The Child and adolescent health in humanitarian settings: operational guide provides programmatic guidance to support the health care and protection of children during humanitarian emergencies. Itis a programmatic guide, not a clinical guide. Its focus is on equipping programme staff with the tools they need to confidently plan, implement, manage and evaluate child and adolescent health (CAH) activities in humanitarian emergencies, including preparedness, response and recovery.

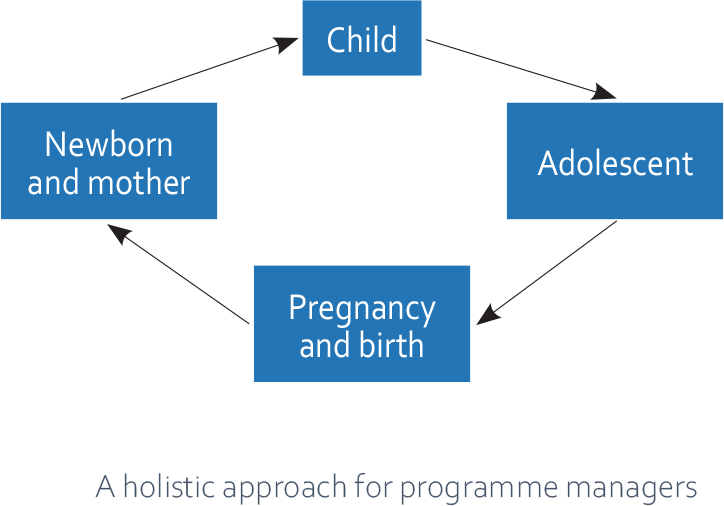

The operational guidecovers the full spectrum of child health from birth to adolescence (life-cycle approach) and all humanitarian emergencies, including natural disasters, armed conflict and political instability (all-hazards approach). Its primary purpose is to ensure that all children are fully included in humanitarian action.

The guideis a synthesis of existing standards and guidance material; it is not a new guideline or programme (Fig. 1). It presents these resources in a simple, systematic way, together with links to tools and other resources to support action.

Fig. 1 This operational guideis a synthesis of existing guidance information

The guidecomplements existing humanitarian frameworks (1), and child and adolescent health strategies (2), including the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) regional implementation framework (3). It is a companion to existing guides on newborn, and sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian emergencies (4–6).

Fig. 1 This operational guide is a synthesis of existing guidance information

Sections

Programme managers and health decision-makers in many related fields can have an enormous influence on child and adolescent health outcomes through well-informed decision-making.

The operational guide provides practical guidance for health managers and leaders who are involved in designing, implementing, managing, monitoring and evaluating child and adolescent health activities in humanitarian emergency settings. This includes staff in local and national governments, United Nations (UN) agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and academic and funding institutions.

While the guide's main target audience is programme managers and health decision-makers, it will also be relevant to staff in other sectors (e.g. social services), and especially to staff leading broader humanitarian/emergency and development activities. The guide will also be useful for local, national and regional advocacy on child and adolescent health in humanitarian emergency settings – including to support funding proposals.

The operational guide is designed to be practical, simple and action-oriented. It describes the essential programmatic actions necessary to protect and care for children and adolescents during humanitarian crises. All the actions depend on the local context and users must consider how to apply or adapt recommendations to fit local needs and circumstances.

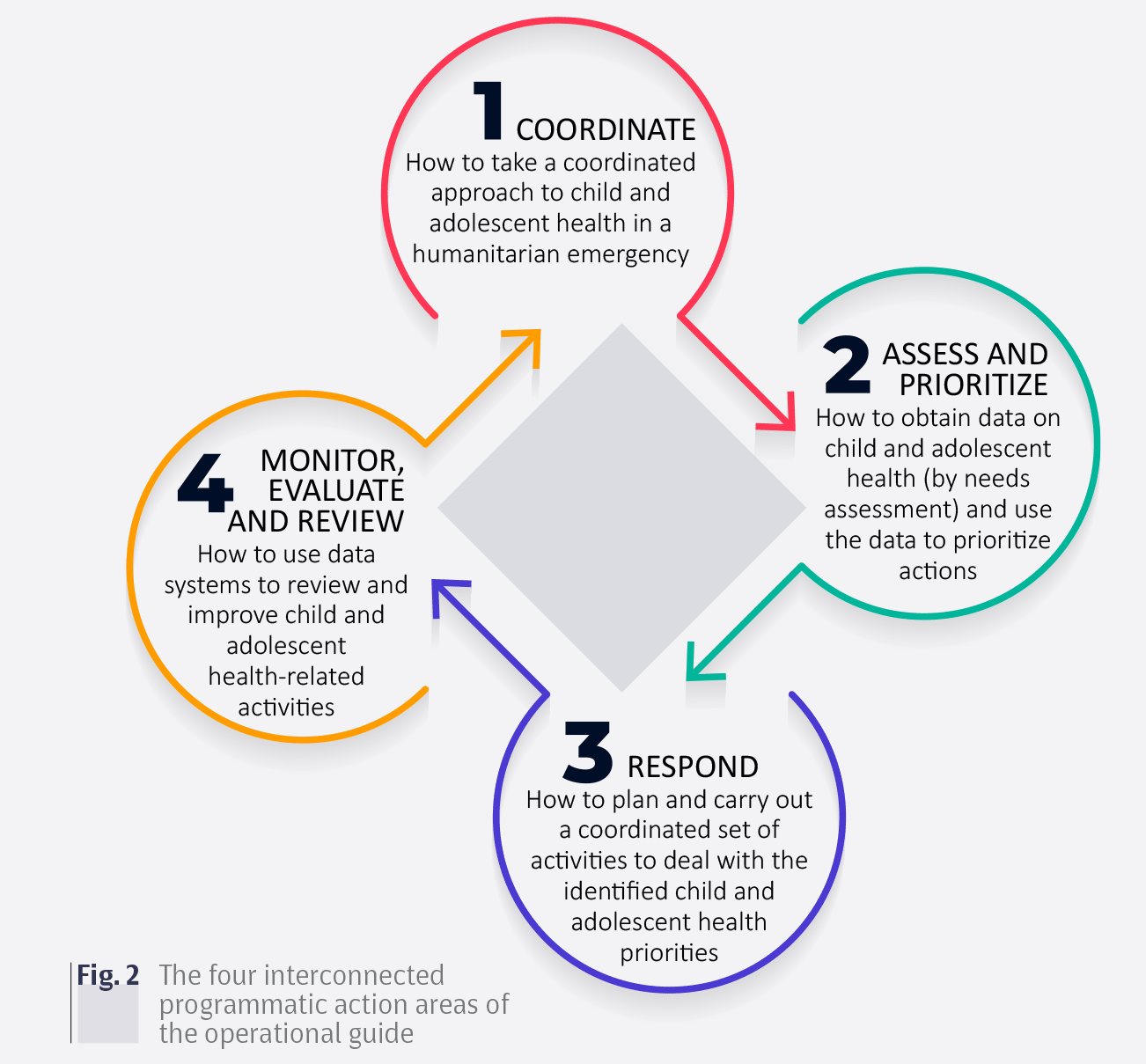

The guide is structured around four key programmatic actions: coordinate; assess and prioritize; respond; and monitor, evaluate and review (Fig. 2). These actions are part of a continuous cycle of activities. Each area of action is closely connected with other areas, and activities within each area will often occur at the same time.

Fig. 2 The four interconnected programmatic action areas of the operational guide

To familiarize yourself with the guide, start from the beginning and read through each of the four sections (action areas) in turn.

1. Coordinate – My team understands humanitarian structures, has a clear role within the health cluster and actively contributes to the child and adolescent (CAH) working group.

N.B.: A CAH working group meets across agencies and clusters to ensure minimum CAH standards and facilitate transition to comprehensive CAH standards for all programmes related to child and adolescent health. See section 1.3 for more details.

0 – not at all |

1 – partly true |

2 – mostly true |

3 – very true |

|---|---|---|---|

We don't really understand humanitarian structures or our role within the cluster system. |

We understand a little about clusters and humanitarian systems, but we do not really know where we fit in. |

We are somewhat involved in the health cluster, but not actively part of a CAH working group. |

We have a clear role within the health cluster and actively contribute to the CAH working group. |

2. Assess and prioritize – My team fully understands the situation of children and adolescents in our region, and has clearly prioritized specific focus areas for our context at this time.

0 – not at all |

1 – partly true |

2 – mostly true |

3 – very true |

|---|---|---|---|

We are not aware of the initial rapid assessment and are not up-to-date with situational reporting. |

We have seen some parts of the initial rapid assessment, but need more information before we can set priorities. |

We are aware of some assessments but have not worked with others to set priorities. |

We have assessed the situation (needs, resources, capacity), and have set priorities in collaboration with other stakeholders. |

3. Respond – My team understands the full range of CAH health activities, and actively works with other sectors to address the priority needs at this time.

0 – not at all |

1 – partly true |

2 – mostly true |

3 – very true |

|---|---|---|---|

We do not know what activities are important for children of different ages, or how to get these activities started. |

We are starting to think about what activities are important for children of different ages, and how to deliver them. |

We have some idea about what activities are important for children of different ages, and have started working on how to deliver them. |

We have considered the range of CAH activities and determined what needs to be done now, and how to do it. |

4. Monitor, evaluate and review – My team participates actively in health sector monitoring and evaluation activities, including supporting the CAH monitoring and evaluation plan and strengthening health information systems.

0 – not at all |

1 – partly true |

2 – mostly true |

3 – very true |

|---|---|---|---|

We are not aware of existing monitoring and evaluation plans and activities, and have little knowledge of health information or data systems. |

We are aware of some monitoring and evaluation activities, but we do not know where we fit in or what we should be doing. |

We understand and contribute to some monitoring and evaluation activities, but we do not have a clear role within the health sector's monitoring and evaluation plan. |

We understand and actively contribute to the health cluster's monitoring and evaluation plan and activities, and aim to strengthen existing data systems. |

Work out your focus

Start working through each section addressing the key actions to the best of your ability.

Don’t worry if there are some things that are impossible to address. Work on the things you can change. Build on what you are already doing well. Celebrate your small successes and encourage others. Make notes of areas you need to tackle more fully in the future.

Work through the action areas repeatedly

Work through the sections of the action areas of the operational guide repeatedly, each time trying to address more of the key actions.

The operational guide can be used during preparedness, response and recovery phases of humanitarian action. How you use the guide will depend on the emergency and context, but the following process is suggested.

- Work through the entire guide in preparation for an emergency.

- Quickly work through the guide in the first month of an emergency; then systematically revisit all the sections over the next 3–6 months.

- Systematically review all of the guide every 6 months during a protracted emergency and into the recovery period.

- Use the self-assessment progress tracker (Annex 1) to track your improvement.

Box 1 gives some more tips on using the operational guide.

Box 1 Getting the most from the operational guide

Here are a few tips to get the most out of the operational guide.

- Become familiar with the overall guide, but feel free to use the parts that are most relevant and useful to you. Don’t worry about doing everything.

- Adapt the guide to your context and people.

- Use the guide to orient new staff in your organization, and train and upskill existing staff – building understanding of their roles within the wider context.

- Use the guide when you are working with partners to help develop a common language and understanding.

- Consult the guide when developing your own strategies, standards and guidelines; you may find a lot of useful material to use or adapt.

- Use the guide as an advocacy tool to raise awareness and support for child and adolescent health in humanitarian settings.

- Use the guide as a quick reference to other tools and resources.

Limitations

The operational guidewill not solve all your challenges in coordinating, planning, delivering and evaluating CAH activities in humanitarian emergency settings.

In creating the operational guide, we recognize some limitations.

- The guide provides general, action-oriented guidance. It will always require some adaptation to be appropriate in your context.

- The guide relies on existing authoritative guidance documents. Sometimes, this guidance is incomplete or missing (e.g. adolescent health and other non-traditional areas for humanitarian health action).

- The guide focuses on broad actions and does not give detailed guidance. Sometimes, you will want to consult the source documents for more detail.

- The guide include selective information and resources. The omission of particular resources does not imply that they are not useful; we have simply aimed to prioritize resources.

Feedback on the guide

We encourage users to provide feedback on this working version of the Child and adolescent health in humanitarian settings: operational guide. Please complete the feedback form (Annex 8) as you use the guide, and email it to us: alraibyj@who.int; siddegk@who.int; hamish.graham@rch.org.au

Humanitarian emergencies are varied and complex. They immediately threaten the health and safety of children and young people, and can have long-lasting effects on their development and well-being. Every context is different, and emergency situations evolve rapidly. Humanitarian action must be flexible and responsive.

This section describes the general principles of and approaches to humanitarian emergencies and humanitarian action.

Terminology

Humanitarian emergencies may also be called humanitarian crises, complex emergencies and humanitarian disasters. They may simply be referred to as crises, emergencies or disasters. While each of these terms has a particular definition, in this document we use the following phrases interchangeably: humanitarian emergencies, emergencies and emergency settings.

Humanitarian emergencies

Humanitarian emergencies can arise from natural disasters (e.g. floods, earthquakes and famine), armed conflict, political instability and other social upheavals – often in combination (Box 2). Humanitarian emergencies commonly result in large-scale displacement of people, severe food shortages, and destruction of economic, political and social institutions. These events often make existing social and economic instability worse. Humanitarian emergencies cause high morbidity and mortality due to the direct effects of injury and illness and indirectly through disruption of health and social systems.

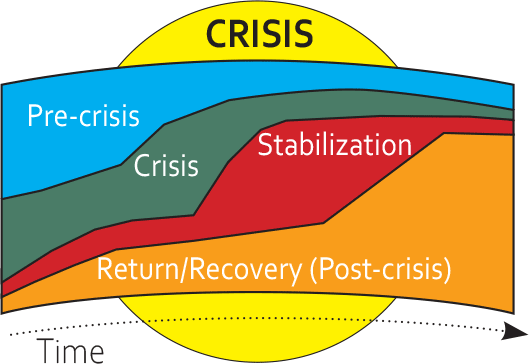

Humanitarian emergencies are traditionally described in four phases:

- Pre-crisis (before the emergency occurs);

- Crisis (when the emergency occurs and peaks);

- Stabilization (when immediate emergency concerns decrease);

- Recovery (after resolution of the emergency).

In most humanitarian emergencies, these phases overlap substantially (Fig. 3), especially in protracted emergencies. The operational guidewill be relevant for planning, implementing and monitoring activities during all phases; however your exact priorities and actions will vary.

Afghanistan. This protracted and complex crisis is an example of simultaneous rebuilding and emergency response requirements.

Iraq. The escalating conflict in Iraq has left 11 million people in need of assistance, with over 3 million people displaced, including 1.4 million children.

Lebanon. More than 1 million refugees from the Syrian Arab Republic now live in Lebanon, illustrating that humanitarian emergencies do not stop at borders.

Libya. Civil conflict and displacement from other countries (e.g. Syrian Arab Republic, Sudan) currently puts 1.5 million people in need of assistance, including many unaccompanied children.

Somalia. Drought, against a background of civil instability and conflict, has put Somalia on the brink of its third famine in 25 years.

Sudan. Conflict is decreasing, but more refugees from South Sudan are arriving, undernutrition is at a crisis point in Darfur and diarrhoeal outbreaks continue.

Syrian Arab Republic. The Syrian refugee crisis is the largest since the Second World War – 6 million internally displaced people, 5 million refugees in other countries, including more than 2 million children.

Yemen. Ongoing conflict and barriers to humanitarian assistance have resulted in a cholera outbreak and about 500 000 children with severe undernutrition.

Humanitarian emergencies are traditionally described in four phases:

- Pre-crisis (before the emergency occurs);

- Crisis (when the emergency occurs and peaks);

- Stabilization (when immediate emergency concerns decrease);

- Recovery (after resolution of the emergency).

Fig. 3 Humanitarian emergency phases (9)

In most humanitarian emergencies, these phases overlap substantially (Fig. 3), especially in protracted emergencies. The operational guide will be relevant for planning, implementing and monitoring activities during all phases; however your exact priorities and actions will vary.

Humanitarian action

Humanitarian action aims to save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity during and after crises. Humanitarian action takes place through all the phases of a crisis (pre-crisis, crisis, stabilization and recovery), and is also described in phases – preparedness, response and recovery (these often occur simultaneously).

- Preparedness requires government, humanitarian agencies, communities and individuals to have the knowledge and capacity, and the institutional relationships with others, to prepare for and be able to respond effectively to emergencies.

- Response involves immediate and longer-term relief efforts, including rapid assessment, strategic response planning, resource mobilization, implementation of response interventions and monitoring, and review and evaluation.

- Recovery (early and long-term) involves rebuilding and rehabilitation. Planning for recovery should start very early during the emergency with the goal of “building back better” (10).

The operational guide will be relevant for planning and implementing activities during all phases of humanitarian action, but your exact priorities and actions will vary.

Principles and standards

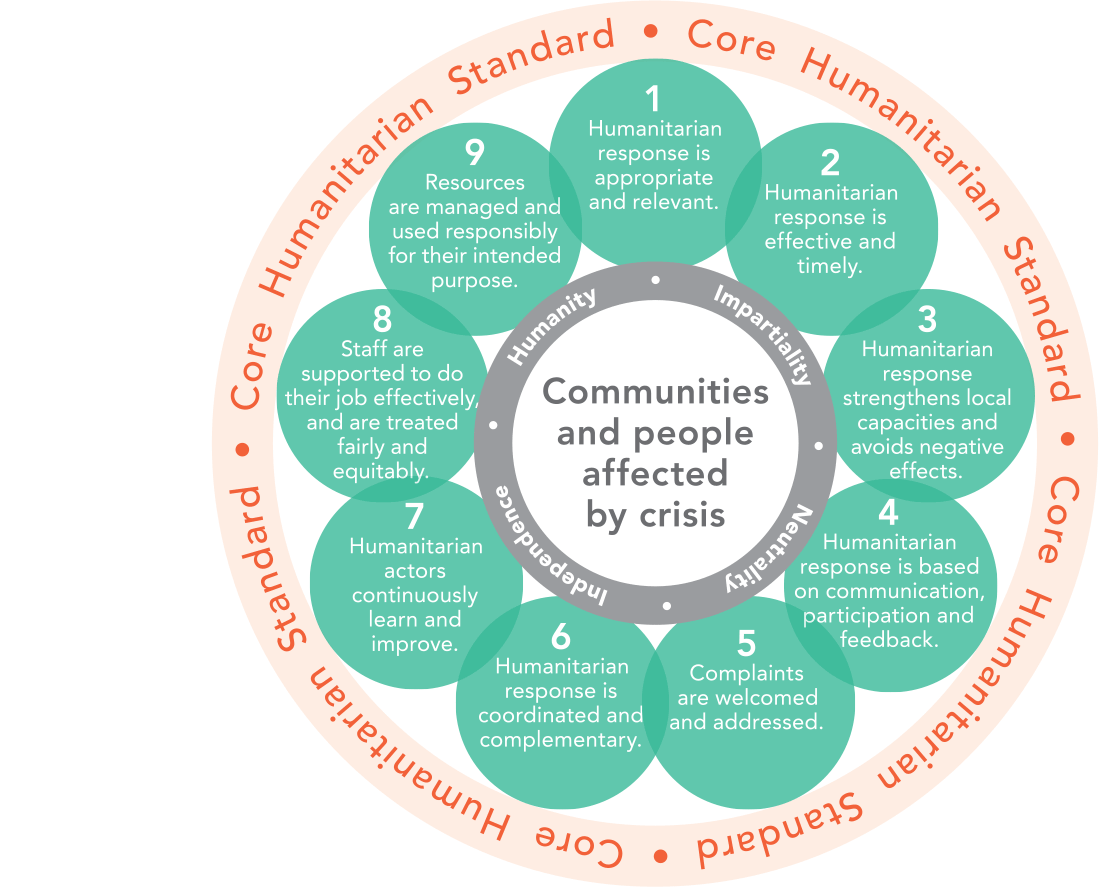

Humanitarian action is guided by the humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence. These are grounded in human rights and international law (11,12), specifically:

- the right to live with dignity

- the right to receive humanitarian assistance

- the right to protection and security.

Children have additional rights, described in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (13,14). The Core Humanitarian Standard is a consensus document from leading humanitarian actors (15). It is a voluntary code setting out nine principles to help humanitarian actors improve the quality and effectiveness of humanitarian action (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Core humanitarian standard (15)

The Sphere handbook: humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response (1) is the main humanitarian guidance document. It was created by a broad group of humanitarian actors and is accepted by most humanitarian agencies. The handbook includes the Humanitarian Charter, which outlines the ethical and legal foundations of humanitarian action, and the Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response. The Sphere standards have been adopted by the UN and other agencies (6). These standards are the main source for the key actions and indicators given in the operational guide.

Childhood is a period of enormous biological and social development – from birth to maturation (Fig. 5). The needs and capacities of a 4-year-old child will be very different from that of a 17-year-old adolescent, or a newborn baby.

To address child health in humanitarian emergencies adequately, we must understand the impact of humanitarian emergencies on children in each of these stages of development and the different responses needed. We must also understand that individual children mature at different rates, and sociocultural expectations and roles of children at different stages vary greatly in different contexts.

Fig. 5 Reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health continuum (16)

To capture the different needs and capacities of children as they grow, the operational guiderefers to children within five age groups:

- Newborns (neonates): first 28 days of life

- Young children: under 5 years

- Older children: 5–9 years

- Younger adolescents: 10–14 years

- Older adolescents: 15–19 years.

The operational guidecontains guidance that concerns all children, from newborns through to late adolescence, and other guidance that is more relevant to a particular age group. If guidance is directed to “children”, then it should be understood to apply to all children, including adolescents, infants and newborns.

It is important to note that the operational guideis limited by the availability of existing evidence and guidelines. Traditionally, most humanitarian emergency guidelines, interventions, research and policies have focused on young children. This means that there are many areas for which there is little evidence or guidance available – especially for older children and adolescents.

It is hoped that this operational guide will stimulate more attention to the needs of older children and adolescents in humanitarian emergencies, and that future editions of the guide will more fully address the needs of all age groups of children.

Child and adolescent health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region

Table 1 shows the leading causes of death and disability by age group in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Chronic conditions contribute substantially to morbidity and mortality (e.g. congenital anomalies, iron-deficiency anaemia, asthma and mental health conditions). Humanitarian emergencies have worsened the health and well-being of people of the Region, increasing the overall numbers of deaths from all causes, especially war-related violence.

Country-specific data can be found in the annual humanitarian needs overview for each country of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Action (UNOCHA) (17).

Table 1 Leading causes of death and disability in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region

Age group |

Leading causes of death (18) |

Leading causes of DALYs lost (19) |

Newborns |

1. Preterm complications |

1. Preterm complications |

Young child |

1. Lower respiratory infection |

1. Lower respiratory infection |

Older child |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

Older child |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

|

Younger adolescent (10–14 years) |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

1. Iron-deficiency anaemia |

Younger adolescent (10–14 years) |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

1. Iron-deficiency anaemia |

Older adolescent (15–19 years) |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

1. Iron-deficiency anaemia |

Older adolescent (15–19 years) |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

1. Collective violence and legal intervention |

DALY: disability-adjusted life year.

DALYs measure healthy years of life lost (i.e. death and disability).

Children and adolescents in humanitarian emergencies

Globally, one in four children (aged < 15 years) lives in countries affected by humanitarian emergencies – even more in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. For many children and adolescents, the shocks of the emergency come on top of existing challenges.

Many of these children are already vulnerable – living in poverty, deprived of adequate nutrition, out of school, at risk of exploitation. Such complex and protracted emergencies aggravate the risks these children face and exacerbate their needs. They also threaten their societies – potentially reversing hard-won development gains around the world.

Emergencies affect children and adolescents in many ways.

- Direct effects may include physical injuries and acute infectious disease from trauma and exposure to hazards, and psychological injury from exposure to trauma and abuse.

- Indirect effects may include physical and psychological injury and illness due to the breakdown of health services, food insecurity, separation from family members, homes and schools, and other forms of deprivation.

Children’s limited life experience can limit their ability to understand or deal with the challenges of emergencies. Children, particularly young children, are dependent on others for their basic needs and safety, and caregivers may neglect these needs in the face of more urgent demands.

Basic childhood activities, such as play, socializing with peers and learning, are often disrupted. Children and adolescents may take on additional responsibilities, for example, as breadwinners, or caregivers for younger children.

Some children and adolescents are particularly at risk of the harmful effects of emergencies (Box 3). Some people will experience emergencies differently to others (e.g. girls versus boys, urban children versus rural children).

For children and adolescents, emergencies threaten not only life and health, but also their physical, psychological, emotional and social development. Disruption to childhood development can have long-lasting effects.

However, children and adolescents are also uniquely resilient and adaptable with a remarkable capacity to survive and thrive. Supporting children’s and adolescents’ health and well-being during emergencies is a worthwhile investment for individuals, communities, and society.

Box 3 Child population groups at high risk

- Young children

- Girls

- Undocumented migrants, unaccompanied and separated children

- Children and adolescents from ethnic or religious minority populations

- Children and adolescents with disabilities or chronic health conditions

- Child and adolescent caregivers or primary income earners

- Children and adolescents in armed forces (and former combatants) or in the justice system

- Children and adolescents in forced or exploitative labour, including sex work

- Child and adolescent survivors of physical, sexual and emotional abuse

Resources

- Health Cluster guide: a practical guide for country-level implementation of the Health Cluster. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70128/WHO_HAC_MAN_2009.7_eng.pdf?sequence=1).

- Initiative. Compact for young people in humanitarian action [website]. Agenda for Humanity; 2016 (https://www.agendaforhumanity.org/initiatives/3829).

- Restoring humanity: synthesis of the consultation process for the World Humanitarian Summit [website]. World Humanitarian Summit Secretariat; 2015 (http://synthesisreport.worldhumanitariansummit.org/).

- UNICEF humanitarian action for children 2017 [website]. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2017 (https://www.unicef.org/hac2017/).

- Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to support country implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/framework-accelerated-action/en/).

- Health for the world’s adolescents. A second chance in the second decade. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 (https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/).

- ReliefWeb. Countries [website] (https://reliefweb.int/countries).

- One humanity: shared responsibility. Report of the Secretary-General for the World Humanitarian Summit. New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2016 (A/70/709) (http://sgreport.worldhumanitariansummit.org/).

- IHME. Eastern Mediterranean region Danger Ahead: the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990-2015.Int J Public Health. 2018. http://www.healthdata.org/emr

Tools

- The Sphere handbook: humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. Geneva: Sphere Association; 2018 (https://spherestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/Sphere-Handbook-2018-EN.pdf).

- Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability. Geneva: HAP International, People in Aid and the Sphere Project; 2014 (https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/language-versions). Available in 27 languages.