Review

S.A. Murray 1 and H. Osman 2

الرعاية الملطِّفة الأولية: قدرات أطباء الرعاية الأولية باعتبارهم مقدمين للرعاية الملطِّفة في المجتمع في إقليم شرق المتوسط

سكوت موري، هبة العثمان

الخلاصة: تركز الرعاية الملطِّفة على تحسين جودة الحياة وتخفيف معاناة المصابين بأمراض مزمنة متفاقمة. ولاتزال خدمات الرعاية الملطِّفة محدودة في إقليم شرق المتوسط على الرغم من الحاجة الماسَّة والمتزايدة إليها. وقد عدَّت منظمة الصحة العالمية تطوير الرعاية الملطِّفة أولَويَّةً من الأولويات الإقليمية. وتلقي هذه المراجعة الضوء على الحاجة الملحّة لتقديم هذه الرعاية في الإقليم، وترى أنَّ تمكين مقدّمي الرعاية الأولية في الإقليم هم من أفضل من يقوم بإيتاء الرعاية الملطِّفة في مجتمعاتهم، ولما كان الطب التلطيفي لم يعتبر بعد واحداً من الاختصاصات الأساسية في الإقليم، فإن التدريب والدعم في الرعاية الملطِّفة مطلوبان لبناء القدرات في الرعاية في نهاية الحياة، وإتاحة هذا الأسلوب للمرضى الذين سيستفيدون منه على أسس عادلة، وفي أبكر وقت ممكن.

ABSTRACT Palliative care focuses on improving the quality of life and relieving suffering in patients with progressive chronic illnesses. Palliative care services remain very limited in the Eastern Mediterranean region although the need for them is high and increasing. The World Health Organization has identified the development of palliative care as a regional priority. This review highlights the urgent need to provide such care in the region and proposes that primary care providers in the region are well placed to provide palliative care in their communities. As palliative medicine is not established as a specialty in the region, training and support in palliative care are required to build capacity in end-of-life care and to allow all patients who would benefit from this approach access to it equitably and early in their illness.

Soins palliatifs en soins de santé primaires : potentiel des médecins des soins de santé primaires en tant que fournisseurs de soins palliatifs en communauté dans la Région de la Méditerranée orientale

RÉSUMÉ Les soins palliatifs sont polarisés sur l’amélioration de la qualité de vie et sur l’allégement des souffrances des patients atteints de maladies chroniques évolutives. Les services de soins palliatifs restent limités dans la Région de la Méditerranée orientale malgré un besoin élevé et croissant en la matière. L’Organisation mondiale de la Santé a identifié le développement des soins palliatifs en tant que priorité régionale. La présente analyse souligne l’urgente nécessité de fournir de tels soins dans la Région et suggère que les prestataires des soins de santé primaires régionaux, bien placés dans leur communauté, fournissent ces soins palliatifs. La médecine palliative n’étant pas établie en tant que spécialité dans la Région, une formation et un appui en soins palliatifs sont requis pour renforcer les capacités en soins de fin de vie et permettre à tous les patients qui pourraient tirer avantage de cette approche d’y avoir accès de manière équitable dès le début leur maladie.

1Primary Palliative Care Research Group, Centre for Population Health Sciences, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom.

2Department of Health Promotion and Community Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon (Correspondence to H. Osman: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it )

EMHJ, 2012, 18 (2): 178-183

What is palliative care?

Palliative care focuses on relief of suffering and improvement of the quality of life and in due course death in patients with progressive life-threatening illness [1]. Although control of physical symptoms is an important aspect of palliative care, there is also a strong focus on the psychological, social and spiritual dimensions of the illness experience, and an emphasis in planning to consider the future care the patient wants and also possibly aspects that the patient may not wish to receive. Ideally, palliative care should be initiated soon after a patient is diagnosed with a life-threatening progressive illness and be increasingly delivered in parallel with disease-modifying care [2]. Palliative care is also important in the last days of life [3]. Hospice usually refers to palliative care at the end of life when curative or disease-modifying care is no longer an option. Hospice can refer to a location of care, a health insurance benefit, or a philosophy of care.

Why is palliative care needed?

Provision of palliative care has been shown to improve quality of life and reduce depression in patients with life-threatening illness [4]. A recent study in the United States of America (USA) in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer also showed that early referral to palliative care significantly improved survival [4]. Caregivers of patients who receive palliative care may have an easier bereavement period and be less likely to suffer depression after the death of their loved one. Given the increasing burden of chronic illness and the fact that cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage in the Eastern Mediterranean (EM) region, the need for palliative care is very high [5].

Current situation in the Eastern Mediterranean

Unfortunately, palliative care services in the EM region are limited and the number of physicians trained in palliative care in the region is well below the needs of the population [5]. Similarly the training of family physicians in this approach is under-developed. Traditionally, medicine has trained physicians to diagnose and treat diseases. Few physicians are trained in providing the palliative care approach that patients with chronic progressive illnesses need, and in planning for and conducting a good death for their patient.

Once a disease progresses and as the needs of patients change towards the end of life, physicians often feel that they lack the skills needed to support their patients. Patients and their caregivers can feel confused and unsupported. Patients with terminal illness report fear of pain and suffering that may be associated with their disease [6]. They may also feel abandoned by their physicians towards the end of life [7]. The needs of patients can be addressed more appropriately and effectively if the focus of medical management shifts from curative to supportive care and palliation once a physician feels that they would not be surprised if their patient died within the next 12 months [8].

Since the early 1990s there have been a few initiatives towards the development of palliative care in the EM region. In Lebanon, efforts to integrate palliative care into medical and nursing curricula and to train clinicians in palliative care started in the 1990s [9]. Although provision of palliative care services has remained very limited, the Ministry of Public Health recently demonstrated a strong commitment to the development of a national strategy for the development of palliative care by launching a National Committee on Palliative Care in May 2011. Palliative care programmes in Jordan have been growing with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO) and Jordan Ministry of Health [10]. One of the most developed palliative care programmes in the region is the hospital-based palliative care unit at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center in Saudi Arabia. This unit has been proposed as a regional training centre for physician leaders in palliative care [11].

The way forward: taking palliative care forward in the community

There is an urgent need to develop palliative care services in the EM region to be able to provide the compassionate person-centred type of care that patients with life-threatening illness need, care that respects their values and religious beliefs. WHO has set the development of palliative care as a regional priority [5]. Building palliative care services into existent primary care systems and hospital settings has been proposed as an approach to build capacity in palliative care in all settings [2]. Primary care systems are ideally placed to address the 4 key challenges that face palliative and end-of-life care in the next 10 years in that they can:

care for people with all life-threatening illnesses

identify and treat patients early in the course of the illness

assess and care for all dimensions of need of the patient: physical, social, psychological and spiritual

care for patients in the community if adequately supported

A review of how these 4 aspects are being put into operation in primary care internationally may help the development in the EM region.

First challenge: caring for people with all life-threatening illnesses

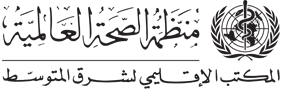

A century ago, and currently in some developing countries, most people died of infectious diseases, accidents or childbirth, aged 46 years on average, with little disability before death. Nowadays in the EM region the average age of death in most countries is above the age of 70 years and noncommunicable conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, are the main causes of death – usually after a significant period of disability [12]. The causes of death in this modern age can be illustrated well in United Kingdom (UK) primary care, where a family doctor, who has about 1800 patients on his or her registered list, has 20 deaths on average per year. Of these deaths, 5 are from cancer, 6 from organ failure (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, liver failure, renal failure) and 7 from frailty (either physical frailty or dementia). Only about 2 of the 20 die totally unexpectedly (Figure 1). The trajectories that these illnesses often follow have been well described making it more feasible for health-care providers to identify the palliative care needs of patients in the community [13].

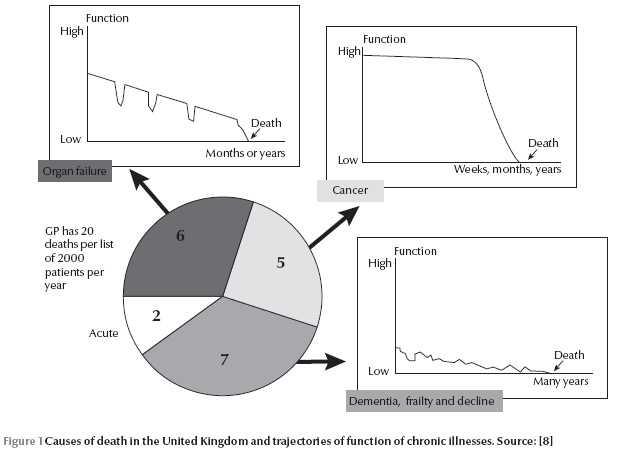

Second challenge: starting a palliative care approach early in the disease process

With cancer, traditionally there was a period when a cure was attempted and then when cure was no longer possible, palliative care was provided. The new and better concept is that supportive and palliative care should start at diagnosis of a life-threatening illness and gradually increase while disease-modifying care may decrease (Figure 2). This model and understanding can be applied to all people with a progressive illness including organ failure and frailty [14,15]. As debility increases from specific illnesses or general frailty, people can be considered for a palliative approach. Provision of palliative care should be triggered not by diagnosis, or even prognosis, but according to need. One example of a specific trigger for consideration for a holistic palliative approach might be when a patient is housebound. Yet another criteria could be the need of a certain amount or hours of care in the community.

In the organ failure and frailty trajectories, it has previously been more difficult to conceptualize and decide when a palliative care approach might be clinically appropriate. However, events or triggers such as a hospital admission might be utilized to consider if a supportive approach is now appropriate for that individual patient. Alternatively, there might be clinical indicators such as grade 4 heart failure (i.e. breathlessness at rest) to trigger this approach, or even the “surprise question”. This question is where a physician asks himself or herself the question, “Would I be surprised if this patient were to die in the next year?” If the answer is “no” this means that the patient might die and therefore a plan should be started “just in case the patient does die”. Research suggests that most patients with advanced illnesses appreciate the opportunity to talk to a physician about their future [16,17].

Overzealous treatment later in the course of all these types of illnesses, especially in the very last days of life, can increase suffering without any prolongation of life. This can be prevented by diagnosing imminent death, the second “key transition” in end-of-life care and starting the patient on an end-of-life care pathway, such as the Liverpool Care Pathway [18,19]. This ensures, among other things, the consideration of stopping any unnecessary treatments and tests.

Third challenge: meeting all dimensions of need, physical, psychological, social & spiritual

It is now recognized in the USA and increasingly in Australia and the UK that everyone has spiritual needs when faced with serious life-threatening illness. The accepted definition of spiritual needs used internationally is “needs that relate to the meaning and purpose of life” [20]. People may or may not use religious vocabulary to express these. If the spiritual issue or need causes the person distress, it is then called “spiritual distress”. If such distress is upsetting the person, such as interfering with sleep or their ability to work, then this should be identified and addressed by someone because such distress impinges on other areas, making pain more painful and anxiety less bearable, and increasing health service utilization. In a setting where spirituality and religion play a major role in everyday life, it is essential to address the spiritual dimension of death and dying with patients and their families.

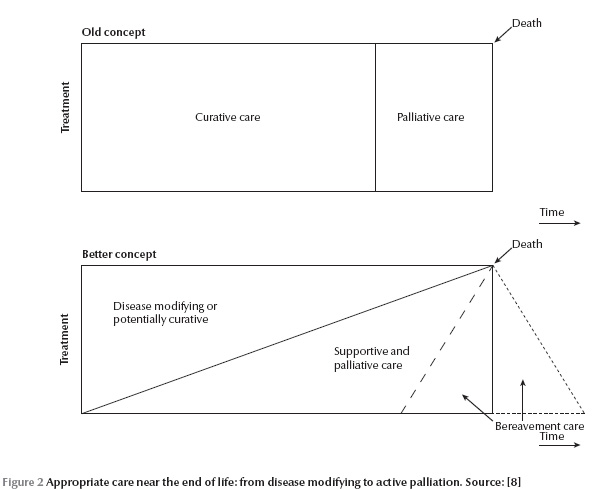

Dying is a 4-dimensional activity; it is more than physical. Our research team found that in lung cancer, at least, the social decline runs in parallel with the physical decline (Figure 3). Psychological distress can be expected at the time of diagnosis, after initial treatment when the patient returns from the hospital, at recurrence or disease progression, and then again in the terminal stage. Unsurprisingly it was when someone was anxiously coming to a diagnosis that also they were thinking about the meaning and purpose of life. It would appear that the spiritual trajectory in these patients with lung cancer paralleled the psychological one. The physical and social run together as do the psychological and spiritual [16]. It is worth thinking about trajectories because we can then plan 4-dimensional care according to what the needs of the patients are likely to be and we can plan timely care when these needs are likely to arise. Family carers, who have also been shown to have similar multidimensional trajectories at the end of life, can also be supported by family physicians [21].

Fourth challenge: providing end of life care in the community

In the UK, although it is believed that over 50% of people would prefer to die at home if possible, only 19% of people do in fact die at home. Although similar data are not available from the EM region, research has shown that people dislike hospitalization [6]. In the last decade, Dr Keri Thomas has pioneered the development of the Gold Standards Framework of Care which is at present used in over 80% of UK practices. It gives a structure for doctors and community nurses to organise and coordinate care around general practices. It highlights the “7Cs” that are vital for quality end-of-life care in the community: communication, coordination, control of symptoms, continuity of care, continued learning, carer support and care in the dying phase [22]. A number of evaluations are demonstrating that this framework is improving coordination among family physicians and community nurses, continuity of care and patient and family satisfaction [23]. This model can be used to develop palliative care programmes in the community in the EM region.

Primary care leading in to palliative care, with a common philosophy

When the doctor/patient relationship is already established, issues of building trust and mutual understanding that are essential to the therapeutic relationship are already present. This allows the family physician to provide palliative care in the context of an established relationship. The biopsychosocial model of care that is at the core of the philosophy of family medicine is shared with the palliative care approach, and spiritual and religious needs may also be considered [24,25]. Research shows that many patients want to talk about the future with their doctor but doctors may fear to do this lest the patient loses hope. Thus opportunities should be made by doctors to let patients raise these sensitive issues [26]. Family physicians are already trained to provide patient-centred care in the context of family and community, and family physicians are in the position to be able to address grief, bereavement and caregiver issues and identify individuals within the family as resources.

Palliative care can be built into existing primary care systems in the region by giving primary care physicians the tools to provide palliative care to their patients. Palliative care has been developed quickly and successfully in settings where it was integrated in the primary care system [27]. Given adequate training, resources and access to specialist support, family physicians can provide end-of-life care to most patients. Providing primary palliative care could encourage the extension of the palliative care approach to people with non-malignant conditions. Patients with life-limiting conditions, such as dementia, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and kidney failure often have a more prolonged illness course and comparable needs and concerns [28]. Indeed in the EM region only 7% of patients nowadays die from cancer, so the emphasis on primary palliative care is caring for all, not according to diagnosis, nor even prognosis, but according to need [12].

Conclusion

Thus there are 4 challenges or opportunities for primary care physicians to provide palliative care. Firstly, to look beyond cancer and help people at the end of life with all different illnesses: we should not palliate according to diagnosis or even prognosis but according to need, which is usually a sum of a number of co-morbidities. The second opportunity is to help earlier rather than later, when input is strategic and formative, and when emotional needs are often acute. Thirdly, primary care physicians can support all dimensions of need beyond the physical even to the spiritual. Fourthly primary care physicians can try to help more people spend more time in the setting they really want, often in the community with their friends and relatives in a familiar setting.

Palliative care should be integrated into all health and social care settings, especially primary care, so that doctors and nurses can identify when a shift from trying to cure the patient to trying to improve their quality of life is considered timely. Physicians should then discuss this with their patients and their patients’ relatives, and together plan their future care, to maximize the quality of their life and death in due course [29]. This approach should be taught at undergraduate and postgraduate levels in all medical and nursing schools and may prevent the overzealous treatment that some patients receive at the end of life [30].

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer. WHO definition of palliative care. (http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/, accessed 14 December 2011).

- Murray SA, Sheikh A. Care for all at the end of life. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2008, 336:958–959.

- Ellershaw J, Dewar S, Murphy D. Achieving a good death for all. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2010, 341:c4861.

- Temel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010, 363:733–742.

- Towards a strategy for cancer control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Cairo, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2009 (WHO-EM/NCD/060/E).

- Doumit MAA, Huijer H, Kelley JH. The lived experience of Lebanese oncology patients receiving palliative care. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 2007, 11:309–319.

- Back AL et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2009, 169:474–479.

- Murray SA et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. Clinical Review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2005, 330:1007–1011.

- Daher M et al. Lebanon: pain relief and palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2002, 24:200–204.

- Stjernswärd J et al. Jordan Pallaitve Care Initiative: a WHO Demonstration Project. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2007, 33:628–633.

- Al-Shahri MZ et al. Palliative care initiative for the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A proposal. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 2004, 24:465–468.

- World Health Organization. Health statistics and health information systems. Disease and injury regional estimates. Regional burden of disease estimates for 2004. (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional/en/, accessed 14 December 2011).

- Lynn J. Reliable comfort and meaningfulness. Making a difference campaign. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2008, 336:958–959.

- Palliative care: the solid facts. Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2004.

- Murray SA. Meeting the challenge of palliation beyond cancer. European Journal of Palliative Care, 2008, 15:213.

- Murray SA et al. Dying of lung cancer or heart failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2002, 325:929–932.

- Doumit MA, Abu Saad HH. Lebanese cancer patients: Communication and truth-telling preferences. Contemporary Nurse, 2008, 28:74–82.

- The Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool. Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (LCP) (http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/liverpool-care-pathway/index.htm, accessed 28 December 2011).

- Boyd K, Murray SA. Recognising and managing key transitions in end of life care. British Medical Journal, 2010, 341:c4863.

- Grant E et al. Spiritual issues and needs: perspectives from patients with advanced cancer and non-malignant disease. A qualitative study. Palliative & Supportive Care, 2004, 2:371–378.

- Murray SA et al. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family caregivers of patients with lung cancer: secondary analyses of serial qualitative interviews. British Medical Journal, 2010, 304:c2581.

- The gold standards framework. The essentials of GSF (http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/About_GSF/TheEssentialsofGSF, accessed 14 December 2011).

- Shaw KL et al. Improving end-of-life care: A critical review of the Gold Standards Framework in primary care. Palliative Medicine, 2010, 24(3):317–329.

- Murray SA et al. Patterns of social psychological and spiritual decline towards the end-of-life in lung cancer and heart failure. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2007, 34:393–402.

- Grant L, Murray SA, Sheikh A. Spiritual dimensions of dying in pluralist societies. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2010, 341:c4859.

- Barclay S, Maher J. Having the difficult conversations about the end of life. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2010, 341:c4862.

- Murray SA, Kik JY. Bridging the End-of-life gap. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 2008, 37:142–144.

- Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Palliative care in chronic illness. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2005, 330:611–612.

- Seymour JE, French J, Richardson E. Dying matters: let’s talk about it. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2010, 341:c4860.

- Murray SA. How can palliative care deal with overzealous treatment? Advances in Palliative Medicine, 2009, 8:89–94.