S.M. Adib,1 N. Tabbal,2 R. Hamadeh 3 and W. Ammar 4

الوبائيات الجغرافية في منطقة صغيرة: معدل حدوث السرطان في بعقلين، لبنان: 2000-2008

سليم أديب، نبيل طبال، راندة حمادة، وليد عمار

الخلاصـة: لا تتيح البيانات المتراكمة التي يقدّمها السجل الوطني للسرطان في لبنان تمييز معدلات حدوث السرطان في المناطق الصغيرة. وقد أجرى أعضاء مدربون في المجتمع مسوحات للسكان الدائمين في بلدية بعقلين باستخدام أسلوب التشريح اللفظي. وشمل المسح 1042 من المنازل التي كان فيها أحد السكان على الأقل يعيش في بعقلين بشكل دائم في الفترة 2000-2008، وهكذا فقد غطَّت البيانات 4330 شخصاً بما يعادل 34143 سنة من الملاحظة. وخلال فترة الملاحظة أبلغ عن 56 حالة سرطانية جديدة، وكان وسطي العمر وقت الإبلاغ يتفاوت تفاوتاً يُعْتَدُّ به إحصائياً بين الرجال (77 عاماً) والنساء (56 عاماً). وكان أكثر أنماط السرطان شيوعاً سرطان الرئة (%20)، يتلوه سرطان القولون والمستقيم (%12.5) وسرطان الثدي (%9). وكان المعدل الخام التقديري لحدوث السرطان 164 حالة لكل مئة ألف شخص/عام؛ وهو أعلى بمقدار يُعْتَدُّ به إحصائياً لدى الرجال (194) مما هو عليه لدى النساء (130)، وأقل بكثير من مجمل الرقم الوطني (218). وكان السكان الدائمون في بعقلين أطول عمراً من أعمار مجمل اللبنانيين، إلا أن معدل حدوث السرطان أقل بشكل واضح من الرقم الوطني. وتلفت هذه النتائج النظر إلى أهمية الحِفَاظ المتواصل على التلوث البيئي المنخفض، وإلى أهمية أنماط الحياة الصحية في الغذاء، والامتناع عن التدخين في وقاية السكان من السرطان حتى الآن.

ABSTRACT Aggregate data of the National Cancer Registry in Lebanon cannot discriminate cancer incidence in small areas. Trained community members surveyed the permanent population of the Baakline municipality using the verbal autopsy approach. We surveyed 1042 households with at least 1 member living permanently in Baakline during 2000–2008. Data covered 4330 persons yielding 34 143 years of observation and 56 new cases of cancer were reported. Median age at diagnosis varied significantly between men (77 years) and women (56 years). The most common types were lung cancer (20%) followed by colorectal (12.5%) and breast (9%). Estimated crude cancer incidence rate was 164 cases/100 000 persons/year, significantly higher in men (194) than women (130), and much lower overall than the national figure (218). The permanent Baakline population is older than that of Lebanon itself, yet the cancer incidence rate is markedly lower than the national figure. This finding pleads for serious efforts to preserve the low environmental contamination and the healthy lifestyles in food and tobacco abstinence that have protected the population so far.

Épidémiologie géographique dans une petite zone : incidence du cancer à Baakline (Liban) entre 2000 et 2008

RÉSUMÉ Les données globales du registre national du cancer au Liban ne permettent pas de distinguer l'incidence du cancer dans des petites zones. Des membres de la communauté formés ont interrogé la population permanente de la municipalité de Baakline à l'aide de la méthode de l'autopsie verbale. Nous avons enquêté auprès de 1042 ménages au sein desquels au moins un membre a habité de manière permanente à Baakline entre 2000 et 2008. Les données concernaient 4 330 personnes, pouvant représenter 34 143 années d'observation. Pendant les neuf années de la période d'observation, 56 nouveaux cas de cancer ont été rapportés. L'âge médian au moment du diagnostic variait significativement entre hommes (77 ans) et femmes (56 ans). Les types de cancer les plus courants étaient le cancer du poumon (20 %), le cancer colorectal (12,5 %) et le cancer du sein (9 %). Le taux brut estimé de l'incidence du cancer était de 164 cas/100 000 personnes/an ; il était nettement plus élevé chez les hommes (194) que chez les femmes (130), et globalement bien plus faible que le taux national (218). La population permanente de Baakline est plus âgée que celle du Liban, cependant l'incidence du cancer est très inférieure au chiffre national. Ce résultat appelle d'importants efforts pour préserver le faible degré de contamination de l'environnement et les modes de vie sains, notamment pour ce qui est de l'alimentation et de l'abstinence tabagique, qui ont protégé la population jusqu'à aujourd'hui.

1Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Saint-Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon (Correspondence to S.M. Adib:

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

). 2INSERM U897, ISPED, Université Victor Segalen, Bordeaux, France. 3Primary Healthcare Department; 4Ministry of Public Health, Beirut, Lebanon.

Received: 29/08/11; accepted: 12/12/11

EMHJ, 2013, 19(4):320-326

Introduction

Systematic epidemiological data concerning cancer in Lebanon have become available on a regular basis only recently through the National Cancer Registry [1]. Most recently the incidence of cancer was estimated at about 180 cases per 100 000 population per year (2008), for a total annual case-load approximating 8000 new cases (unpublished data, Ministry of Health, 2008). Because of the relatively small number of new cases occurring annually in Lebanon, aggregate data of the National Cancer Registry cannot discriminate cancer incidence accurately even at the mohafazat (governorate) level. In particular, the way data are collected cannot respond to the needs of the population in specific areas of Lebanon to know more about trends in cancer incidence particular to their area.

Traditions in Lebanon still require that a deceased person should be buried in his/her original city, regardless of the place where death occurred. A person whose roots are in Baakline is highly likely to be buried there, even if the death occurred elsewhere in Lebanon or even abroad. When the body of a person who died abroad is not repatriated, the passing will be marked by the extended family in some form of social ceremony. As cancer incidence increases in Lebanon and worldwide, grieving ceremonies for persons dying from cancer will also increase. In a small community such as Baakline, this increase in cancer-associated deaths can become rapidly perceptible, notwithstanding the place of residence of the deceased person at time of diagnosis. In addition, a diagnosis of cancer is more frequent than in the past, and the stigma against disclosing it is eroding. All these factors may give the impression that cancer is becoming a much more serious problem than elsewhere. This impression can only be validated using quantitative methods, such as the measure of the actual cancer incidence in Baakline.

The Lebanese population is recorded in vital statistics not by place of residence but rather by place of family origin. A person recorded in Baakline may have been born outside the city, lived all their life elsewhere, and never even seen it in their entire lifetime. In reality, even among those born in Baakline, internal migration or expatriation will result in a large proportion, if not the majority, living most of their lives outside the city. Therefore, records in Baakline (and any other small town or village in rural Lebanon) will forever suggest a larger demographic dimension than in reality. When a person dies, they will be ultimately recorded as dead in Baakline, regardless of the place mentioned on the death certificate. These factors make it difficult to decide on the denominators to be used for the estimation of cancer incidence in a specific area, and on which cases should actually be included in the numerator. Hence, measuring local cancer dynamics can best be done when the confines of a stable, clearly defined population are defined first.

Other arguments plead in favour of a down-up approach from population to disease. Cancer is associated with endogamy, cultural lifestyle norms (food, drinks, tobacco use, etc.) and common environmental exposures [2]. Changes in those variables, which happen when people leave their original community, will lead to changes in cancer risks. Consequently, cancer incidence in Baakline or elsewhere can be assessed in a valid way only among those living there long enough to be exposed to a potential risk on a long-term basis, and to allow for that exposure to progress to pathology.

In 2009, a request was filed by the population of Baakline and surrounding areas, in the mountain caza (district) of Chouf (Central Lebanon) with the local Member of Parliament to provide evidence for or against a perceived increase in cancer incidence. This study responds to that community request. Baakline is a mid-sized, semi-rural, mountain town (altitude 900 m) 45 km south-east of Beirut. It has about 2800 households with a relatively affluent population of about 17 000, but the proportion of those who are actual year-long permanent residents is unknown.

The objectives of the field investigation reported here were: to establish a yearly denominator of permanent residents of the Baakline area for 2000–2008; to count all cases of death in each of those years, for all reasons, for all cancers, and for each type of cancer; to compute age-adjusted mortality and cancer-specific mortality rates in the Baakline area, and to compare those with national figures.

Methods

We carried out a door-to-door survey using the verbal autopsy method to measure the cancer incidence in Baakline between 2000 and 2008. All households with permanent residents existing within the confines of the municipality of Baakline were assessed. For the purposes of this survey, a permanent resident of Baakline was defined as a person who had no other permanent residence outside those confines before 2009.

The project was presented to the population in a town meeting and vetted by the “neighbourhood committees” representing families in each sector of Baakline. A data checklist was established to be completed in face-to-face interviews. This included household variables, information on cancer cases, and some selected environmental factors whose potential association was deemed of interest to the community. We trained 25 women from the neighbourhood committee (a women's association) on the interview checklist during 2 special sessions. This prepared then in a standardized way to deal with all possible situations that might arise when conducting the interviews. Following training, the surveyors started canvassing their respective neighbourhoods door-to-door to further explain the aim of the survey to the community and to obtain voluntary participation. In each household, 1 respondent was requested to provide accurate information on permanent household members who were still alive and also those who had died between 2000 and 2008. The entire encounter did not last more than 20 minutes.

When reluctance to share information was perceived in a household, a female committee member from another neighbourhood was brought into the process, and this simple step most often resulted in agreement to participate.

The process was confidential but not anonymous. Activities were supervised by a senior staff member located at the Municipality, who was in charge of trouble-shooting and had easy access to the research team in Beirut. Names and telephone numbers were obtained for validity and accuracy checks, which were conducted by the supervisor on questionnaires with missing, unclear or inadequate responses.

The age-sex composition of the permanent population, alive and dead between 2000 and 2008 was analysed. The cancer incidence rate was calculated using a denominator of person-years, and presented as incidence rate per 100 000 persons per year.

Demographic, clinical and environmental characteristics of cancer cases/households identified in the survey were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) and median or frequencies and percentages, depending on the variable involved. Differences were tested using adequate procedures and significance was established at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Description of the participating population

The surveyors identified 1042 households with at least 1 member living permanently in Baakline during the period of the survey (October 2009–March 2010). This represents about 1/3 of all households in Baakline. A few households refused initially to allow the survey team access, however, informal contacts and further clarification of the aims of the research resulted in a reversal of the refusal.

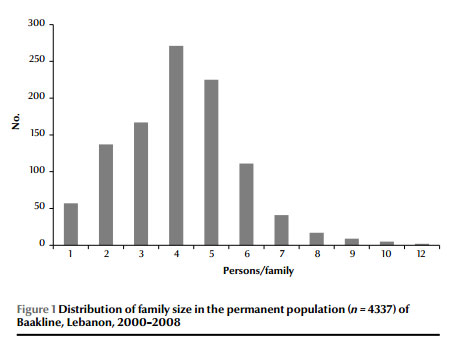

The family size per household was on average 4.8 (SD 1.8; median 5) persons. Only 5.5% of households included only 1 person and about 3% included ≥ 8 members (Figure 1).

The total number of individuals who were permanent residents at any time between 2000 and 2008 was 4330 persons. We found 47.8% were ≥ 40, (mean 39.8, SD 22.7) years. Compared to the general Lebanese population, the population surveyed in Baakline was older (median 29.8 years nationally versus 38.0 in Baakline) (Table 1) [2]. It included a lower proportion of women (46.4%) compared to national figures (49.7%) [3]. There were no meaningful differences in mean age between men and women. The survey population contributed a total 34 143 person-years of observation.

There were a number of reasons why a full 9-year observation period could not be obtained for 672 individuals; these included: travelling away from Lebanon (40%), moving away from Baakline (36%), death (23%) or birth (1%).

The crude death rate from all causes was 4.6 per 1000 per year; the crude birth rate was 0.2 per 1000 per year. Details on the age-sex distribution of the survey population compared to the general Lebanese population at mid-interval (CAS 2004) are shown in Table 1.

Cancer experience in Baakline

During the 9-year observation period, 56 new cases of cancer were reported; 62.5% were in men (versus 50% nationally) [1]. In 5 cases, the respondents were unable to clearly state the cancer sites, and another member of the family more acquainted with the details of that case was consulted. The mean age at diagnosis was 66.6 (SD 18.8; median 71.5) years. The median age at diagnosis varied significantly between men (77 years) and women (56 years) (P < 0 .01). The most common sites were lung (20%) followed by colorectum (12.5%) and breast (9%). Case-fatality was 57%, greater in men (63%) than in women (52%) (Table 2). The cancer-specific death rate was 1.3 per 1000 per year (n= 46). Figure 2 presents the relative distribution of cancer diagnosis by year which shows random patterns with no clear trends over time, suggesting an average of 6–7 new cases to be expected per year, in the absence of major shifts in the composition and exposures of the population.

Based on figures observed, a crude cancer incidence rate of 164 new cases per 100,000 persons per year could be estimated for the total population; significantly higher in men (194) than women (130). Overall cancer incidence unadjusted for age was lower in Baakline compared to the national figure (218 cases per 1000 in 2004). Adjusting for age would have brought the Baakline figures even lower, since its population was older than the national mean age, and was therefore judged to be of no added value to the study. The crude cancer incidence rate was higher than the national figure for men but for women it was lower (Table 3).

Environmental factors

Tables 4 and 5 provide details on several environmental factors such as sources of water used in the household and the indoor environment. Microwaves which may be sources of potentially dangerous radiations were present in 45% of households. Most households were free of any indoor smoke, either from cigarettes or narghileh (shisha). In almost all those which had smokers, the number rarely surpassed 1 per household. Few households were in direct proximity to agricultural land using pesticides (7.4%) or to electromagnetic fields generated by high-voltage electric power lines (2.7%). Comparison of households with and without cancers did not show any significant differences for any of these selected environmental factors.

Discussion

From the outset, the characteristics of the permanent population of Baakline which would be included in this door-to-door survey were particular. Compared to the Lebanese population, it was significantly older (2011 estimates) [3]. The proportion of those aged 60 and more was 22%, compared to 10% in the overall population [4]. This clearly reflects the depletion of the rural population through migration, which leaves older persons behind. Another finding emerged also from the survey: the proportion of elderly men was unexpectedly higher than that of elderly women. This unusual situation very likely reflects the social reluctance of children to leave an elderly mother, more than an elderly father, alone in the mountains as they move away, and the higher probability that elderly men more than elderly women would resist moving away, even when left alone in the house.

In the permanent population of Baakline, the incidence of cancer, unadjusted for age, was lower than the national rate (Table 3) [1] (adjustment was deemed irrelevant to the purpose of this study, since the population of Baakline is older than the population of Lebanon as a whole, and adjustment would therefore have increased the gap in rates). The difference was most marked in women, where incidence in Baakline was almost half the national rate. Another epidemiological difference was for age at diagnosis, favouring Baakline’s men (median age 77 years) compared to men in Lebanon as a whole (median age 63 years) [3]. There were no differences in this regard in women (median age 56 years).

The favourable findings for cancer in Baakline may be largely attributable to the healthy environment, as indicated some selected variables measured in this survey. Arguably, factors directly associated with lifestyle would also contribute to this finding. Those factors were not included in this survey because they cannot be validly measured for several persons over a 9-year period using 1 interview with 1 proxy respondent.

Although no other studies have been done in this area and no data are available, empirical observation and informal exchanges with community members largely suggest that lifestyles remain for the most part traditional and healthy. The protective effects of the mountain environment and/or lifestyle are further confirmed in the interpretation of epidemiological differences. When the risk factors are intrinsic, cancer occurs at the same age as in the rest of the population. The most common cancer in women, breast cancer, is caused by reproductive factors, and therefore occurs at the same age everywhere. Patterns of reproductive life are believed to remain traditional in Baakline (early age at marriage, larger families, longer breast-feeding periods, etc.) and may lead to a lower incidence of risk factors, and therefore lower incidence rates. These patterns will change inevitably with younger women, and therefore cancer in women may increase in the coming years, thus indicating the importance of awareness regarding early breast cancer detection as years pass by.

Men also display a significant resistance to cancer, which occurs in Baakline almost 15 years later than elsewhere in most cases. For men in general, the most common cancers were of the lung and colon, both widely associated with lifestyle, e.g. smoking and a diet low in fibre and rich in animal fats [2]. The behavioural risk factors we assessed are probably less prominent in Baakline, which may explain the delay in cancer incidence compared to elsewhere. However, the frequent finding of behaviourally-associated cancers among older men suggests that they may be a special risk group in the population, whose social environment should be investigated and improved, if possible.

There are very few studies specifically assessing differences in cancer incidence in mountainous and non-mountainous areas. A study from Kyrgyzstan found a lower incidence of oesophageal, pulmonary and breast cancers in ethnic groups historically living in mountainous areas [5]. The difference was attributed to the adaptation of those groups to mountain hypoxia, which may “function like a brake for the development of cancer tumours”. However, this study did not consider an alternative/contributing attribution to lifestyles between the traditional ethic groups in the mountains (mostly Kyrgyzs) compared to “newcomers” (Kazakhs and Russians).

A certain level of interaction seems to exist between environmental and lifestyles factors associated with health outcomes. There are numerous ways through which the environment can interact with other factors to create situations with varying effects on health. A cohort study in Japan found that vegetable dishes high in salt specific to mountain areas may cause a more severe form of stomach cancer [6]. In China, the northern mountains are areas of “undeveloped living conditions” with higher prevalence of H. pylori infection, leading to increased rates of upper gastro-intestinal cancer with rising altitudes [7].

Conclusions

This is the first assessment of cancer epidemiology ever conducted in a geographically/demographically specific area in Lebanon. Although the Baakline population is older than that of Lebanon as a whole, the cancer incidence rate is remarkably lower than the national figure. Further research may look at specific protective factors which make this population less vulnerable to cancer even as it grows older.

Our findings are an indication that serious efforts should be made to maintain the low contamination of the town’s

environment, and the healthy lifestyles which have served the population so well up till this survey. The decreasing fraction of Lebanese who maintain their permanent residence in traditional pristine mountainous areas such as Baakline should be encouraged by the evidence we present to know that they are less prone to cancer than the rest of the population.

Acknowledgements

Activities were hosted at the Baakline Municipality and the National Library of Baakline, our thanks to the Director and staff. Thanks also go to Dr Zaher Abu Shakra, qada physician, to Dr Fares Namour, head of the Health Committee at the Baakline Municipality, to Ms Raghida Timani, who coordinated the ladies of the Baakline neighbourhood committees in data collection, and to all the ladies in Baakline who devoted time and effort to data collection. Special thanks to Mr Moufid Seaid, who entered the data.

Funding: This project was made possible through a generous donation from H.E. Marwan Hamadeh, Member of Parliament.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- Cancer in Lebanon 2003–2004. Beirut, National Cancer Registry, Ministry of Public Health, 2008.

- National Cancer Institute. Risk factors and possible causes, 2013. Site www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk

- Factbook 2011: Lebanon. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 2011 (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/le.html, accessed 25 January 2013).

- Yaacoub N, Badre L. Statistics in focus, 2011. Issue 1: The labour market in Lebanon. Beirut, Central Agency for Statistics (in collaboration with the Ministry of Social Affairs), 2005 (http://www.cas.gov.lb/images/PDFs/SIF/CAS_Labour_Market_In_Lebanon_SIF1.pdf, accessed 12 February 2013).

- Igisinov S et al. Epidemiology of esophagus, lung and breast cancer in mountainous regions of Kyrgyz Republic. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2002, 3(1):73–76.

- Kurosawa M et al. Highly salted food and mountain herbs elevate the risk for stomach cancer death in a rural area of Japan. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2006, 21(11):1681–1686.

- Wen D et al. Helicobacter pylori infection may be implicated in the topography and geographical variation of upper gastrointestinal cancers in the Taihang Mountain high-risk areas in northern China. Helicobacter, 2010, 15(5):416–421.