Research article

A.R. Khowaja,1 R. Karmaliani,2 R. Mistry 3 and A. Agha 4

الانتقال إلى المستشفيات المعززة للصحة: توئيم الإطار العالمي ليتلاءم مع باكستان

آصف راذا خواجا، روزينا كرملياني، روزينا مستري، أجمل آغا

الخلاصة: تشجِّع منظمة الصحة العالمية المستشفيات على أن تصبح مستشفيات معززة للصحة، ولكن لم يستقص أحد الباحثين من قبل مدى مواءمة هذا المفهوم في باكستان. وقد درس الباحثون التصورات لدى المعنيين بالرعاية الصحية حول الاستراتيجيات وخطة العمل ذات الأولوية للتشجيع على المستشفيات المعززة للصحة في باكستان. وأجرى الباحثون دراسة كيفية في عام 2007، أجروا خلالها مقابلات مع مصادر المعلومات من الشخصيات الرئيسية، وعقدوا مناقشات في مجموعات التركيز مع المعنيين بالرعاية الصحية في كراتشي. وأجروا تحليلاً بحسب المواضيع، مع تصنيف المواضيع الناتجة ضمن فئات. لقد كانت التصورات حول المكونات الرئيسية للمستشفيات المعززة للصحة على أنها «إطار معياري»؛ إلا أنه جرى التأكيد على الأعمال ذات الأولوية التي تلبِّي «الاحتياجات الأساسية» للمرضى، والعاملين، والمجتمع. وقد اشتمل ذلك على المرافق الأساسية للراحة، والصحة الشخصية، والسلامة، والأمن، والدعم النفسي. ويرى الباحثون أن تغيير الذهنية التقليدية للعاملين الرئيسيين من العلاج إلى الرعاية، والتعرف على العاملين الأساسيين، والارتقاء بمستوى الوعي، والتعاون، سوف يرسِّخ جهود الدعوة للمستشفيات المعززة للصحة في باكستان.

ABSTRACT The World Health Organization encourages hospitals to become Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH) but adapting this concept to Pakistan has not been investigated. We explore perceptions of healthcare stakeholders about strategies and a priority action-plan to encourage HPHs in Pakistan. We conducted a qualitative study in 2007 where key-informant interviews and focus group discussions were held with healthcare stakeholders in Karachi. Thematic analysis was done and emerging themes were categorized. The HPH core components were perceived as the “standard framework”; however more emphasis was placed on priority actions as to satisfy “basic needs” of patients, staff and the community. This included basic facilities of comfort, health, hygiene, safety, security and emotional support. A change in the traditional mindset from cure to care and identification of key personnel, awareness-raising and cooperation would strengthen advocacy efforts for HPH in Pakistan.

Transition vers des hôpitaux engagés dans la promotion de la santé : adaptation d’un cadre mondial au Pakistan

RÉSUMÉ L’OMS encourage les hôpitaux à devenir des hôpitaux engagés dans la promotion de la santé, mais l’adaptation de ce concept au Pakistan n’a pas été étudiée. Nous avons dégagé les perceptions des parties prenantes dans le secteur des soins de santé concernant les stratégies et le plan d’action prioritaire afin d’encourager les hôpitaux engagés dans la promotion de la santé au Pakistan. Nous avons conduit une étude qualitative en 2007 au cours de laquelle des entretiens avec des informateurs clés et des groupes de discussion thématiques ont été organisés à Karachi avec les parties prenantes du secteur des soins de santé. Une analyse thématique a été réalisée et les thèmes dégagés ont été classés. Les composantes essentielles des hôpitaux engagés dans la promotion de la santé ont été perçues en tant que « cadre de référence » ; toutefois, l’accent a été mis sur les actions prioritaires afin de satisfaire les « besoins fondamentaux » des patients, du personnel et de la communauté. Ces besoins comprennent des installations de base où l’on trouve confort, santé, hygiène, sécurité, sûreté et soutien psychologique. Une évolution des mentalités vers les soins préventifs, alors qu’elles sont traditionnellement axées sur les soins curatifs, et l’identification des personnels clés, la sensibilisation et la coopération pourraient renforcer les efforts de plaidoyer en faveur des hôpitaux engagés dans la promotion de la santé au Pakistan.

1Department of Paediatrics & Child Health; 2School of Nursing; 4Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan (Correspondence to A.R. Khowaja: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it )

3Aga Khan Health Services, Karachi, Pakistan.

Received: 05/01/10 accepted: 18/03/10

EMHJ, 2011, 17(10): 738-743

Introduction

Today, the World Health Organization (WHO) encourages and inspires hospitals to embrace the ideology of health promoting hospitals (HPHs) globally [1]. A HPH is defined as, “a hospital that develops a corporate identity, embraces the aims of health promotion and demonstrates a healthy culture and structure within the hospital” [2]. Hospitals have great potential to influence health promotion at large given their reach and services provided [3].

The Ottawa Charter was the first declaration on health promotion made in 1986; and the concept of health promotion at hospital evolved as the fifth strategy of the same charter [4]. Although the initial efforts to institutionalize evidence-based HPH settings were in Europe, this approach is now internationally recognized and recommended for other regions. In this regard, an international HPH network has been gaining popularity, as more regions are now taking interest in adapting HPH standards and getting their hospitals internationally accredited [5,6]. Similarly, the evolving emphasis on disease prevention and health promotion within the developing world provides an opportunity to apply health promotion in the hospital setting [7].

Developing countries, including Pakistan, face considerable public health challenges as politically driven healthcare plans have led to clinical services consistently taking a bigger chunk of the healthcare budget, leaving meagre resources for disease prevention and health promotions [8]. Given the dynamic role of HPH in providing holistic care under one roof and benefiting patients, care-takers, hospital staff and community at large, transition towards HPH would seem an appealing, cost-effective, needed approach for Pakistan at this time [9].

WHO provided the international core components and standards for HPH, however, certain scepticism and dilemma prevailed among various European countries when it came to institutionalizing the idea [1,5]. There is a paucity of information about strategies and a coherent roadmap for our local context in order to adapt internationally endorsed HPH settings to Pakistan. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore perceptions of healthcare stakeholders about context-specific strategies and a priority action-plan to encourage and adapt health promotion activities in hospital settings in Pakistan.

Methods

This study involved qualitative research to explore context-specific strategies regarding institutionalizing HPH in Pakistani settings. A qualitative research design was used in order to explore subjectivity of the theme under study so as to generate hypotheses for further studies [10].

This study was conducted between July and August 2007. The study participants were purposively selected from:

Public and private health sector to represent administration and healthcare providers (doctors and nurses) at 2 tertiary care hospitals (Aga Khan University, Hospital and Jinnah Postgraduate & Medical College Hospital representing the private and public sector respectively)

Health decision/policy-makers at selective health departments of Sindh province

Representatives from the Federal Ministry of Health

Representatives in Karachi, Pakistan of United Nations organizations (UNFPA, UNICEF and WHO) and the donor agency (US-AID).

This study received approval from the ethical review committee of the Aga Khan University, and participation was on voluntary basis, upon obtaining written consent.

Key informant interviews were held with 11 participants as well as 2 focus group discussions (1 at each public and private hospital) with 6 participants (3 nurses and 3 doctors who met the eligibility criteria and consented to participate). The participants for the key informant interviews were chosen based on their knowledge or expertise on the topic being studied (WHO’s 5 core components of HPH) [5,11] with at least one year of full-time experience in the relevant field.

A semi-structured questionnaire was developed using WHO’s 5 core components of HPH, i.e. hospital’s management policy, patient assessment, patient information and intervention, promoting a healthy workplace and continuity and cooperation [5]. The questionnaire was piloted on a similar group of participants before administering to the study participants in the key informant interviews and focus group discussions. The interviews and focus group discussions were taped, and notes and observations were recorded.

The thematic analysis was done using qualitative research software QSR NVivo, 2.0 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Perceptions were coded on free nodes, which were later categorized to hierarchical tree, as parent, child and sibling nodes to develop emerging themes and sub-themes [12]. These themes and sub-themes were elaborated, interpretations were made and data triangulation was done between key informant interviews and focus group discussions.

Results

The participants’ perceptions highlighted various strategies to promote health promotion activities in hospitals and revealed strategic steps to encourage and sustain transition towards HPH in Pakistan. The following themes and sub-themes emerged from the key informant interviews and focus group discussions under the 5 core components for health promotion activities at hospital.

Hospital’s management policy on health promotion

The hospital management policy on health promotion was perceived as the “founding stone”. The roles of the hospitals managers and those working with the social sectors were very much highlighted in this regard. Although distinctive hospital policy on health promotion was largely perceived to influence staff practices, the need to draft a national health promotion policy in Pakistan was stressed.

Health promotion for patients and their attendants

The study participants perceived patients as “external customers” and care-takers as “ambassadors” to carry a generic message of health promotion to their immediate community. The participants interchangeably used the term “health education” as the “traditional approach” to refer to health promotion for patients and attendants at the hospital. The participants also emphasized the lack of a healthy structure and participatory health promotion activities as the challenges for health promotion activities.

Healthy physical structure: basic facilities of comfort, patient safety & support

The participants largely perceived that a healthy hospital environment would leave a “first and ever-lasting impression” on patients and attendants. The perceived needs were further elaborated as: availability of purified drinking water, clean washrooms, ventilated inpatient area, comfortable beds, clean linen, hygienic food, stretchers for safe inpatient transfer, proper disposal of sharp objects and needles to prevent accidental injuries. The key informants also reported emotional support for patients as integral to early recovery, and therefore recommended the establishment of integrated patient support departments, such as patient complaints, patient counselling, patient welfare, quality assurance and patient referral departments.

Health promoting activities: participatory health education, patients’ rights and empowerment

The “participatory approach” was perceived to bring significant change in the behaviour to promote health. The focus group discussions reported, “While treating a female patient with a family history of breast cancer, the healthcare provider should also assess and counsel her for early screening”. The participants further recommended hospital staff to communicate with patients and attendants respectfully and involve them in patient care plan and decision-making so that they feel empowered. In order to ensure health education for patients and families as a compulsory component of care, the participants recommended the development of health education indicators and standard protocols, and the conduct of surprise audits as part of the routine services. The “sharing of the right information at the right time” was considered an integral factor to increase self-reliance and achieve compliance with care and promotion of healthy living.

Making hospital a healthy workplace for staff

Staff members were largely perceived as “internal customers” at the hospital; therefore, their satisfaction with the work place and their good health were considered equally important in order to satisfy the patients.

Hospitals’ physical structure: basic facilities of comfort, safety and security

The study participants at the public hospital perceived that female staff (both medical and paramedical) constitute a large proportion of the workforce at any hospital; therefore, provision of their basic needs, most importantly safety and security, was much needed. These facilities include having staff common rooms, clean female toilets, a staff cafeteria, transport facilities, and the availability of universally recommended safety measures to protect them from physical or emotional hazards. A focus group discussion participant noted, “There has to be hand washing facilities in each ward, availability of soap, gloves, face masks, needle cutter, dustbin and other safety measures”.

Health promoting activities: health screening, recreational activities & empowerment

All study participants perceived the need for periodic health screenings for staff, flexible working hours for lactating mothers and recreational activities to sustain the health of the staff. Moreover, staff members could be empowered by involving them in decisions that indirectly influence the scope of their work at the hospital. A key informant revealed, “Hospitals should promote a democratic or participatory environment, where staff could comfortably discuss their issues, concerns, and needs with the hospital management”.

Health promotion for the community: thinking outside the box & capacity building

The participants revealed that hospitals should “broaden the scope of services beyond the four walls” of the hospital and adopt a “holistic approach” to promote the health of the community. The common health problems encountered at hospital were perceived as an opportunity to roll-out public health strategies to prevent further associated morbidity and mortality among the target population in the community. One key informant revealed, “When there are any crises such as floods, we send our hospital staff out to provide healthcare services. Then why not to send staff into the community for health promotion?”. The outreach efforts by hospitals, such as, interactive health awareness sessions for community people, school health and industrial health programs were perceived to build local capacity.

Hospital collaboration with other social sectors

All participants recommended multisectoral collaboration as “the key” to achieve health for all and hospitals can act as a “change catalyst”. Health promotion interventions were also recommended through establishment of small health committees at the community level, networking with nongovernmental organizations, United Nations donor agencies and the local media. A focus group participant noted, “Everybody might be willing to cooperate, but it is the initiative that matters!”.

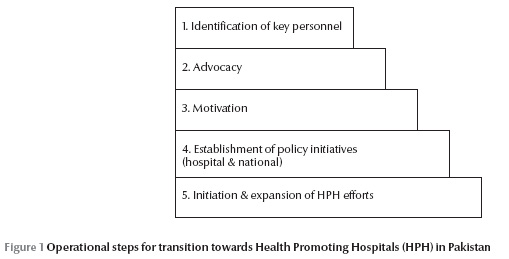

Strategic steps for transition towards HPH

The participants’ perceptions were organized as to form strategic steps towards adapting HPH in Pakistan. Figure 1 presents levels as to where to start and roadmap for HPH.

Identification of “key personnel” and representation from all levels (health care staff/administration staff at the hospital, health committee members at the community level, health decisions/policy-makers and donor agency representatives) was considered crucial to start with. The participants recommended mass awareness of stakeholders about the need for health promotion in order to change the mindset from cure to care. Such mass awareness would further strengthen advocacy efforts, which indirectly creates “demand” for health promotion. A key informant noted, “We go with demand, and this translates our priorities”. The motivation among healthcare stakeholders by means of a “recognize and incentivize approach” was also perceived to go side by side to meet the “demand and supply” for health promotion. The study participants also reported that transition to HPH primarily requires “collaborative efforts” among all key personnel. A key informant noted, “One person cannot do anything, but collectively they can make a difference”. Nevertheless, a common notion prevailed that a positive trend towards HPH can be initiated and sustained only when there is “local role model” for others hospitals, “political will and policy support” in Pakistan.

Discussion

Health promotion at hospitals introduces an opportunity for hospitals to broaden the scope of their work and have a positive impact on the health of the population by addressing social determinants of health. Research findings have shown HPH to benefit all its stakeholders, patients, their attendants, hospital staff, proprietors of hospitals and health regulatory agencies [13]. The transition to HPHs is historically linked to achieving health for all and there have been a series of influential movements in the developed world including the Budapest Declaration in 1991 and the Vienna Recommendation in 1997 [2,14].

Our study underscores context-specific strategies, and provides hospitals a framework of priority actions and strategic steps for adapting international components of HPH to Pakistan. The perceptions of study participants were in line with the 5 core components of HPH [5,15]. A factor considered important was the basic need to make the hospital environment healthy both for internal and external customers. A study in 2003 endorses this point reporting that a that nurses’ work on health promotion was often made more difficult by the lack of staff, space, equipment and cleanliness [16]. This finding raises a critical concern: how can staff incorporate health promotion activities as part of their practices when their basic needs (health, hygiene, safety, security) are not adequately addressed? Our study uncovered priority actions needed to meet basic needs, which required neither sophisticated technology nor lavish facilities to create a healthy workplace. The concept of basic needs can be related to the Maslow hierarchy of physiological needs, in order to motivate the staff and create a healthy workplace [17].

When participants expressed their views about HPH core components, the theme of hospital/national policy was emphasised only by the donor agency representatives. However, the focus group participants (doctors and nurses) were concerned more about the operational aspects than the policy agenda, such as inclusion of patients in decisions about quality and the approach to the delivery of the health care from the hospital. This finding could be attributed to the limited exposure of doctors and nurses to health policy matters; however, this assumption was not supported by any literature. Our study also indicated certain operational challenges related to human resources, a need for a shift in focus and clarification of roles in order to fully adapt to the notion of HPHs in Pakistan. A lack of clear strategies, inadequate resources, lack of training facilities and a lack of priority for health promotion were reported as major challenges when HPH was introduced in developed countries [1].

The strategic steps that evolved from the participants envisaged representation of key personnel at each level, with focus on community and hospital staff. A study from Denmark suggested that nurses play an important role in incorporating health promotion practices at the hospital [18].

An important finding from this study was the urgent need for advocacy to create a ‘demand and supply’ for primary healthcare by sensitizing the community and stakeholders. The literature suggests that a health devolution plan to the district level is imperative, and crucial, if primary health care is to be improved in Pakistan [19]. It was recommended that hospital administrators think outside the box and start liaison with collaborative partners (civil society organizations) and those working in the social sector. This finding coincide the literature that hospitals exist as a “whole organization”, focusing on health promotion right from the small unit to a wider public health role, appreciating the responsibility of managers and decision-makers [20,21].

Our study was an effort to explore operational aspects using the global HPH framework with context-specific priority actions and strategic steps to adapt such an initiative to Pakistan. Our results are replicable to hospitals both in the public and private sector that are willing to adapt to the internationally recognized concept of HPH in Pakistan. The scope of our study was limited to healthcare stakeholders only; however, we recognize the perspective of the community and the social sector are equally important for advocating demand for health promotion at hospitals. Nevertheless, this study paves the way for future case-based studies to highlight the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder, and to pilot suggested strategies for health promotion at hospitals in Pakistan.

Conclusion

Transition from cure to care by adapting internationally recognized HPH settings can be achieved in Pakistan using the global framework with our context-specific priority actions. Pakistan. Integrated efforts are required to adapt to HPH to the Pakistan setting; this will only be possible when healthcare providers and policy decision-makers start realizing the need for such initiative. Hospitals need to work closely with collaborative partners in line with new policies addressing health promotion priorities. Social mobilization and awareness programmes for the community will intensify the demand for such a transition and strengthen advocacy arguments overall.

References

- Whitehead D. The European Health Promoting Hospitals Project – how far on? Journal of Health Promotion International, 2004, 19:259–267.

- The Budapest Declaration of Health Promoting Hospitals. (http://www.ongkg.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Grunddokumente/Budapest-Declaration.pdf, accessed 15 August 2011).

- Aiello J et al. Health Promotion-a focus for hospitals. Australian Health Review, 1999, 13:90–94.

- Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion Ottawa, 21 November 1986 (WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1) (http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf, accessed 15 August 2011).

- Standards for health promotion in hospitals. Copenhagen World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2004 (http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/99762/e82490.pdf, accessed 15 August 2011).

- Health Promoting Hospitals Network (webpage) (http://www.euro.who.int/healthpromohosp, accessed 15 August 2011).

- Hafez G. Health Promoting Hospitals in developing countries. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Health Promoting Hospitals. Vienna, Austria, G. Conrad Health Promotion Publications, 1997:45–47.

- Nishtar S. Budget 2006–07—an ode to health. Bluechip, 2006, 3(25):1–3 (http://www.heartfile.org/pdf/9_Budget2006_VP.pdf, accessed 15 August 2011) .

- Khowaja AR et al. Potential benefits & perceived need for health promoting hospitals in Pakistan: a healthcare stakeholder’s perspective. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 2010, 60(4):274–279.

- Rossman G, Marshall C. Designing qualitative research: how to conduct the study, 2nd ed. London, UK, SAGE Publication, 1995:38–43.

- Burns N, Grove S. Understanding nursing research: building an evidence-based practice, 4th ed. St Louis, Missouri, Saunders Elsevier, 2007:344–377.

- Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook, 2nd ed. London, Sage Publications, 1994:44–46.

- Youens W. Health promotion in hospitals: getting attention by showing leaders the benefits. The Health Promotion Exchange, 2001/2002, Fall/Winter:2–3. (http://216.95.229.96/pdf/HPE-Fall-2001.pdf, accessed 15 August 2011).

- The Vienna Recommendations on Health Promoting Hospitals. (http://hpe4.anamai.moph.go.th/hpe/data/hph/Viena_Recommendation.pdf, accessed 15 August 2011).

- Pelikan J, Karl K, Christina D. The Health Promoting Hospital (HPH): concept & development. Journal of Patient Education and Counseling, 2001, 45:239–243.

- Olden P. Why hospitals offer health promotion: Perspectives for collaborating with health promotion practitioners. Journal of Health Promotion Practice, 2003, 4(1):51–55.

- Benson S, Dundis S. Understanding and motivating healthcare employees: integrating Maslows hierarchy of needs, training and technology. Journal of Nursing Management, 2003, 11(5):315–320.

- Oladimejiv V. Role of nurses in health promotion for older adults with hospital setting. Copenhagen, Health Promoting Hospital Network, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 1997.

- Shaikh B, Rabbani F. The District Health System: a challenge that remains. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2004, 10:208–14.

- Coakley AL. Health promotion in a hospital ward; reality or asking the impossible? Journal of Royal Society of Health, 1998, 118:217–220.

- Whitehead D. Workplace health promotion: the role and responsibility of health care managers. Journal of Nursing Management, 2006, 14(1):59–68.