Research article

A.M. Mohamed,1 M.A. Ghanem 2 and A.A. Kassem 3

Correction

A.M. Mohamed, M.A. Ghanem, A.A. Kassem. Problems and perceived needs for medical ethics education of resident physicians in Alexandria teaching hospitals, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2012 Aug;18(8):827-35.

After publication, it came to EMHJ’s attention that the paper included text in the introduction and discussion from several sources to a high degree of similarity and without appropriate attribution or acknowledgement by the authors. The authors explained that this was inadvertently done and thus were requested to correct the relevant text in both sections. The revised paper is now available online, after careful review / acceptance by EMHJ.

المشكلات والاحتياجات المدركة لتعليم الأخلاقيات الطبية للأطباء المقيمين في المستشفيات التعليمية في الإسكندرية، مصر

عايدة محمد، مها غانم، أحمد قاسم

الخلاصـة: تدعو هذه الدراسة إلى المزيد من التأهب لمواجهة التحديات التي يصادفها الأطباء في واجباتهم المهنية المستقبلية. وتهدف هذه الدراسة المصرية إلى التعرُّف على المشكلات والاحتياجات لتعليم الأخلاقيات الطبية للأطباء المقيمين العاملين في المستشفيات الجامعية في الإسكندرية. وفي دراسة وصفية مستعرضة، أجاب 128 طبيباً مقيماً على استبيان ذاتي. كان رأي أكثر من نصفهم أن مقررات الأخلاقيات الطبية التي درسوها لم تَكُن فعّالة؛ وذكر %56.3 أن تخطيط المنهج كان سيئاً. واشتكى أغلبهم من أن تصميم المنهج لم يتواءم مع التخصصات، وكان المنهج قصير جداً، وهناك نقص في الموارد اللازمة لتيسير العملية التعليمية، وأن التقييم جرى حسب المعارف المكتسبة وليست المهارات. والمشاكل المتعلِّقة بالعاملين كانت قِلّة عدد العاملين مقارنةً بالطلاب، وعدم وجود خبرة لدى العاملين. وشعور المتدربون، بغضّ النظر عن النظام الإكلينيكي، بأنهم في حاجة إلى تطوير هائل في تعليم الأخلاقيات الطبية.

ABSTRACT There is a call for greater preparation for the ethical challenges encountered by physicians in their future professional duties. This study in Egypt aimed to reveal problems and perceived needs for medical ethics education of resident physicians working at University of Alexandria hospitals. In a descriptive, cross-sectional survey, 128 residents answered a self-administered questionnaire. More than half were of the opinion that their medical ethics course was ineffective; 56.3% mentioned poor curricular planning. The majority complained that the subject was not tailored to specialties, the course was too short, there was a shortage of resources to facilitate the educational process and that assessment was done for knowledge but not for skills. Problems related to staffing were low staff:student ratios and staff lack of experience. Trainees, regardless of clinical discipline, felt that there was a great need for improvement to their medical ethics education.

Problèmes et besoins perçus en matière de formation à l'éthique médicale des médecins internes des centres hospitaliers universitaires d'Alexandrie (Égypte)

RÉSUMÉ Certaines voix s'élèvent pour demander que les médecins soient mieux préparés aux difficultés éthiques qu'ils rencontreront dans leurs futures tâches professionnelles. Cette étude effectuée en Égypte auprès d'internes exerçant dans des hôpitaux de l'Université d'Alexandrie visait à révéler les problèmes posés par la formation à l'éthique médicale et les besoins perçus dans ce domaine. L'étude descriptive et transversale comprenait l'administration d'un autoquestionnaire auquel 128 internes ont répondu. Plus de la moitié d'entre eux estimaient que leur cours d'éthique médicale était inefficace, et ils étaient 56,3 % à mentionner une mauvaise planification pédagogique. Une majorité d'entre eux se plaignait de l'absence d'adaptation aux différentes spécialités, de la brièveté du cours, du manque de ressources permettant de faciliter l'apprentissage et reprochait à l'évaluation d'être centrée sur les connaissances et non sur les compétences. Les problèmes ayant trait au personnel était le faible ratio personnel/étudiant et son manque d'expérience. Quelle que soit leur discipline clinique, les internes interrogés pensaient qu'une amélioration de leur formation à l'éthique médicale était grandement nécessaire.

1Department of Community Medicine; 2Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology; 3Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt (Correspondence to A.M. Mohamed: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it )

Received: 27/03/11; accepted: 24/07/11

EMHJ, 2012, 18(8): 827-835

Introduction

Across graduate medical education, there is a call for more substantive preparation for the ethical challenges encountered by physicians during their residency training and in their future professional duties [1]. This has been viewed as necessary because of emerging evidence that medical residents face unique ethical conflicts that are related to their stage of training and also that their ethics training needs and preferences evolve over time [2]. Resident physicians in several studies have expressed a preference for clinically oriented ethics education to prepare them for the day-to-day ethical issues encountered in their work [3]. Data gathered over the past 3 decades also suggest that key differences exist in how men and women professionals approach health care ethics decision-making. Several studies indicate that women residents perceive a greater need for ethics preparation, value it more and see benefit in a more diverse set of educational methods than do men [4]. While ethics training has become a core component of medical residents’ education, curricula have been developed without consulting residents about their needs for ethics instruction. There have also been calls for new approaches in preparing residents for the ethical and professional issues they will encounter.

To our knowledge, there has been no systematic study in Egypt assessing the views of resident physicians on the need for ethics training, with a focus on practical issues. Moreover, little is known about the educational needs of practising physicians or their competencies in medical ethics in this country. The current study was predicated on the belief that understanding the perspectives of residents regarding ethics training will assist in efforts to create effective, valuable ethics education that, in turn, may foster the development of good physicians. It may highlight the importance of ethics education for residents directed at practical real-world dilemmas. Academic medicine may be better able to fulfil its responsibilities in teaching medical ethics and in serving its trainees by paying greater attention to these topics in graduate medical curricula. For this reason, a survey was conducted to reveal problems in medical ethics education from the point of view of residents in University of Alexandria hospitals and to explore their perceived needs for training about ethics.

Methods

Setting and sample

A descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted at the 3 university hospitals of Alexandria from August 2009 to September 2010. All physician residents of the faculty of medicine at University of Alexandria, working in 16 clinical departments, were invited to participate in this survey (n = 255, according to the hospital information system, 2008).

Data collection

An anonymous self-administered questionnaire was developed. It covered the demographic characteristics of residents (sex, occupational category and postgraduate year) and residents views about medical ethics education and perceived needs for training. These were presented as 24 statements related to problems in medical ethics education in 4 domains: planning (8 items), teaching (3 items) assessment (3 items) and staff (11 items). The items were scored as 1 (agree) and 0 (disagree). Residents were also requested to suggest methods by which any unsuccessful aspects of the training could be improved.

Official approval for implementation of the study was obtained from the director of the university hospitals. A pilot study was conducted on a random subset of residents (n = 30) prior starting the fieldwork in order to obtain information that would improve the research plan and facilitate the execution of the study and to test the data collection tools regarding the content, phrasing and order of items. The main obstacle encountered was the poor cooperation of residents in returning the questionnaire. This was due to high workload and shift work patterns. The response rate was 50.2% and did not differ significantly by department of affiliation.

The ethics committee of the faculty of medicine approved the study. Questionnaires were distributed by the investigator herself with a covering letter indicating the purpose of the study, confidentiality procedures and faculty review approval. Informed consent was taken from residents before starting data collection, after a full explanation of the purpose and aims of the study. Data about residents’ names, responses and views remained undisclosed by the researcher. After data analysis and final report writing all datasheets were shredded and disposed.

Data processing and analysis

After data collection, the raw data was coded and scored and a coding instruction manual was prepared. Data were fed to the computer and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 18.0. The significance of the results was judged at the 5% level of significance.

Results

Respondents’ characteristics

Of the 128 residents who responded to the questionnaire, 50.8% were males and 49.2% females. About one-quarter (24.2%) were working as internal medicine residents and 15.6% were specializing in family medicine; a minority were in the departments of paediatrics (6.3%) and psychiatry (3.1%). More than half of respondents (50.8%) were residents in other departments (dermatology, emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, surgery, radiology and anaesthesiology). Out of the total respondents, 13.2% were 1st year Masters students, 34.4% were 2nd year, 28.1% were 3rd year and only 24.2% were in the 4th year. No significant sex differences were observed among residents according to clinical department (P = 0.528) or postgraduate year (P = 0.724).

All residents received ethics education during their postgraduate years, most commonly in the 2nd year (34.4%). Less than half of residents (47.7%) were of the opinion that the courses were effective, while 52.3% believed they were ineffective.

Planning problems

Poor planning of curriculum

Of the residents who responded, 56.3% complained of poor planning of the curriculum. Significant sex differences were observed (P = 0.042), with more males (61.5%) than females (50.8%) agreed that poor planning was a problem (Table 1) . The majority of residents affiliated to family medicine (80.0%) and psychiatry (75.0%) stated poor planning compared with 62.5% of those attached to paediatrics and 35.5% of those in the internal medicine department (Table 2). Over half of residents (56.9%) attached to other departments mentioned poor planning. These differences were statistically significant (P = 0.007). The majority of 1st year residents (82.4%) believed poor curriculum planning was a problem compared with 54.5% of 2nd year residents, 50.5% of 3rd year residents and 51.6% of 4th year residents (P = 0.029) (Table 3).

Course not tailored to specialties

The majority of residents (85.2%) complained that the subject of medical ethics was taught in a generic way and was not tailored according to the particular needs of each specialty. No significant differences were observed by sex (P = 0.893), specialty (P = 0.495) or postgraduate year (P = 0.742) (Tables 1–3).

Poor timing of course

Less than three-quarters of residents (72.7%) felt that the timing of the course was inappropriate, i.e. was delivered either too late or too early within the schedule of the residency education programme. No significant differences were observed when sex (P = 0.782), department of affiliation (P = 0.059) or postgraduate year (P = 0.684) were considered (Tables 1–3).

Course too short

Just over three-quarters of residents (75.8%) felt that the course given was too short. No significant differences were observed when sex (P = 0.617) or department of affiliation (P = 0.051) were considered (Tables 1 and 2). The majority of 1st year (94.1%) and 2nd year residents (81.8%) commented about the shortness of the course compared with 69.4% of 3rd year and 64.5% of 4th year residents (P = 0.017) (Table 3).

Course too theoretical

More than three-quarters of residents (75.8%) felt that the course was too theoretical. Significantly more females (84.1%) than male residents (67.7%) stated this problem (P = 0.016) (Table 1). All residents affiliated to the psychiatry department stated this problem compared with 75.0% attached to paediatrics, 67.7% of residents specializing in internal medicine and 72.3% of those working in other departments. Residents specializing in family medicine were the least likely to mention this problem (45.0%) (P = 0.008) (Table 2).

Lack of teaching resources

The majority of residents (84.4%) stated that shortage of resources to facilitate the educational process (e.g. videos showing different ethical dilemmas problem). No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents by sex (P = 0.902), department of affiliation (P = 0.472) or postgraduate year (P = 0.294) (Tables 1–3).

Overcrowded teaching sessions

The majority of residents (89.8%) complained about the large number of postgraduate students. No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when sex (P = 0.836), department of affiliation (P = 0.603) or postgraduate year (P = 0.083) were considered (Tables 1–3).

Teaching methods

Over-reliance on lectures

The majority of residents (93.8%) criticized the dependence of staff on lectures as a mean of teaching. No significant differences were observed in responses of residents when sex (P = 0.845) or department of affiliation (P = 0.428) or year of graduation (P = 0.363) were considered (Tables 1–3).

Lack of practical sessions

The majority of residents (90.6%) stated that the teaching methods did not include applied practical sessions. No significant differences were observed by sex (P = 0.647) or department of affiliation (P = 0.492) or postgraduate year (P = 0.094) (Tables 1–3).

No teaching by simulation

The majority of residents (84.4%) stated that the teaching methods did not include role play or videos. No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when sex (P = 0.527), department of affiliation (P = 0.395) or postgraduate year (P = 0.584) were considered (Tables 1–3).

Assessment

Assessed knowledge only

The majority of residents (85.9%) stated that assessment was restricted only to knowledge gained rather than skills. This was stated by significantly more female residents (95.2%) than male residents (76.9%) (P = 0.017) (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when department of affiliation (P = 0.681) or postgraduate year (P = 0.503) were considered (Tables 2 and 3).

No assessment at clinical rounds

The majority of residents (91.4%) stated that no assessment was carried out during clinical rounds. No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when sex (P = 0.893), department of affiliation (P = 0.193) or postgraduate year (P = 0.062) were considered (Tables 1–3).

Absence of feedback

Almost three-quarters of residents (73.3%) complained that postgraduates did not receive any feedback about their performance as regards medical ethics after completion of courses in their departments. This was mentioned by significantly more female (92.1%) than male residents (63.1%) (P = 0.008) (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when department of affiliation (P = 0.738) or postgraduate year (P = 0.746) were considered (Table 2 and 3).

Staff

Staff to student ratio low

More than two-thirds of residents (67.2%) stated that the staff to student ratio was low. No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents according to their sex (P = 0.501) (Table 1). Significant differences were observed when department of affiliation was considered (P = 0.028). Significantly more family medicine (75.0%) and psychiatry department residents (75.0%) mentioned the low staff to student ratio as a problem compared with internal medicine (67.7%), paediatrics (50.0%) and residents attached to other departments (66.2%) (Table 2). No significant differences in the responses of residents were observed by year of graduation (P = 0.062) (Table 3).

Staff inexperienced in medical ethics

Another problem, according to 19.5% of residents, was that teaching staff lacked expertise in medical ethics. No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when sex (P = 0.197) or postgraduate year (P = 0.092) were considered (Tables 1 and 2). Significantly more residents affiliated to other departments (24.6%) and those specializing in family medicine (20.0%) were unsatisfied with the lack of expertise of staff in medical ethics compared with those attached to internal medicine (12.9%) or to psychiatry (12.5%) (P = 0.019) (Table 3).

Staff too busy

Three-fifths of residents (60.9%) stated that teaching staff were too busy. Significant sex differences were observed (P = 0.028) with more males (67.7%) than females (54.0%) believing it was a problem (Table 1). Three-quarters of residents attached to psychiatry (75.0%), 67.7% of those attached to internal medicine department and 66.2% of those attached to other departments stated that staff were too busy compared with 45.0% of those affiliated to family medicine and 25.0% of paediatrics departments. The differences observed were statistically significant (P = 0.001) (Table 2). Less than three-quarters of 3rd year residents (72.2%) found it a problem compared with 61.4% of 2nd year residents, 52.9% of 1st year residents and 51.6% of 4th year residents. The differences observed were statistically significant (P = 0.038) (Table 3).

Staff lack motivation

Less than two-thirds (62.5%) of residents stated that staff were not motivated and lacked the positive attitudes for teaching process. No significant differences were observed in the responses of residents when sex (P = 0.059) or postgraduate year (P = 0.138) were considered (Tables 1 and 2). Significant differences were observed when the department of affiliation was considered. (P = 0.002) (Table 2). Paediatrics (87.5) and internal medicine residents (77.4%) were more likely to state this compared with 55% who specialized in family medicine and those affiliated to other departments (55.4%).

Educational needs

Regardless of level of training or clinical discipline, residents felt that there was a great need for improvement in postgraduate education in medical ethics. Over three-quarters of residents felt that there was a need for faculty staff development through training (76.5%) and increasing the number of those who taught ethics (75.5%). The majority of residents (85.9%) recommended that the teaching of medical ethics should be fully integrated horizontally with the clinical courses and 78.9% of them felt that it should be linked to postgraduate education. Just less than two-thirds (64.8%) recommended that the subject should be taught throughout the medical education course.

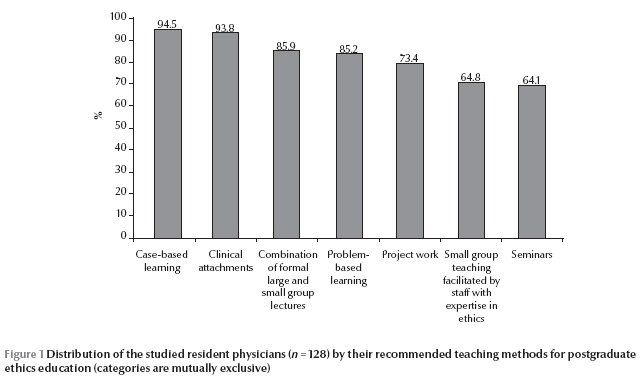

The majority of residents recommended that teaching of medical ethics should be more practical (92.2%), with proper selection of effective teaching methods (91.4%).Figure 1 illustrates the teaching methods recommended by respondents. Nearly all residents recommended case-based learning (94.5%) and clinical attachments in ethics education (93.8%). More than four-fifths (85.9%) recommended a combination of formal large and small group lectures or problem-based learning methods (85.2%). Other methods mentioned were project work (73.4%), small group teaching by expert staff (64.8%) and seminars (64.1%). Less than three-quarters of residents (71.9%) felt that assessment should be carried out by clinical staff in their departments.

Women expressed slightly greater need for attention to ethics education than did men (P < 0.05), with the greatest difference for the issues of teaching and assessment of medical ethics being fully integrated horizontally with the clinical courses and proper selection of effective teaching methods (data not shown).

Discussion

The importance of assessing medical ethics education has been established elsewhere [5,6]. The present study aimed to determine the resident’s views of the scope and content of required formal ethics components in the curriculum of University of Alexandria medical school. This survey has provided some information on the current situation of postgraduate medical ethics education at the faculty of medicine and provides some suggestions for improvement.

All the studied residents felt that there was a great need for improvement of the postgraduate medical education in ethics. The residents’ preference for integrating ethics throughout their medical education is particularly interesting. A diverse and continuing exposure to the moral dimensions of medical care seems to offer several benefits. First, it perpetuates the humanitarian tradition within medicine. Secondly, faculty staff can provide role models, especially at rounds, of the relevance and importance of moral practice to good medical care. Thirdly, courses and rounds together provide an opportunity for students to bridge ethical theory and moral decision-making in medical practice. Finally, it could assist students in defining their professional role, authority, responsibility and identity [7].

The present study addressed problems facing postgraduate medical ethics education at the University of Alexandria. Issues reported by the studied residents were related to problems of curriculum planning, teaching methods, staff and assessment methods.

As regards curriculum planning, more than half of the total residents surveyed (56.3%) complained of poor planning of the curriculum. A survey of medical ethics education at medical schools in the United States (US) and Canada in 2000 provides a useful comparison with this study [8]. Areas of similarity with our findings were inappropriate timing of the ethics component in the curriculum, overemphasis on theoretical elements and shortness of the course. Areas of difference were in poor planning of the curriculum and shortage of resources. However, that survey did not identify a lack of coordination between preclinical and clinical ethics training, perhaps as a result of the greater integration between these in the US and Canadian medical schools.

Concerning problems related to teaching methods, most residents of the present study criticized the dependence of staff on lectures as a mean of teaching. They also reported that teaching methods did not include any applied practical sessions. The residents recommended that teaching of medical ethics should be more practical and use effective teaching methods. Nearly all residents preferred case-based learning and attaching ethics education to clinical study. In agreement with Levitt et al. [9] the present study indicated that small group clinical-based teaching was widely accepted as the best approach for ethics teaching in this survey. There is now mounting evidence that small group teaching is an effective strategy for learning about medical ethics, being superior to lectures for developing moral reasoning skills [10] and normative identification with the future profession [11]. However, small group teaching usually requires more staff with the relevant expertise.

Several medical ethicists have introduced the concept of clinical medical ethics [12–15]. A clinical ethics teaching programme should emphasize the 5 Cs of teaching medical students: clinically based, real patient cases should serve as the teaching focus, continuous during the years of study, coordinated with the students’ other objectives, and clinicians should participate actively in the teaching effort both as instructors and as role models for the students. A more recent effective teaching method used in our faculty of medicine is the ethics case conference, from which the proceedings are published and made available to all health care professionals.

Concerning problems related to the staff, significantly more family medicine residents and psychiatry residents mentioned the low staff to student ratio as a problem. Other studies also reported a core group of ethics teachers within the medical school, with a very few individuals often responsible for ethics learning, the coordination of ethics teaching and much of the delivery itself [16–18]. Although a single identified person to take responsibility for ethics teaching in medical schools is desirable and recommended by the Pond Report [19], the fact that an individual is often so central to all activities within the ethics curriculum raises questions about succession planning. Several recommendations were provided by residents of the present study to improve staff problems in medical ethics education. A need for staff development through training and increasing the number of those who teach ethics were requested by the majority of residents.

As in a previous study [11], women residents in the present study perceived greater curricular needs for many items of ethics education than did male respondents. The reasons behind this gender effect are unclear and warrant further research. Because women represented 49.2% of all residents surveyed, and as many as 74% of residents in certain specialty areas, it will be important to determine the pattern of and reasons for the differential views of women and men residents related to ethics [20,21]. Women are an increasingly important stakeholder group in academic medical settings, and in the present study—as with others—they had greater unmet needs for ethics training [22,23]. Theoretical and empirical work has shown women placing a greater emphasis on relationships, values, compassion and an overall “ethics of care” in clinical ethics decision-making relative to men, who often express narrower rationales or more rule-based approaches [24].

As with other studies [25–28], the present study found that residents majoring in psychiatry, internal medicine, paediatrics and family medicine more strongly endorsed curricular needs related to ethical issues. Future work will continue to help clarify whether there are in fact different ethics education needs of residents in diverse fields of medicine.

The present study also revealed that a greater need for attention to ethics in the curriculum was perceived by senior residents at later stages of training. This may be because senior residents are more aware of their unmet needs for ethics training than the junior ones. Moreover, by the time they become senior residents physicians may face more complex clinical and ethical issues and need to deal with these effectively.

In conclusion, this survey, the first of its kind in University of Alexandria teaching hospitals, raises some important issues for ethics education. This study offers guidance for the inclusion of novel and important ethics domains in training curricula across medical school and diverse residency programmes. For example, faculty staff responsible for ethics education may wish to review their curricula systematically to ensure that certain topics have been included in their formal teaching programme. In addition, faculty may wish to make sure that topics receive particular emphasis in some specialty areas and to attend to the special interests of women trainees. To be valuable and effective, new approaches to ethics curricula must be responsive to the current complex ethical environment and attentive to the preferences of residents of both sexes, at different stages of training, with different patient care responsibilities.

Some limitations to the survey can be noted. It relied on self-reporting about problems of ethics education. It involved a sample at a single institution (only residents of teaching hospitals) and this limits the generalization of results to other settings. Also the fact that the response rate for the questionnaire was only 50.2% suggests there was a sampling bias. In addition, due to small the number of residents in certain specialties the study did not provide sufficient power to permit more detailed analyses. For example, it appears that psychiatry residents saw the greatest need for additional ethics education in relation to several specific topics and, possibly, overall, in comparison with their colleagues in other training areas. Whether this is an index of a higher ethical sensitivity, of greater perceived ethical complexity in mental health work, of lesser prominence of psychiatric ethics in training or other explanations is unknown but is worthy of further investigation.

References

- Four underserved/underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Rockville, Maryland, Cultural Competence Standards in Managed Care Mental Health Services, 2001.

- The changing medical profession: implications for medical education. World Summit on Medical Education, Edinburgh, 8–12 August 1993. Medical Education, 2003, 27(6):524–533.

- Kasman DL, Fryer-Edwards K, Braddock CH. Educating for professionalism: trainees’ emotional experiences on IM and pediatrics inpatient wards. Academic Medicine, 2003, 78:730–741.

- Hundert EM, Hafferty F, Christakis D. Characteristics of the informal curriculum and trainees ‘ ethical choices. Academic Medicine, 1996, 71:624–642.

- Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Lingard L. The disavowed curriculum: understanding student’s reasoning in professionally challenging situations. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2003, 18:1015–1022.

- Tomorrow’s doctors: recommendations on postgraduate medical education. London, General Medical Council, 1999.

- Dennis KJ, Hall MRP. The teaching of medical ethics at Southampton University Medical School. Journal of Medical Ethics, 1977, 3:183–185.

- Lehmann LS et al. A survey of medical ethics education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Academic Medicine, 2004, 79:682–689.

- Levitt C et al. Developing an ethics curriculum for a family practice residency. Academic Medicine, 1994, 69:907–914.

- Leach DC. The ACGME competencies: substance or form? Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 2001, 192:396–398.

- Roberts L et al. What and how psychiatry residents at ten training programs wish to learn ethics. Academic Psychiatry, 2000, 20:131–143.

- Siegler M. A legacy of Osler. Teaching clinical ethics at the bedside. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1978, 239:951–956.

- Pellegrino ED. ethics and moment of clinical truth. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1987, 239:960–961.

- Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine, 2nd ed. New York, Macmillan, 1986.

- Kass L R. Ethical dilemmas in the care of the ill: I. What is the physician’s service? II. What is the patient’s good? Journal of the American Medical Association, 1990; 244:1811–1806; 1846–1809.

- Diekema DS, Shugerman RP. An ethics curriculum for the pediatric residency program. Confronting barriers to implementation. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 1997, 151:609–614.

- Patenaude J, Niyonsenga T, Fafard D. Changes in the components of moral reasoning during students’ medical education: a pilot study. Medical Education, 2003, 37:822–829.

- Hayes RP et al. Changing attitudes about end-of-life decision making of medical students during third-year clinical clerkships. Psychosomatics, 1999, 40:205–211.

- The Pond report: report of a working party on the teaching of medical ethics. London, Institute of Medical Ethics, 1987.

- Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Xu G. Gender comparisons of young physicians’ perceptions of their medical education, professional life, and practice: a follow-up study of Jefferson Medical College graduates. Academic Medicine, 1995, 70:305–312.

- Wertz DC. Is there a “women’s ethic” in genetics: a 37-nation survey of providers. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association, 1997, 52:33–38.

- Crosdale M. More women than men seek entry to US medical schools. Washington DC, American Medial Association, 2004.

- Shrier DK. A celebration of women in US medicine. Lancet, 2004, 363:253.

- Sharpe VA. Justice and care: the implications of the Kohlberg-Gilligan debate for medical ethics. Theoretical Medicine, 1992, 13:295–318.

- Teaching medical ethics and law within medical education: a model for the UK core curriculum. Journal of Medical Ethics, 1998, 24:188–192.

- Coverdale JH et al. Are we teaching psychiatrists to be ethical? Academic Psychiatry, 1992, 16:199–205.

- Jacobson JA et al. Internal medicine residents’ preferences regarding medical ethics education. Academic Medicine, 1989, 64:760–764.

- Morenz B, Sales B. Complexity of ethical decision making in psychiatry. Ethics and Behavior, 1997, 7:1–14.