Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea among children in Saudi Arabia: first detection of G9 and G12 strains. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2008 46(4):1185–1191.

- Faouri SG et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in children under three years of age in pediatric department at Al-Bashir hospital. Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, 1995, 95(4 Suppl.2/2):19–20.

- Dutta SR et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhoea in children under five years in Bahrain. International Journal of Epidemiology, 1990, 19(6):722–727.

- Meqdam MM, Thwiny IR. Prevalence of group a rotavirus, enteric adenovirus, norovirus and astrovirus infections among children with acute gastroenteritis in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 2007, 23(4):551–555.

- Meqdam MM et al. Viral gastroenteritis among young children in northern Jordan. Journal of Tropical Paediatrics, 1997, 43(6):349–352.