Around 20 million Afghans in 21 provinces are at risk of cutaneous leishmaniasis, a tropical disease transmitted by the bite of a sandfly. The disease may lead to open lesions and disfigurement, usually on the exposed areas of the body, and is associated with severe social stigma, especially for women and girls.

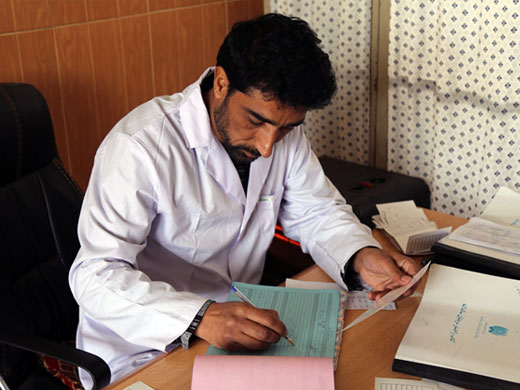

Through this photo story, see how WHO supports the fight against this neglected tropical disease in Afghanistan.

Photo credits: WHO Afghanistan/S.Ramo

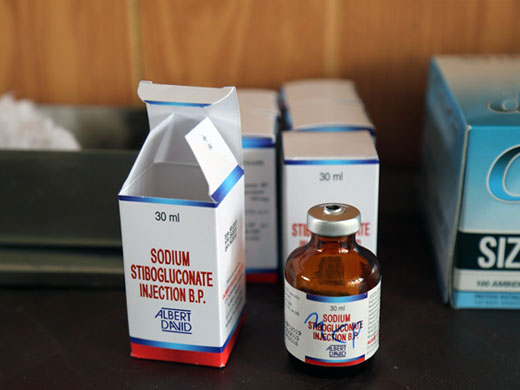

Parents of 5-month-old Maryam brought her to the WHO-supported leishmaniasis treatment centre at the National Malaria and Leishmaniasis Treatment Control Programme of the Ministry of Public Health in Afghanistan. Maryam had lesions on her face and arms, caused by the bite of a sandfly that spreads leishmaniasis. To cure her lesions, she received injections of sodium stibogluconate provided by WHO.