F. Sabih,1 K. M. Bile,1 W. Buehler,2 A. Hafeez,3 S. Nishtar4 and S. Siddiqi5

تنفيذ نظام صحي للمنطقة في إطار الرعاية الصحية الأولية في باكستان: هل يمكن للإصلاحات الجارية أن تعجِّل من وتيرة السير نحو المرامي الإنمائية للألفية؟

فرح صبيح، خليف بلّه محمود ، فيرنر بوهلر، أسد حفيظ، سانيه نيشتـر، سامين صديقي

الخلاصـة: تتزايد الثقة المتجدِّدة بالرعاية الصحية الأولية باعتبارها أفضل وسيلة لضمان جودة إيتاء الخدمات الصحية الرئيسية. ورغم أن لباكستان واحدة من شبكات النظم الصحية للمناطق الأكثر اتساعاً من حيث الانتشار، فإنه لم تقدِّم القدرات المتوقَّعة منها. بزغت سلسلة من جداول الأعمال لإصلاح النظام الصحي في الوقت الحاضر، ومنها ابتكار مضمومة أساسية من الخدمات الصحية. ورغم ذلك كله، فإن النجاحات في هذه الإصلاحات ستعتمد على قدرة الإطارات الثلاثة في الحكومة ولدى المعنيـِّين الآخرين على العمل معاً لتحسين الأداء بمجمله في النظام الصحي للمناطق. وتقدِّم هذه الورقة لمحة عن البنية التحتية للنظام الصحي للمنطقة، وتنظيم الخدمات في الرعاية الصحية الأولية في باكستان، والأنماط المتطورة للشوروية والأهمية الميدانية الأعمدة الرئيسية للنظام الصحي.

ABSTRACT There is growing renewed trust in primary health care as the best approach for ensuring equity in the delivery of essential health services. However, Pakistan with one of the most widely spread district health system networks in the region, has not delivered at the expected capacity. A series of health system reform agendas are now stipulated which include the promulgation of an essential health service package, public private partnerships and a people-centred focus. Nevertheless, success of these reforms will hinge on the ability of the three tiers of the government and other stakeholders to work together to improve the overall performance of the district health system. This paper provides an overview of the district health system infrastructure and organization of primary health care services in Pakistan, the evolving governance pattern and the operational significance and merit of health system pillars for effective service implementation.

Intégration du système de santé de district dans le cadre des soins de santé primaires au Pakistan : les réformes évolutives peuvent-elles accélérer la réalisation des objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement ?

RÉSUMÉ On observe une confiance renouvelée croissante dans les soins de santé primaires en tant que meilleure approche pour garantir l’équité dans la fourniture de services de soins de santé essentiels. Cependant, le Pakistan, dont le réseau de systèmes de santé de district est l’un des plus étendus de la région, n’a pas été en mesure d’assurer ces services au niveau attendu. Une série de calendriers de réformes du système de santé a maintenant été définie. Elle comprend notamment l’annonce d’un ensemble de services de soins de santé essentiels, des partenariats public/privé et une attention centrée sur l’individu. Mais le succès de ces réformes dépendra de la capacité de l’ensemble du gouvernement et des autres parties prenantes à travailler de concert pour améliorer les performances globales du système de santé de district. Cet article donne un aperçu des infrastructures de ce système et de l’organisation des services de soins de santé primaires au Pakistan, du mode de gouvernance évolutif et de l’importance opérationnelle des piliers du système de santé ainsi que de leur valeur pour l’intégration efficace des services.

1World Health Organization, Country Office, Islamabad, Pakistan (Correspondence to F. Sabih: ?

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

)

2Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Geneva

3National Health Services Academy, Ministry of Health, Islamabad, Pakistan

4Heartfile (health sector nongovernment organization), Islamabad, Pakistan

5World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt.

EMHJ, 2010, 16 (Supplement): S132-S144

Introduction

The district health system in the framework of primary health care is inextricably linked to the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 and has repeatedly regained international interest and renewed focus, exemplified in the Beijing Initiative and Qatar Declaration and the World health report 2008 [1–4]. After decades of focusing on vertical disease control programmes as prime drivers of health care development, a comprehensive approach to respond to the needs and legitimate health expectations of all citizens is back on the agenda. Effective community participation is the key for the successful implementation of PHC strategy; while the social determinants of health offer a dependable avenue for intersectoral collaboration.

The goal of “Health for All by the year 2000”, launched in 1977 through the World Health Assembly Resolution 30.43, was endorsed in Pakistan, by organizing delivery of health services through a fairly elaborate network of first-level care facilities, mainly basic health units and rural health centres, and the establishment of hospitals at each subdistrict level and district headquarter city [5]. Furthermore, in pursuance of the Alma Ata Declaration, successive national health policies of Pakistan since 1990 have reiterated their commitment to universal health coverage and affordable access to essential primary health care services [6]. At the grassroots level, the innovative concept of female community health workers led to the inception of the national programme for family planning and primary health care in 1994, commonly known as the Lady Health Workers Programme, linking the community with the district health system service delivery network [7].

There are 136 districts in Pakistan, and the district health system is a critical tier of the Pakistani health care system, since it functions as an independent administrative and organizational set-up for the delivery of service to the population. During 1999 to 2008, districts assumed even greater importance because of the devolution policy introduced by the previous government in 2001. This paper provides an overview of the district health system infrastructure and organization of primary health care services in Pakistan, the evolving governance pattern and the operational significance of health system pillars and their merit for effective service implementation and partnership.

Methods

Peer-reviewed articles on the framework of primary health care, primarily from Pakistan, were retrieved from scientific databases along with official documents of the government of Pakistan; grey literature was also reviewed. Field visits and interactions with key programme managers, primary health care staff and health policy-makers provided a valuable insight into the functioning of the district health system. Extensive use was also made of the district information system, which collects health information data from the district health network every month, to generate necessary evidence for analysis.

Delivery of health services: district health system infrastructure

The district health system in Pakistan is organized into a network of public service delivery outlets of Health Houses (community health outlets run by and set up in the homes of Lady Health Workers), a chain of first-level care facilities, and district and subdistrict hospitals. The district health system also incorporates a network of private providers ranging from general practitioners, clinics, hospitals and pharmacies to numerous alternative care providers including homeopaths and hakims for Eastern and Yunani medicine.

Table 1 shows the total number and types of health facilities including community outlets operated by the public sector and classified into the following categories:

Health Houses

The Lady Health Workers’ programme is arguably the largest public sector community health initiative in the region, covering most of the rural and selected peri-urban population of the country with a workforce of 100 000. The Health House, at the village level, constitutes the hub from where a Lady Health Worker carries out daily field visits to her catchment area population of 1000. The scope of the Lady Health Workers’ service covers health and nutrition promotion, maternal, neonatal and child health care including reproductive health and family planning, promotion of personal and environmental hygiene, treatment of minor ailments with options for referral and support to communicable disease control interventions. In 2009 LHWs’ direct involvement in vaccination was launched by training them in Routine EPI skills.

Basic health units

On an average, a basic health unit serves a population of around 10 000–25 000, providing a range of primary health care services (Table 2) along with referral support for major health problems. A basic health unit is usually staffed by a male medical officer, a Lady Health Visitor, a vaccinator, a health technician, a dispenser/dresser, a sanitary worker and other support staff.

Sub-health centres

These facilities are staffed with a physician, one Lady Health Visitor and a midwife and provide primary health care services to the catchment areas where there are no basic health units.

Rural health centres

Rural health centres function around the clock and serve a catchment area population of 50 000–100 000, providing a comprehensive range of primary health care services (Table 2). Rural health centres are equipped with laboratory and X-ray facilities and a 15–20 bed inpatient facility. The minimum rural health centre staff comprises a senior medical officer, woman medical officer, Lady Health Visitors, a midwife, a vaccinator, a health technician and a dispenser/dresser as well as laboratory, radiology, operation theatre and anaesthesia assistants along with administrative and support staff.

Civil dispensaries

These facilities were established in urban settings as part of the pre-independence health care delivery system, forming the bottom of the health pyramid. Two types of dispensaries are currently recognized: the municipal corporation civil dispensary, headed by a dispenser and the health department dispensary, operated by a physician.

Maternal and child health centres

These facilities provide maternal, neonatal and child health services including reproductive health and family planning; and are often located in urban and large rural areas. Maternal and child health centres are managed by Lady Health Visitors and assisted by a facility-based trained traditional birth attendant.

Tuberculosis centres

These centres detect and manage tuberculosis (TB) patients. The TB/DOTS Programme currently is also implemented by most first-level care facilities and hospitals of the district health system network.

Table 2 illustrates the primary health care services offered by basic health units and rural health centres to their respective catchment area communities, the basic health unit having an operational scope comparable to 30% of the services offered by a rural health centre. Despite this impressive network of first-level care facilities, their utilization rate by the catchment area population is low with less than one (0.6) patient visit/person/year.

Tehsil headquarter hospitals

These hospitals serve a catchment population of about 0.5–1 million, providing a range of preventive, clinical and rehabilitative services (Table 3). Presently the majority of tehsil headquarter hospitals offer 40–60 bed facilities and a range of outpatient services. There are 44 sanctioned posts including nine clinical specialists, of which at least an obstetrician and gynaecologist, a paediatrician and a general surgeon are almost always available.

District headquarter hospitals

These hospitals cover a catchment population of 1 to 3 million, with an average of 125–250 beds. The district headquarter hospital provides promotive, preventive, curative, advanced diagnostic and inpatient specialized services (Table 3). There are 74 sanctioned positions of which 15 are clinical specialties, although the level of actual deployment may vary between provinces.

Contribution of the Ministry of Population Welfare to the district health system

The Ministry of Population Welfare operates a network of around 3000 facilities for the delivery of reproductive health and family planning services ranging from reproductive health centres embedded in the tehsil headquarter hospital and district headquarter hospital service delivery domains and family welfare centres located at Union Council settings as well as mobile service units and community worker driven outreach services.

National priority programmes

The district health system hosts and supports the implementation of numerous federally funded national programmes, that include the Lady Health Workers’ programme; maternal, neonatal and child health; national AIDS control; Roll Back Malaria, national tuberculosis control; nutrition; prevention and control of blindness; control of hepatitis viral infections; and the expanded programme on immunization, closely interfacing with the primary health care services at district level. Many of these programmes have a dedicated workforce at district level with varying degrees of functional integration with the district health system; the federal and provincial management units of all these programmes providing the necessary technical and logistics back-up support for effective service delivery.

Health workforce

Diverse categories of health care providers serve in the district health system network facilities; which range from specialist physicians and surgeons to medical officers, nurses and midwives, Lady Health Visitors and different categories of paramedics along with administrative and support staff, with the Lady Health Visitors operating at the grassroots level. On average, 50 public sector health workers, including Lady Health Visitors, serve a 20 000 population catchment area. The performance of this workforce is critical for the provision of essential health services to the community. In addition to the human resource capacities at community, first-level care facility and hospital levels, the country has recently launched a large-scale training of community midwives operating at the grassroots level to enhance access to safe delivery and facilitate early referral, each covering a catchment area population of 5000–10 000. Although the national maternal, neonatal and child health programme has projected the training of 12 000 community midwives in five years, the current vision is to attain universal coverage through deployment of community midwives in all rural and urban underprivileged communities. Provincial and district health development centres have been established nationwide to act as resource training centres for capacity-building. However, these institutions have not received adequate support to operate effectively.

Health information

The national health information system covers all first-level care facilities and hospital outpatients of the district health system. Data collection forms are filled monthly by more than 110 districts. The facilities collect data on 18 priority health events, which along with malnutrition account for 65%–70% of the care-seeking load, including information on a package of primary care services, essential drugs, contraceptives, vaccines, supplies and equipment, and a range of institutional data that include health education sessions, home visits and achievements and recommendations; cumulatively covering 118 indicators.

Table 4 shows the common diseases and conditions diagnosed at different levels of the district health system network. In the past few years, efforts have been made to expand the scope of the health information system to incorporate information from hospital inpatients and the private sector. The enhanced health information system implementation has so far covered about 54 districts of the country. There is currently, however, no provision in either of the systems to collect and incorporate information from the tertiary care public hospitals and the private health sector.

Medical products and technologies

The public sector procurement functions of the district, including procurement of medicines, are managed by a special purchase committee. The process is governed through guidelines of the public sector procurement regulatory authority, an autonomous body with the responsibility of prescribing regulations and procedures and the monitoring of public sector procurements. At district level the procurement of the medicines has to conform to the national essential drug list that consists of 345 medicines, not restricted to generics, thus allowing the procurement of different branded items with higher price tags. Currently, of the over 60 000 entities registered under the Drugs Control Organization of the Ministry of Health, about 1300 are generics. The package of essential medicines procured for the first-level care facilities and hospitals include 30 and 37 broad categories of therapeutic drugs respectively. In principle, health facilities prescribe freely provided medicines, when available; however, most public sector facilities suffer from frequent stock-outs that force patients and families to procure drugs on their own.

Table 5 depicts the average number of days per month that essential drugs remained out of stock in various district health system outlets. On the other hand, procurement of medicines and other supplies, equipment and related technologies does not pursue nationally set technical guidelines. Likewise, there are no policies to replace used equipment after completing a defined depreciation period, making it difficult to sustain their functionality.

Health financing

Health financing in the public sector has long been suboptimal, with the allocated budgetary outlay for health constantly lagging below 1% of the GDP. The district health budget is released by the provincial government as part of a “one-line budget pool” allotted to 12 line departments of the district government, without any predefined preferential allocations to support efforts of the health sector to promote delivery of life-saving primary health care services. Moreover, a large proportion of the first-level care facilities’ budgetary outlay (80%) is allocated for salaries and operational costs, while the allowance for medicines does not exceed 6%. In tehsil headquarter hospitals and district headquarter hospitals, however, the share for the procurement of medicines and equipment may reach 20% of the budget of these institutions. Although the formal sector is covered by different forms of social health insurance, the informal sector has little or no social protection, making the risk of out-of-pocket catastrophic expenditures more likely to occur.

Table 5 illustrates the classification of the district health system budgetary allocations earmarked for different health facilities. The yearly unit costs of a basic health unit and a rural health centre vary between provinces, ranging from US$ 23 000 to US$ 65 000 (2005); with rural health centre allocations being 1.7 to 2.7 times higher than the budget allocated for basic health units, while the allocated cost per Lady Health Worker per year is US$ 675, including stipend, training, procured medicines and equipment and the expenditure incurred on monitoring and supervision.

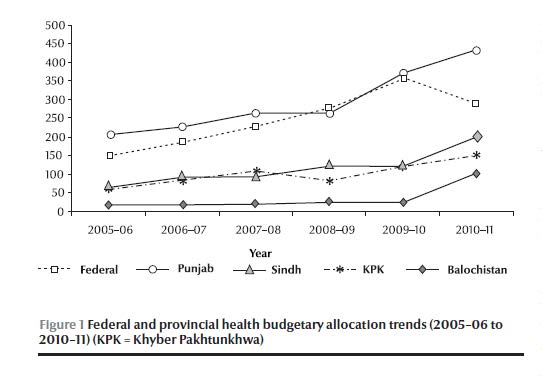

Figure 1 shows the trend in allocations from 2005–06 to 2010–11 at the federal and provincial levels. Federal health allocations increased over the years but decreased in 2010–11 due to the revised National Finance Commission award distribution, whereas provincial shares from the divisible pool were enhanced significantly. Provincial shares have increased from the present 47.5% to 56% in the first year of the National Finance Commission (2010–11) and to 57.5% in the remaining years of the award. However, provinces will have to work to make the targeting of these additional resources transparent and effective.

Organization and management

The primary health care services in a district are managed by an executive district officer overseeing the district health system network operations, while the district headquarter hospital is run by a medical superintendent. Both the medical superintendent and executive district officer report to the District Coordination Officer, provincial director-general for health services and the recently re-established divisional directors. The coordination between the executive district officer and medical superintendent is often weak and depends to a great extent on their efforts to generate partnerships and cooperation.

To improve the quality of service provision in rural settings, the federal and provincial governments opted to outsource a large number of basic health units on a nationwide basis to a nongovernmental organization, the People’s Primary Healthcare Initiative (PPHI), introducing substantive changes in the management of these facilities. The scheme was initailly launched in 2006 under the government’s new initiative sponsored by the Ministry of Industries and Special Initiatives and currently coordinated by the Cabinet Division of the Federal Government.

PPHI, a subsidiary of the provincial rural support programmes, in agreement with the federal and provincial government, negotiates contracts with the district authorities for management of basic health units and their service delivery. The provincial health departments transfer all the yearly budgeted funds for these facilities to PPHI, which are managed independently by federal, provincial and district PPHI support units.

Medical officers in the basic health units under PPHI are given contracts with a higher salary package and mobility incentives. Currently, the provision of basic curative care remains the main focus of PPHI-managed basic health units; with community support activities recently taken up through social organizers and support groups.

Community-based initiatives and social determinants of health

The implementation of community-based initiatives is led by the integrated and community centred Basic Development Needs approach, introduced in selected districts of Pakistan along with other Member States of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean Region, through WHO technical support. The Basic Development Needs approach has revitalized the fundamental principle of community organization, mobilization and participation in primary health care implementation, creating a direct connection between primary health care and social determinants of health and triggering health-centred integrated community action on water and sanitation, basic primary education, female literacy and participation and income generating livelihood activities leading to a significant improvement in maternal and child survival and nutrition health outcomes.

Discussion

Pakistan has a widely spread district health system network, where the hierarchically organized first-level care facilities and hospitals exceed 10 000, supported by a strong workforce of Lady Health Workers covering defined rural catchment area populations. However, this outstanding network has faced serious challenges to deliver at the expected capacity necessary for improving health outcomes and achieving the Millennium Development Goals. The most important impeding factor is an underperforming district health system unable to provide the necessary platform for implementation, forcing two-thirds of patients in urban areas and one-third in rural areas to seek care from formal or informal providers [8]. The low public health financing, unregulated private sector and the governance challenges are important factors undermining the service delivery capacity of the PHC system [9]. This is exacerbated by the weak primary health care services where interventions such as maternal, neonatal and child health including reproductive health and family planning, are progressing at a slow pace towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5, while Millennium Development Goal 6–related diseases continue to pose serious burdens, despite the universal implementation of numerous communicable disease control interventions in every district.

In the service delivery component, one of the constraints was the lack of an essential health service package matching the health needs of the population, comprising of core essential primary health care interventions of preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative services that are minimally required by the health system. Opportunely, the recent incorporation of an essential health service package in the 2010 national health policy with focus on maternal, neonatal and child health services could enhance coverage and access to essential primary health care services, with national disease control interventions becoming an integral component of the district health system [10,11]. This commitment, however, needs to be supported by appropriate resources and their effective use in order to ensure the desired impact.

The health workforce is another critical pillar of the district health system, for which the largest proportion of the health budget is allocated. Accordingly, it is imperative to develop a district health team perspective in order to address the community health agenda and engage in strategic planning to provide a coherent array of primary health care services. The government should expand the deployment of district health teams by enhancing the strength of Lady Health Workers, vaccinators and community midwives in all rural and urban slum settings, while in basic health units and rural health centres, the necessary female workforce should be guaranteed in order to improve social acceptability and access to the essential health service package [12]. Primary health care teams have to mobilize an active network of community participation in health promotion and disease prevention activities with provision of necessary emergency referral support. Furthermore, quality assurance in workforce performance needs to be sustained through continuing professional development along with hospital accreditation to deliver essential health services and improve patient safety.

These formidable human resource challenges need to be addressed at two stages; first at the pre-service level, establishing partnerships with undergraduate medical, nursing, midwifery and paramedical institutions and inculcating the concepts of community-oriented medical education, competence-based training and the skill mix and sharing principles of the district health team [13–15]. This will enable the would-be medical officers and other health workers in the primary health care network to become more attuned to the job at hand. The second stage relates to the service delivery level, where the concept of the district health team assumes greater significance, envisaging a needs-based human resource deployment, effective geographical distribution, capacity development, remuneration-based retention schemes and career development policies [16,17]. The collective accountability and image of the health team as the carer of the community, promoting health and preventing disease, in conformity with locally contextualized needs, should become a major district health system domain [18,19].

The district health system data pertaining to inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes of the primary health care system should be readily available and continuously updated. In practice, the district information system solely covers the public sector district health system outpatient data flow, while the information systems of national programmes, such as the Expanded Programme on Immunization and TB/DOTS, and the inpatient hospital data are reported separately in a fragmented manner. Another major limitation to be addressed constitutes the gap between the district information system and the decision-making process, where the practice of data generation, analysis and presentation is often delinked from the desired and indispensible evidence-based decision-making.

The insufficient availability of medicines has detrimentally affected the use of public health services in Pakistan, where a very limited proportion of public sector facilities had an uninterrupted flow of essential medicines [20,21]. To enhance access to life-saving primary health care services, essential medicines should be procured in sufficient quantities along with efforts to reduce stock-outs caused by improper procurement and transport, storage and management deficiencies. On the other hand, lack of standard procurement systems and effective use and maintenance of health technologies for the primary health care network, pose serious limitations to the delivery of quality care. The concept of health technology assessment may therefore be introduced to rationalize procurement, as this would enhance the essential health service package’s impact on prevailing health needs in a district.

A major challenge relates to health care financing, where the district health system struggles to obtain a fair share from the district’s one-line budget pool, distributed until recently by the district assemblies. Excluding the salary component, these funds are short of satisfying the minimum service delivery package necessary to support primary health care implementation, although the recent National Finance Commission Award distribution has enhanced provincial shares and created a larger fiscal space for the health sector. Moreover, the 18th constitutional amendment transferring larger budgetary outlay to the provinces should endorse the “managing for results” approach to enhance the pace towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals. The 2005–06 study of the national health accounts indicated that district governments are spending around half of the total provincial budgets [22]. However, health system strengthening demands greater allocation for health to at least 4% of GDP from the provincial share of the National Finance Commission Award to sustain the expected level of implementation.

Similarly, the health sector may further explore fairness opportunities through greater access to essential services and protection against unaffordable, out-of-pocket and catastrophic expenditure. Accordingly, there is a need to enhance the public sector budgetary outlay for health from its current level of less than 1% of the GDP leading to potential out-of-pocket expenditure, which is corroborated by a recent study estimating the public and private sector health expenditure at 2.9% of the GDP [23]. However, through appropriate linkages with ongoing expansion of social safety arrangements in Benazir Income Support Program the base of PHC financing and mandatory essential services’ utilization can be broadened [24].

In Pakistan, similar to many other developing countries, the district health system has been facing a range of governance challenges impeding the organization, implementation and management of essential health services; poorly supported by weak strategic and operational planning, irregular monitoring and supervision, an inadequate accountability system and insufficient community participation and intersectoral action [10,25–27]. The Pakistan Devolution Plan under the Local Government Ordinance 2001 aimed to make the districts answerable to the elected chief executive of the district (District Nazim) for better governance and improved service delivery. Analysis of the district devolution impact on the governance of district health system gave mixed results, as shifting power without transferring knowledge and skills proved counterproductive [28]. Even though the responsibilities of the district health teams have increased, non-provision of adequate management training, lack of managerial flexibility and the high turnover of executive district officers has constrained implementation.

The managerial outsourcing of a large number of basic health units to PPHI was intended to improve the performance and outcomes of this critical level of the district health system. PPHI has shown an immediate enhancement of attendance and use of basic health units which could be attributed to improvement in availability of medicines and waiver of user charges. PPHI is addressing the previous weakness in its model, with curative services being the exclusive focus, and is now working towards making its BHU hubs for delivery of comprehensive primary health care services to the community [29,30]. In future, in order to improve the coordination and quality of outsourcing, transparent and merits-based contractual bidding and selection procedures must be designed, while the interface between the contractual partner and the district health team must allow for a formal performance oversight, accountability, greater community participation and intersectoral action [29].

On the other hand, provincial governments when recruiting members of the district health team should be cognizant of the necessity to engage the right technical and managerial merit-based capacities and address the current rapid turnover of senior managers, which negatively affects the district health system’s operational sustainability. Special efforts need to be made to forcefully pursue the jointly promulgated memorandum of understanding for better coordination and functional integration of reproductive health and family planning services provided by the ministries of health and population welfare, especially at the grassroots level [31,32]. In their monitoring capacities, the federal and provincial governments may jointly organize nationwide quality assessment and impact monitoring to enhance accountability and focus on results.

Concurrently, district health promotion network action should be established to reach out to local communities, households, schools, working places and market settings. Integration of emergency preparedness and response interventions into the district health system’s operational plans is also required in order to mitigate avoidable morbidities and mortalities evolving during disasters. A well performing district health system would also strongly benefit from national and provincial efforts to regulate key public health policy dimensions that cannot be executed independently at the district level. These include the promulgation and implementation of public health legislation against the hazards of tobacco consumption; food fortification and safety; safe blood transfusion; safe drinking-water and sanitation; solid waste disposal; road traffic safety; regulation of the private sector; patient safety; and enhancing public private partnerships while promoting health in public policies.

In conclusion, primary health care still remains the most rational way for achieving Health for All and the Millennium Development Goals, while the district health system provides an ideal platform for its implementation [19,33]. Health system strengthening in the framework of primary health care will require effective deployment of coordinated strategies to ensure the provision of essential services, medicines and technologies, the deployment of a qualified and accountable health workforce, use of evidence in decision-making and the allocation of predictable budgetary outlay supported by an effective and transparent stewardship at all operational levels. To attain significant progress towards the Millennium Development Goals, the three tiers of the government (district, provincial and federal) have to work together for better coordination and strategic unity, while forging purposeful alliances with civil society organizations, other relevant public sector line departments and international development partners.

References

- Declaration of Alma Ata. International conference on primary health care. Alma Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978 (http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf, accessed 13 July 2010).

- Development of rural primary health care. Beijing initiative for responding to challenges by giving priority to health. International conference on the development of rural primary health care. Beijing, China, 1–2 November 2007 (http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/10BB01FA-A891-49FA-9119-14BAFB3CD056/0/file.doc&ei=L4U8TMayGNy4jAfM39GZAQ&usg=AFQjCNGpobEtl6Q2eccaddVFMLO3g4OTHA, accessed 13 July 2010).

- Qatar declaration: health and well being through health systems based on primary health care. International conference. Doha, Qatar, 1–4 November, 2008 (?ttp://gis.emro.who.int/healthsystemobservatory/researchandpublications/Documents/Qatar%20PHC%20Conference.pdf, accessed 13 July 2010).

- World health report 2008–primary health care: now more than ever before. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2008.

- Seventh five-year development plan 1988–1993. Islamabad, Pakistan, Planning Division, 1988.

- National health policy 1990. Islamabad, Pakistan, Ministry of Health, 1990.

- National health policy 1997. Islamabad Pakistan, Ministry of Health, 1997.

- Karim MS. Disease pattern, health services utilization and cost of treatment in Pakistan. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 1993, 43:159–164.

- Nishtar S. Mixed Health Systems Syndrome. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2010, 88:74–75 (doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.067868).

- Hansen PM et al. Determinants of primary care service quality in Afghanistan. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 2008, 20(6):378–383.

- Ghaffar A, Kazi BM, Salman M. Health care systems in transition 3. Pakistan, part 1: an overview of the health care system in Pakistan. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 2000, 22(1):38–42.

- Mumtaz Z et al. Gender based barriers to primary health care provision in Pakistan: the experience of female providers. Health Policy and Planning, 2003, 18(3):261–269.

- Aziz A et al. Knowledge and skills in community oriented medical education (COME) Self-ratings of medical undergraduates in Karachi. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 2006, 56(7):313–317.

- Farid-ul-Hasnain S, Israr SM, Jessani S. Assessing the effects of training on knowledge and skills of health personnel: a case study from the family health project in Sindh, Pakistan. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 2005, 17(4):26–30.

- Begum S, Aziz-un-Nisa, Begum I. Analysis of maternal mortality in a tertiary care hospital to determine causes and preventable factors. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 2003, 15(2):49–52.

- Kampala declaration on fair and sustainable health financing. Kampala, Uganda, WHO Country Office World Health Organization, 2005 (https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/kampala.pdf, accessed 13 July 2010).

- Serneels P et al. Who wants to work in rural health post? The role of intrinsic motivation, rural background and faith based institutions in Ethiopia and Rwanda. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2010; 88: 342–349.

- Mahmood MA, Moss J, Karmaliani R. Community context of health system development: implications for health sector reform in Pakistan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2003, 9(3):464–471.

- Siddiqi S et al. Primary health care, health policies and planning: lessons for the future. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2008, 14:S42–S56.

- Masud TI, Farooq N, Abdul Ghaffar. Equity shortfalls and failure of the welfare state: community willingness to pay for health care at government facilities in Jhelum (Pakistan). Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 2003, 15(4):43–49.

- Pakistan: Medicine price, availability, affordability and price components. Cairo, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2008 (WHO-EM/EDB/095/E).

- National health accounts Pakistan 2005–2006.Islamabad, Pakistan, Statistic Division, Federal Bureau of Statistics, 2005.

- Nishtar S. Health financing. In. Choked pipes: reforming Pakistan’s mixed health system. Karachi, Pakistan, Oxford University Press, 2010:77–106.

- Thailand: health care for all, at a price. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2010, 88:84–85.

- Siddiqi.S et al. Framework for assessing governance of the health system in developing counties: gateway to good governance. Health Policy, 2009, 90(1):13–25.

- Tarin E et al. Policy process for health sector reforms: a case study of Punjab Province (Pakistan). International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 2009, 24(4):306–325.

- Shaikh BT et al. Contracting of health care services in Pakistan: is up-scaling a pragmatic thinking? Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 2010, 60(5):387–389.

- Devolution in Pakistan: overview of the ADB/DFID/World Bank study. Islamabad, Asian Development Bank, DFID, World Bank, Pakistan, 2004.

- Siddiqi S, Masud TI, Sabri B. Contracting but not without caution: experience with outsourcing of health services in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean region. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2006, 84(11):867–875.

- Sheikh B T, Hatcher J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. Journal of Public Health, 2004, 27(1):49–54.

- Bile K. The imperative of functional integration for achievement of MDGs. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 2009, 50(9):S34–8.

- Douthwaite M, Ward P. Increasing contraceptive use in rural Pakistan: an evaluation of the Lady Health Worker programme. Health Policy and Planning, 2005, 20(2):117–123.

- Abdullatif AA. Aspiring to build health services and systems led by primary health care in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2008, 14:S23–S41.