Mogadishu, 21 September 2020— The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) are urging parents and caregivers in south and central parts of Somalia to ensure all children aged under five are vaccinated against polio during a special house-to-house immunization campaign, which began yesterday and runs until 23 September. Both agencies are advising health workers and caregivers to observe health and safety measures against COVID-19 during the four-day campaign.

This advice comes in the wake of efforts to curb the spread of the ongoing polio outbreak in the south and central parts of Somalia. The strain of polio that is in circulation is different from the wild poliovirus, recently declared as eradicated from Africa, but it can also put communities where not enough children have been vaccinated at risk and leave children paralyzed for life. The outbreak has paralyzed 19 children since late 2017.

“The only way to stop such outbreaks from vaccine-preventable diseases, including polio, is to vaccinate every child every time immunization services are offered, either through routine programmes or through such mass campaigns. We all have a moral responsibility to reach and boost the immunity of every last child in Somalia. Owing to access, security and health-seeking behaviour, we are missing a large number of children every year, who are not receiving these life-saving vaccines,” said Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative for Somalia.

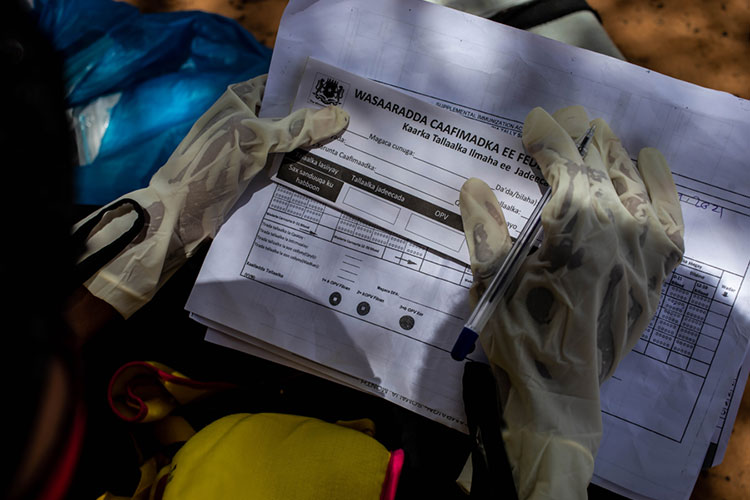

During the ongoing campaign, 6266 vaccinators in urban areas and 2685 vaccinators in rural areas will be going from door to door to vaccinate 1.65 million children aged under five with oral polio vaccine. In efforts to reach every child possible, an additional 1125 team supervisors will be visiting households in targeted areas. 3390 community mobilizers, sensitizing target communities, will play a key role in helping families to understand, trust and accept vaccines.

“It is critical that all routine immunizations continue, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Werner Schultink, UNICEF Representative for Somalia. “These vaccination drives will help prevent further outbreaks and will protect children from deadly diseases so they can survive and thrive.”

Before the campaign, polio health workers were trained and supplied with personal protective equipment, including face masks, soap and hand sanitizer, to keep them and communities safe from COVID-19.

This campaign is the first step in a two-part effort to raise immunity levels among Somali children. Somalia’s Government, WHO and UNICEF will conduct the second part of the campaign in October to continue to strengthen the immunity of Somali children. Parents and caregivers are encouraged to accept the vaccine when it is offered to give their children life-long protection against polio.

For additional information, please contact

Fouzia Bano

WHO Somalia Communications Officer

Email:

هذا البريد محمى من المتطفلين. تحتاج إلى تشغيل الجافا سكريبت لمشاهدته.

;

+252 619 235880

Eva Hinds

UNICEF Somalia Communication Manager

Email:

هذا البريد محمى من المتطفلين. تحتاج إلى تشغيل الجافا سكريبت لمشاهدته.

;

Tel: +252 613 642635

Notes to editors

There are multiple strains of polio, and there is a critical distinction between wild or naturally occurring poliovirus, which is today only found in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and the strain circulating in Somalia today.

In late August 2020, the world celebrated a historic moment: the end of wild poliovirus in Africa. This achievement still stands. There is no wild poliovirus on the African continent. But other strains of polio remain a threat as long as there are communities with low immunity levels.

The only way to eradicate all strains of polio is to vaccinate all children everywhere against polio. In places where polio transmission has long been stopped and immunity levels are high, inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) is used. In places at high risk of poliovirus circulation, and where immunity levels are not as high as they need to be, the best tool for the job is the oral polio vaccine (OPV), which is being used in this vaccination campaign.

This polio campaign is supported by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), an organization dedicated to the eradication of polio. Launched in 1988, the GPEI is spearheaded by national governments, the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and UNICEF, and supported by key partners including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance.

Even before 16 March 2020, when H.E. Fauziya Abikar Nur, the Federal Government’s Minister of Health, announced the first case of COVID-19 in the country, the United Nations agencies spearheaded by World Health Organization (WHO) provided substantial and timely support to the Federal Government of Somalia and its other Member States. This support allowed the country to prepare for what lay ahead. In February, public health measures for disease prevention, detection and response were significantly enhanced across the country. By early April, with support from WHO and other partners, the Ministry of Health had strengthened the capacity of 3 designated laboratories for COVID-19 testing. Since then, over 18 000 COVID-19 samples have been tested in these laboratories. WHO worked hand in hand with other United Nations agencies in the country, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and other national and international partners to improve preparedness, readiness and response to mitigate the early impact of COVID-19 outbreak.

Even before 16 March 2020, when H.E. Fauziya Abikar Nur, the Federal Government’s Minister of Health, announced the first case of COVID-19 in the country, the United Nations agencies spearheaded by World Health Organization (WHO) provided substantial and timely support to the Federal Government of Somalia and its other Member States. This support allowed the country to prepare for what lay ahead. In February, public health measures for disease prevention, detection and response were significantly enhanced across the country. By early April, with support from WHO and other partners, the Ministry of Health had strengthened the capacity of 3 designated laboratories for COVID-19 testing. Since then, over 18 000 COVID-19 samples have been tested in these laboratories. WHO worked hand in hand with other United Nations agencies in the country, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and other national and international partners to improve preparedness, readiness and response to mitigate the early impact of COVID-19 outbreak.

When he felt a little feverish during the second week of his new mission, Yare’s shoulders sank as he realized his fears may be turning into a reality. As soon as he felt a fever coming on, he rushed to the laboratory he was serving and asked his new friends to run a COVID-19 test on him. Within a few days, he received his results – his fear turned out to be true as he tested positive for COVID-19. In his heart, he wondered how his family would react.

When he felt a little feverish during the second week of his new mission, Yare’s shoulders sank as he realized his fears may be turning into a reality. As soon as he felt a fever coming on, he rushed to the laboratory he was serving and asked his new friends to run a COVID-19 test on him. Within a few days, he received his results – his fear turned out to be true as he tested positive for COVID-19. In his heart, he wondered how his family would react.